It’s hard to imagine now the pearl clutching that ensued when Rachel Cusk published A Life’s Work, her memoir about young motherhood, in 2001.1 In the last few years, there have been a slew of extremely good books, both fiction and non-fiction, on the tense triumvirate of marriage, motherhood and creative work. Splinters, All Fours, Soldier Sailor, Intimacies, to name just a few. There is without a doubt a publishing trend at play, albeit through a cishet lense.2

I gravitate towards these books like a moth to a flame. Even when the POV is different to my own - the parenting experience of one child, say, rather than multiple - there is an inevitable companionship. It was only when my husband said to me recently, “Isn’t this a bit of a busman’s holiday for you?” that I realised it might be time for me to flap my tired grey wings towards a new bulb. To re-route towards - I don’t know - historical fiction, for a bit. But before I do….

Elkin’s debut is not really about motherhood or marriage so much as it is about the idea of both, and how to maintain an intellectual life alongside a domestic one. Signed off work to process her recent miscarriage, with her husband David working abroad, Franco-American psychoanalyst Anna considers the shape of her solitude from her sofa in Paris.

“Right up until we left, our plan was for me to go with him [to London]… A real French psychoanalyst, they’ll love it, he said… In the end I couldn’t bring myself to go... Alone in the apartment is my preferred state. I can eat what I want, when I want. Watch what I want, while I eat what I want… [T]here’s something more physical about the aloneness, as well. I feel the space around me differently. It’s not that it’s quieter; it is a bodily experience of quiet. I am in the air differently.”

The book is split into three parts. In the first part (my favourite part) Anna is largely sedentary and observing, casting her mind from topic to topic: desire, fidelity, civic duty, motherhood, first love, urban life, France’s political situation, gentrification, Lacanian psychoanalysis and the renovation of her kitchen. The second part travels back to 1972 and tells the story of the unhappily married couple, Florence (who wants a baby) and Henry (who doesn’t want a baby - or a wife), who once lived in Anna’s flat. The third part sees Anna embark on an erotic journey (which she casts as a sort of ethical experiment) aided by her young, bohemian neighbour, Clémentine and to a secondary degree, Clémentine’s boyfriend, Jonathan.

I adore the title, which, like the book itself, has so many considered layers. Psychoanalysis is the intellectual scaffolding of the book, but there is also the literal scaffolding which Anna watches get put up and taken down from her apartment window as a way to track time passing. It also refers to the psychological scaffolding of our lives: the ways in which we build and break bonds. And lastly, it refers to the liminality of Anna’s physical and emotional state, where there is only so long she can afford to be off work, with her husband away, in order to engage in this sort of psychological flâneusery. (Fittingly, Elkin’s 2016 book, Flâneuse, is a feminist reclamation of the urban strolling woman.)

One of the biggest probes of the book is whether adultery can be ethical.

“Something about living ethically together is bound up in not judging our desires, or controlling and punishing them. But maybe that’s just me justifying [those choices].”

With Henry, it an selfish, often cruel motivating force. For Max Weisz, a Lacanian psychoanalyst (who published a book about sex and desire in the ‘80s that Anna is besotted with) and the father of Anna’s ex boyfriend, it is an intellectual choice. Incidentally, there is a lot about Lacan, which I enjoyed (whilst not always understanding) but it might be too much for some.

“Lacan liked to get a rise out of people, he was a showman. He meant they are constructions, that we can’t apprehend them directly, purely, except through the fog of language, even when we touch someone we desire, our desire is filtered through everything we have ever thought and heard and encountered, everything the culture has taught us about desire. Language isn’t innocent. The body isn’t innocent.”

For all it’s serious ideas, there are also very droll moments such as this conversation between Anna and her husband, which made me laugh because it’s exactly how I imagine French men would feel about British women.

“All the girls in London are vulgar, [David] says.

You used to say that about me. You thought I talked too loudly. American girls are vulgar, you said.

That was before I moved to London. I’ve spent entire Euro-star journeys listening to two girls talk about their spray-tans, best techniques, how long it lasts. The other day I was walking down the street and this woman was approaching with some impossibly small dog wearing a jacket on a leash and she calls out, BABE. Like bellows it. And some woman on the doorway several houses down goes, YES BABE. And the first one with the dog goes, YOU’RE NEVER GOING TO BELIEVE WHAT JUST HAPPENED. Like it’s totally normal to carry on a private conservation at top volume in the middle of the street.”

I bought the book after reading Deborah Levy’s blurb on the book jacket - “The Susan Sontag of her generation” - and pleasingly, it is as interesting as I hoped it would be: original, expansive and considered. (Elkin spent 17 years, on and off, writing it.) It is a book for book critics, an ‘ideas’ book which roams. The Guardian called it “an erudite novel with horny energy”, a description which took me right back to reading Milan Kundera3 for the first time aged 17, and discovering a whole new type of fiction.

It’s a book that doesn’t try and escape ennui, but go deeper into it. I found the ending a bit too neat and quiet and the character of Clémentine - a bisexual, bohemian artist’s model, who campaigns to end violence against women - wasn’t always entirely believable to me, but it’s otherwise worth every year Elkin spent writing it.

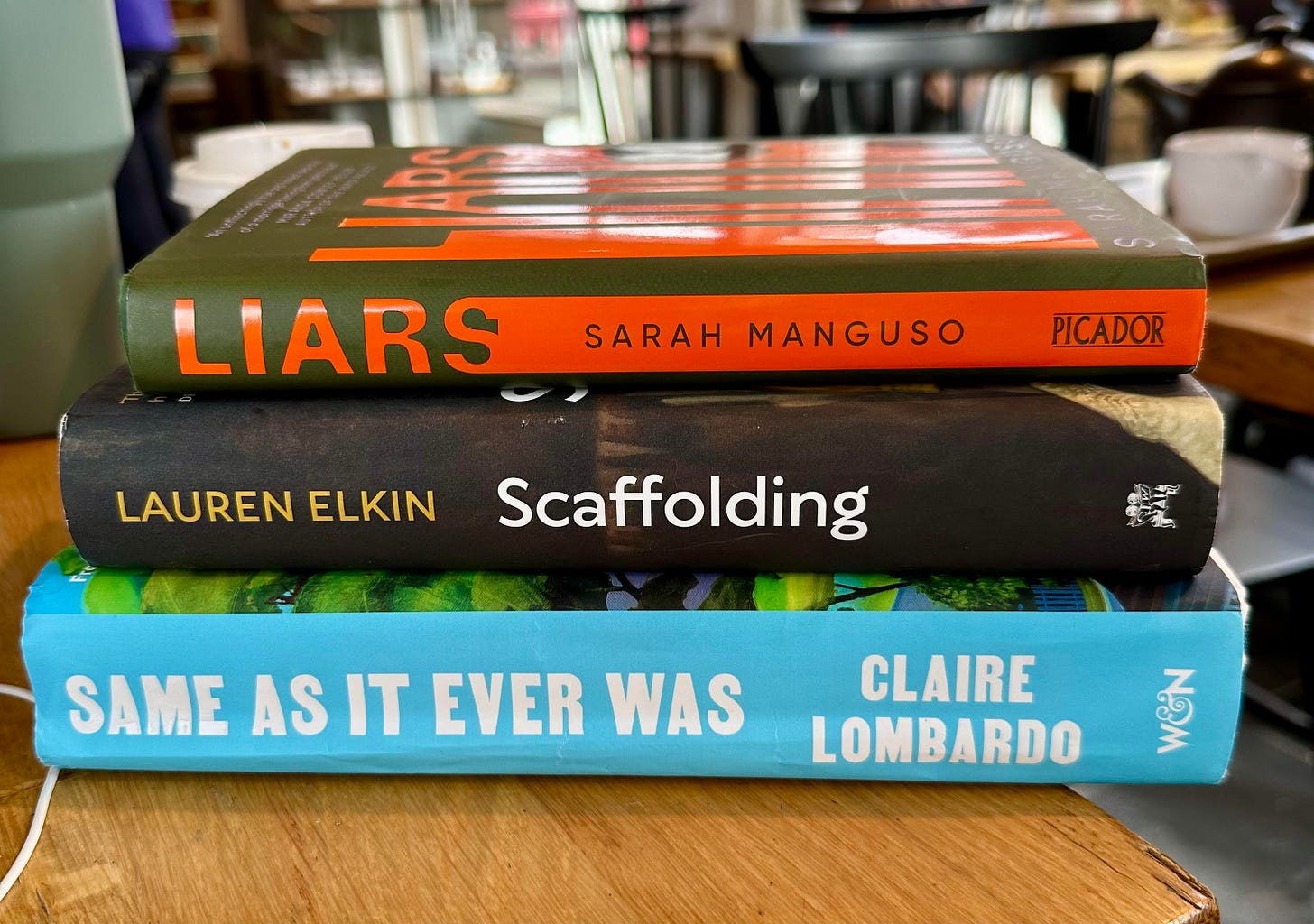

This is an interesting book to write about, because I found it a frustrating and increasingly tiring read, but I also haven’t stopped talking about it, and reading about it, which suggests that as a piece of art, it has succeeded. It has a huge number of high profile fans - Nick Hornby, Miranda Cowley Heller, Miranda July - and has already been New Yorkered, by Parul Seghal. It’s landed at a particularly prescient time, amid the orgiastic aftershocks of All Fours, when women are searching for more of the good stuff - and on paper (in July’s blurb, too) Liars looks to be the tonic.

Manguso’s ninth novel is about a writer, Jane, who is very briefly very happy with her filmmaking husband, John. Then they have a child together and Jane ends up doing all of the parenting, all of the domestic labour, is given no time to write and has to move 5 times in 7 years for John’s jobs. She is utterly miserable, but she won’t leave. Instead, one day, he does. And Jane, after almost a decade of feeling dismissed and diminished and ignored and taken advantage of, is not relieved, but furious. She is sick on rage, could burn a house down with rage, and her rage powers the book.

“It wasn’t that we’d been born angry; we’d become women and ended up angry… I pitied men for having to stay the same all their lives, for missing out on this consuming rage.”

The book is written in clear, staccato prose, which frequently read like diary entries, single sentences often forming entire paragraphs (I haven’t read any other Manguso, so I’m unsure if this is her usual style). Sometimes the starkness hits:

“I went to bed migrainous and leaking tears.”

“In the morning he wouldn’t speak to me. I felt like I would vomit.”

And sometimes it misses:

“Romance is nothing but a cheap craft-store decoration made to sanitize a desire to fuck.”

I assumed, vis a vis that line, that the title was referring to the lie of marriage - the broken promise - but in an interview, Manguso says:

“The biggest liar in the book is not John who's a cheater, or his affair partner. It's Jane who's a victim of her own self deception….For Jane, it doesn't really until she's pregnant, and then she realizes that she has been sort of just morphed- by the force of John's ego and his ham-handed gaslighting, she's been converted from a woman artist to a mediocre man's bang maid.”

Liars is a work of auto-fiction, meaning that it was inspired by Manguso’s life, and she has said that Jane is much angrier than she was when her own husband cheated on her and left her, as angry as she wished she had been. But this rage feels oddly circulatory: it is not galvanizing, but stultifying. Once John has left Jane (this isn’t a spoiler btw, it’s on the book jacket) you hope to see her spread her wings, to liberate herself, emotionally, erotically, artistically - finally, she’s got rid of that jerk! - but she just carries on cleaning her kitchen and furiously looking back.

In Jane’s telling, John is an unequivocally shit person, leaving her to solo parent for entire weekends to go work in his studio, only texting her to tell her that he has diarrhea.

“John came home and I couldn’t believe how lucky I was to have such a happy family. It wasn’t happiness; it was the temporary cessation of pain,.”

It would be dangerous (farcical, even) to suggest that all women, all mothers, are fulfilled - in their marriages, with their domestic load - but suggesting that every woman is coerced into marriage (it is destined “from the cradle” and “every married woman I knew felt the same”) and that every heterosexual marriage is abusive, feels like an odd over-corrective, as well as out of date. I’m currently reading Ursula Parrott’s 1924 novel, Ex-Wife, which has just been reissued by Faber and at times, it feels more modern than Liars - a book written 100 years later.

But - and this is a big but - Jane is allowed to overcorrect as much as anyone is allowed anything in fiction. As Sara Petersen points out, this isn’t John’s story. There are plenty of books which show both sides of a marital breakdown - The Divorce, Fates and Furies and of course, Fleishman - but this isn’t the one. This is Jane’s One Thing. John took everything else from her, he isn’t going to have her book goddamit! This is a feminist point, that the book is entirely hers, after years of being denied her own creative life. As is the laundry list-like element of it, which is that the life that Jane has found herself in is relentless, that this life she has been forced into by John is relentless. I knew that while reading it, and I still found the relentlessness, well, relentless.

It’s an interesting piece of work to consider alongside All Fours - the imagination and creative expansion and compassion of a break-up, versus thid static, crouched ball of fury - for the difference in financial circs: in July’s novel, both artists are allowed to work, both have their own studios, there is money to travel and think and re-decorate entire hotel rooms just for the hell of it. In Manguso’s, there is endless cleaning to be done and no money or time to write. (In both, incidentally, the child is never the problem - something I think often gets flattened/ misunderstood in works which criticise the cultural construct of motherhood. “[The child] is the engine by which I learn what is left of my life” says Jane movingly, at one point.)

Another thing which really made me re-think my, er, thinkings, was something Manguso said in an interview, which is that she doesn’t make a habit of reading her Goodreads reviews, but that she did on this occasion and:

“It is in equal parts some of the greatest validation I’ve ever received and the most terrifying cultural report I’ve ever read. It’s incredibly disturbing that hundreds of people, in the first week of publication, have said of this domestic abuse novel: “This is exactly what all women have to deal with, thank you.”

If this book is a cultural report, then it is a book calling for a revolution - for the end of cishet marriage. I’m really interested to know what Manguso would build in its place. Liars does not tell us - but perhaps her next book will.

Same As It Ever Was by Claire Lombardo

In Lombardo’s second novel (her debut was the hugely successful and similarly long-titled The Most Fun We’ve Ever Had), fifty-something Julia, a mostly content wife and mother to two grown children, reflects on a period of depression two decades earlier, as a lonely mother of a toddler, and her friendship with an older woman, Helen. Their friendship precipitates a terrible chapter in Julia’s marriage - and as a result, her husband asks her to never speak to Helen again. And then two decades later, Julia bumps into Helen, by chance, in the supermarket.

Julia is a different woman to the one Helen once knew - but their encounter unmoors her and unravels decades of memories, back to the day she met Helen in a botanical garden, but also further back into her past and a sad, complex childhood. When she bumps into Helen, Julia is not experiencing a mid-life crisis, as much as she is having a small crisis of faith: her son, Ben, has just told her that he is marrying his pregnant, university girlfriend, whose ubiquitous happiness (her name is Sunny, for godsake) makes a naturally cynical Julia mistrustful; her teenage daughter, Alma, has morphed into a furious person, whom Julia is mostly nervous around.

Like Tom Lake, this is a novel about looking back, in order to look forward and also like Tom Lake, this covers small children, teenage children, adult children and before children. Unlike the gentle Tom Lake, the emotional stakes feel much higher. Julia is the Julia she is now, because of the Julia she was then. And sure, we all are to an extent, but past Julia is so close to the surface of current Julia - and the spectre of her past self, in full disarray, still haunts her.

Same As… reminded me a lot of Meg Mason’s first novel You Be Mother which I found heart-breaking in its depiction of loneliness. Young Brit, Abi, moves to Australia to be with the useless father of her baby. Desperately lonely and broke, she seeks solace in an intense friendship with her older, wealthy neighbour, Phyllida. As in Lombardo’s novel, a surrogate mother-daughter relationship goes abruptly and horribly wrong.

Lombardo is particularly good at drawing character (“Brady in totality, the pinnacle of performative wealth and the overly texturised haircut Alma calls a bro-flow”) and relationships with emotional complexity. Julia’s husband Mark is not an absent, distracted partner and father - he is kind, straight forward, supportive - and it is she, not him, who is emotionally absent. I think of something he says to Julia, frequently.

“You aren’t engaging. You’re doing the thing where you’re just - marinating in things.”

Lombardo writes movingly on the contradictory loneliness of early motherhood - a “persistent cruelty, a constant, simultaneous desire to be together and apart” - and how easily it can tip into a sort of martyrdom. Julia is “so lonely it had started to feel like a corporeal affliction” and yet, as she notes haughtily to Mark, “I would rather die than join a book club”.

Another strength of the book is the exploration of teenage girlhood, which is was grateful for, as most of the books I read on the toll of parenting focus on younger children.

““May I be excused?” Alma asks, appearing at her elbow with all the prim obsequiousness of a Dickensian governess. “I have to go study.” She meets Julia’s eyes fully, a challenge, because it’s a Saturday and she’s a second-semester senior.

“Sure,” Julia says, because she is afraid of Alma.”

The biggest strength of the book, however, is Julia: a main character who holds in her the the full spectrum of ambivalence that so many women feel around marriage and parenting. She both craves and resents domesticity. As a young woman, she longs for a stable, safe life with Mark - while despising herself for being so bourgeois.

“It was less that she’d never been comfortable in the company of women than she’d never been specifically comfortable in the social company of anyone [and] there was something about the moneyed, fine-tuned firing squad of preschool moms that set her particularly on edge.”

In Same As… Lombardo has written another moving, compelling, emotionally textured book, which occasionally tips into earnestness. Like Meg Wolitzer (and Franzen, if Franzen wrote about women a little better) she writes so beautifully on the intricacies of family dynamics, the shifting nature of maternal identity and the blows it must withstand. If you’ve read it, or any of these books, I’d love to know your thoughts.

I think it’s extremely good, I read it every time I have a baby

I think part of this is that queer families are typically freed of a certain heteronormative expectations of marriage and parenthood which fuel these books, but I’d still love to read more books about the tension of parenthood and creative work in non-hetero couples

Not a perfect artist, still an interesting novelist!

Adding to my goodreads list!

Popping in to point you in the direction of “Rapture” by Emily Maguire if historical fiction is next on your list x