The tie that binds this trio of debuts is the fragility of identity: in the heart-shattering The Names, Florence Knapp shows how an entire life can be determined by the name given to a baby; in the bittersweet and poetic A Room Above a Shop, Anthony Shapland explores forbidden love during the AIDS crisis; and in Adelaide Faith’s charming and quirky Happiness Forever, a young woman learns to live—and love—in her own skin.

Happiness Forever (out 8th May) is about a veterinary nurse called Sylvie who is in love with her therapist. Before Sylvie started seeing her, she was struggling to find joy and meaning in the world—to see herself as a real person in it—beyond her brain-damaged dog, Curtains. With the therapist’s help, and her new friend Chloe, life is beginning to look more vivid for Sylvie—even if she thinks about the therapist all day, every day, and outsources her entire reason for being to this woman.

“[Sylvie] felt she might be saved if she followed the therapist, got her approval, made her love her. There was a sense that a great freedom was close. There might be no need to worry about carrying on when somebody else had already worked out the meaning of life, if the meaning of life was how to become the perfect human. The game, the puzzle might be over. Whatever it was the key to, the image made Sylvie feel sharp and happy and insanely high.”

And then her therapist tells her she’s closing her practice and Sylvie feels the aching void opening back up to swallow her. How can she continue trying to be present in her life, without seeing her therapist each week? And if the therapist wouldn’t consider being with her romantically… would she consider adopting her?

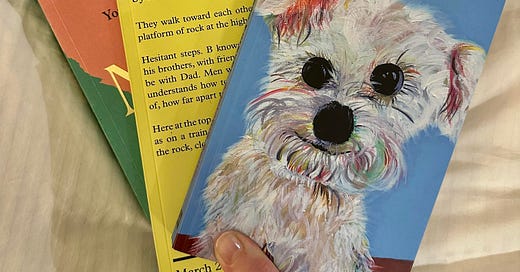

It’s funny and tender and adorable, right down to its cover, with its scrubby little portrait of Curtains, with his inquisitive little face and wonky eyes. On the surface it’s a book about emotional transference—Sylvie thinks she wants to be with or just be her therapist—but really, it’s about yearning for actuality. (My favourite kind of book.) To feel like you are a person who is present, rather than a shadow; someone who is intact, rather than 48,000 pieces of person floating around the ether: an eye, a leg, a fingernail. Which, incidentally, is how I feel most days: like I am made up of millions of bits of ephemeral matter, floating beyond my reach, so that I can never quite gather it all up to stuff back inside my meat jacket. (Therapise that.)

What I really love about this book is that things are kept a little ambiguous. We know that Sylvie used to drink, we know that she messed up a relationship with someone she really loved, and we know that people used to call her ‘crazy’, but we don’t know bad any of it got. Was it that she was mentally unwell, or was it that she just felt like “a freak”, which most of us do sometimes. But what Faith emphasises is that it’s not important whether it was something everyone thought, or something just Sylvie thought about herself, than it is that she feels it at all.

When Sylvie is trying to explain to Chloe—slightly more worldly, but also gentle and thoughtful, as everyone in this book is—what makes her therapist so disarming, she explains that “she’s made a huge success of being a person.” Sylvie explains further: that her life is small, but that the therapists’s seems big. But “small can feel good and real” reminds Chloe. “And there’s less compromise with small. You can be more free.” Such observations are small and necessarily simple, which is what makes them so sweet and so true. Chloe helps Sylvie realise that her job at a vet’s, is “a choice of where she wants to be as a human, with values of focus and honestly, she likes how it feels”.

I think and write a lot about how confusing it is to find your identity in the chaos era of contemporary life—to feel like you’ve made a meaningful choice, or forged an interesting life for yourself—and this novel reads like a meditative balm. I have been seeking a smaller life for some years now. Less time online, more time at home, or just face in a book on a park bench without a phone. Quietly, deliberately, with tenderness and never force, Happiness Forever reminds us that the most meaningful choices can be the small, everyday things that simply string a life together.

There’s nominative determinism—the idea that a name can shape your career: a meteorologist called Sarah Blizzard; a runner named Usain Bolt—and then there’s dictating the course of your entire life. That’s the plot of The Names (out 8th May), Florence Knapp’s moving debut novel, where a little boy is named Bear in one life, Julian in another and Gordon in a third. His name determines three completely different lives, for three very different men.

The Names begins in 1987 (the year I was born, incidentally), when a woman named Cora, who lives with her 9-year-old daughter Maia and her abusive husband, Gordon, gives birth to a young son. Her husband has told her she must register his birth and that he must be called Gordon. Cora doesn’t like the name Gordon—nor that to yoke her baby son to his father’s name is to yoke him to a legacy of abuse—but she knows that to resist naming him after his son, could see her killed. So in this first version, he is named Gordon. In the second version, she calls him what she has always wanted to: Julian. And in the third, she lets her daughter—sweet, perceptive Cora, who can sense the danger in the house, even if she never sees it—name the baby, Bear.

Bear grows up to be a gentle wanderer, who travels the globe while his patient childhood girlfriend, Lily, waits at home. Julian is artistic, avoidant, a designer of silver jewellery, yearning for an artist named Orla who works nearby. And Gordon grows up to be bullish and brash, as dismissive of his mother as the Gordon before him. The book is not just about these three men, but the family around them who are also different in each possible life. Long-suffering Cora, sweet, traumatised older sister Maia, their kindly grandmother in Ireland worrying for the daughter she never sees, the grandparents who made a son in their own image, a Gordon, who, just like his father, is a shattering life force against whom nothing can ever be spoken.

Because Gordon is a trusted GP, and who wouldn’t believe a hard-working, reputable GP over a woman who never leaves the house? Like Nesting, this is a thought-provoking exploration of how domestic abuse thrives on isolation and misogyny; about who is believed (pillars of the community) and who is not (stay-at-home mothers, shy friendless mothers, mothers with ‘issues’—‘sensitive’, ‘unstable’, ‘depressed’—as described by their devoted husbands.) The depiction of physical abuse, manipulation, coercion and gaslighting is devastating and subtle.

Similarly affecting is the idea of nature vs. nurture. Cora wonders if her son will be like her husband because he shares his genes; or will he be like his father because his father crafts him to be so? The parts where Gordon has learned to dismiss his mother—to laugh at her stupidity, her shyness, her cooking—as a survival technique, is a unique insight into how abusive men are created. (It made me think a little, too, of Adolescence. Of violence learned.)

When I first picked up The Names, I wondered if I might find it a bit sentimental. It occasionally strays into that territory but for the most part, it’s a sucker punch of a novel that I think will be one of the biggest books of the year. (No doubt the publishers think so too: it is being published in 20 languages, which is extremely rare for a debut.) And my god, did it make me weep. At one point, I stuffed a fist into my mouth, to silence a howl.

This is a book about how a choice—any choice—cannot guarantee safety, or happiness. Calling her baby son Gordon doesn’t keep Cora and her daughter safe; it just allows fate to shape their lives in different ways. Cora might escape her abusive husband in one life, only for another tragedy to smite her. Or she might stay with him, imprisoned in her home without a phone or a car or a bank account, until one day, expected salvation. As Cora’s best friend Mehri says to her (in one life):

“You are not responsible for the goings-on of the entire world. Yes, people’s lives bump and collide and we send one another spinning off in different directions. But that’s life. It’s not unique to you. We each make our own choices.”

Life is full of cruelty, and serendipity. The Names explores this with great aplomb.

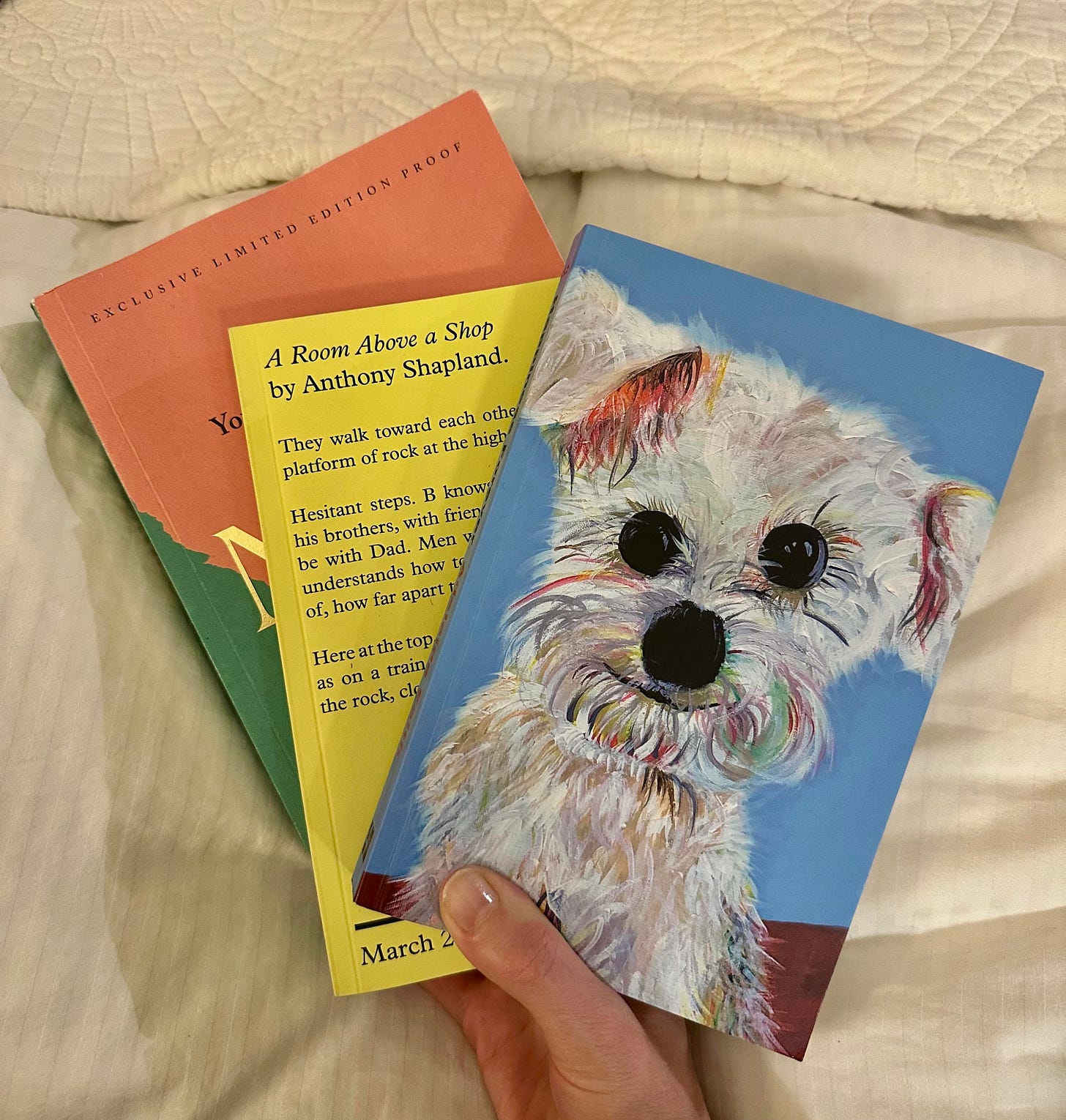

Anthony Shapland’s debut, A Room Above a Shop (out now), is another one to snap your heart strings. A bittersweet, spare, poetic novella about the secret relationship between two gay men in the Welsh Valleys in the late 80s—set against the harrowing backdrop of Section 28 and the AIDS crisis—it is a novel with little dialogue and minimal plot, about what is unsaid and unseen, by all but two.

B and M meet in a pub one Christmas. They are familiar to one another, as those in small towns usually are, but they have never spoken. M (only their initials are used, a neat way of emphasising the need to hide your true identity) is older by 15 years—a gentle, affable bearish figure who runs the local ironmonger; B is a young decorator, dreaming of becoming a painter. One of the most poignant moments in the book is when the pair have arranged to meet up for the first time after the boozy evening in the pub.

“Hesitant steps. B knows how to be with his brothers, with friends, how he used to be with Dad. Men with men, mates.”

But with M, it is a different story. Showing their true selves to each other is a slow process, after a lifetime of hiding, masking, shutting parts of themselves off.

“[B] watched how the others were and he made his body move the same, he blended in. He felt like he was a pilot of something he didn’t know how to steer… He monitored himself all the time. He was exhausted, spoke even less. Whenever he heard himself out loud he felt like he was going to slip, so his accent mimicked their accent and slowly his voice disappeared. He was hidden and safe. He failed, fell further behind. He let conversation peter out until he was completely alone.”

The only way a relationship between the two of them could work is if they live together, as colleagues. So B moves into M’s shop as his ‘apprentice’, lodging (they will make sure to tell people) in the small spare room, which is barely an annexe with a camp bed. And in this shabby room above a shop unfurls a story of private commune, of quiet and gentle intimacy, so precious for its lack of artifice: just a mattress on the floor, from where they watch the light and dust dance across the room. They eat slowly, dress slowly, watch each other slowly. They hardly talk during the day, daren’t even catch each others eyes, making their evenings together upstairs all the more meaningful and passionate. The stakes are not just high, they are impossible.

“Exposed, they would be shamed. Shamed in the town that knows their fathers and their mothers, their brothers and sisters and their pets, and all the stories, lies and missteps they have ever taken as children, as boys, as men.”

At the end of the 1980s, the valleys were in a period of brutal social change, thanks to the decline of the coal mining industries, with unprecedented levels of unemployment and poverty. M wryly notes how many of his customers, who would shun him in an instant if they knew he was gay, had not been able to pay their bills, his counter littered with IOUs. Shapland dedicates much time to vividly drawing the beauty of the valleys, which also host the “strife [, t]he anger [and] divisions” of deundustrialistion.

“Houses fall apart, worthless. A place of industry, now sagging, underfed, starved of purpose. Drainage ditches choke with briars that scratch across the pasture. Flag iris fan, winter-dry and brown where reeds clump. Marginals thrive in the lost farm’s soggy decline and grass cedes to scrub, white with hoar.”

I told you it was poetic.

Last week, I recommended an interview that I loved with Claire Keegan, in the current issue of The Gentlewoman. Keegan tells Seb Emina that the people whose stories she is interested in telling, are the people who don’t want to talk. How do you tell their story of people who won’t talk? You find new ways of storytelling. I thought of this again and again, while reading A Room Above a Shop. No-one will ever know of B and M’s relationship, but them. When they are both gone, it will be like it never happened. Knowing this is both bliss, and torment.

I think there may be few things more exciting than seeing your own novel pop up in a newsletter you love and would be reading anyway! Thank you so much for including The Names here with this lovely review (and delighted to be alongside two books I'm so keen to read myself). x

The cover of happiness forever is just too sweet to resist buying - consider me sold