I was reading Danielle Steele before I was reading Harry Potter and so I’ve always been ambivalent about the ‘young adult’ (YA) genre - which, depending on who you ask, refers to readers who are 12-18, or 14-18 years old. I’ve never put stock, I guess, in the idea that teenagers want to read books that are not quite adult.

I’ve recently come to think that YA is actually a useful tag for adults, denoting comfort in much the same way teen dramas like Gossip Girl and The Gilmore Girls can offer the adult viewer a nostalgic cosiness, a chance, perhaps for a do-over of our teenage years. Indeed, Meg Rosoff, who wrote (the very good YA novel) The Great Godden, once said that 55% of YA books were bought by adults. The phenomenally successful Matt Haig suggests that YA is a useful tag not just for the reader but for the author, "blurring the boundaries" of genre in a way that more rigid adult fiction categories do not allow so easily (the market divides books into literary, commercial, speculative fiction etc - a faulty system to be sure but one that I sense is changing).

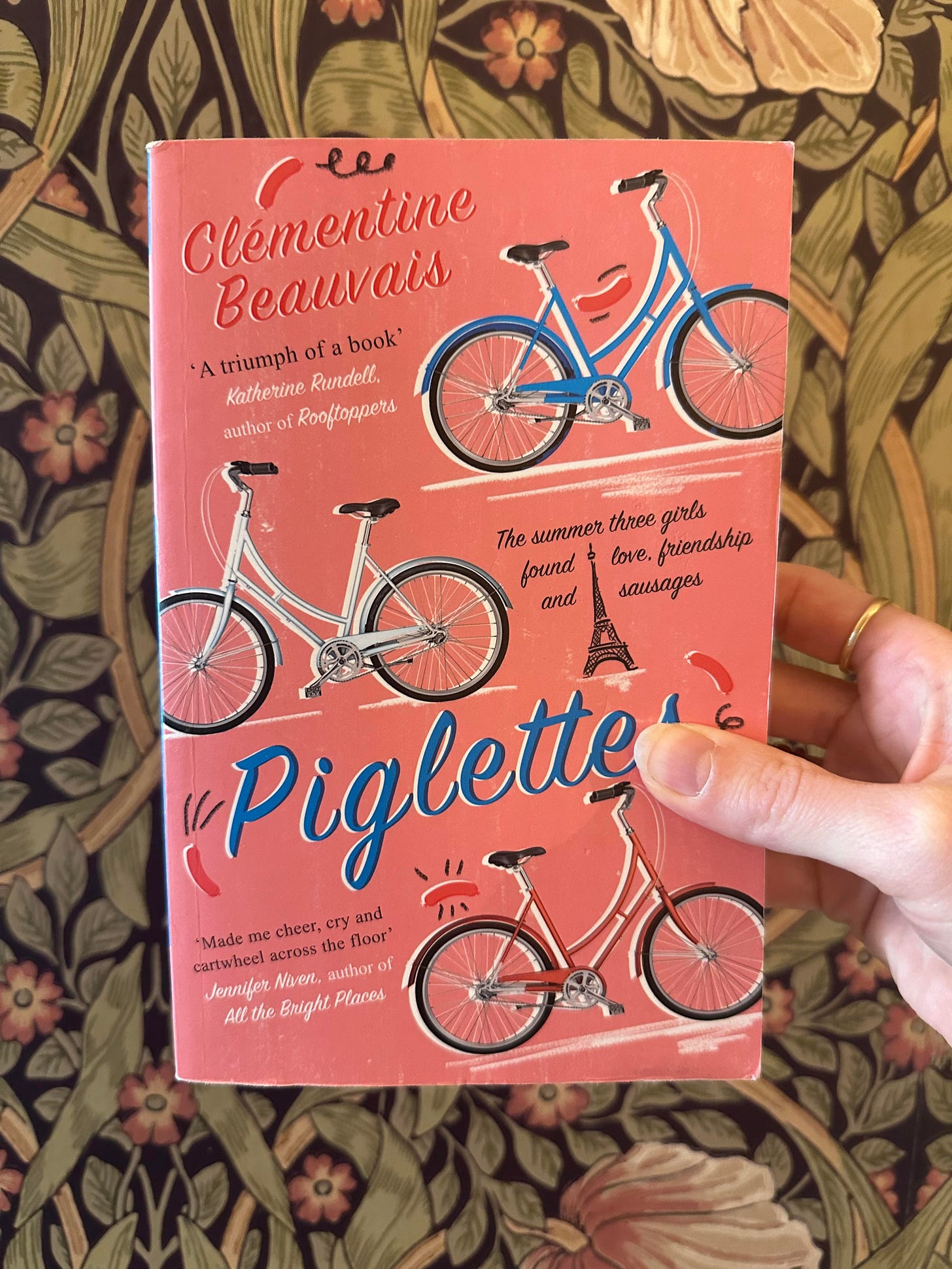

The cover of Piglettes, a 2017 French YA novel translated into English by its own author, Clémentine Beauvais, is very much aimed at the teenage girl. It’s candy pink, with “the summer three girls found love, friendship and sausages” scrawled across it. I probably wouldn’t have picked it up, had I not seen a post on Instagram from Katherine Rundell, whose latest fantasy book for kids Impossible Creatures I’m currently reading with my daughter, whose book The Golden Mole is one of my absolute favourites to gift, and whose opinion I trust implicitly. I bought it immediately, read it in a gasp of delight, and now want to give it to everyone I know, teenage or otherwise. The lesson: never judge a book by its cover - or by its genre!

Piglettes is about three teenage girls living in Bourg-en-Bresse, who have been voted the three ugliest ‘pigs’ in their school on Facebook. For 15-year-old Mireille, this is nothing new - in fact, she can’t believe she’s won bronze this year, instead of gold like usual - but her fellow winners of The Pig Pageant, Hakima, 13, and Astrid, 17, are upset and mortified. Mireille has never met them - they’re 2 years younger, and 2 years older, light years for a teenager - but she decides that it is her job to lift their spirits.

“You’re funny”, says Astrid thoughtfully.

Since I’m not just funny but also generous, I give her some Fanta. Then a bit of leftover cooked ham. Then a slice of home-made tiramisu - I tell her I made it myself with my little hands; she says I’m a good cook.

“It’s because my grandparents have a restaurant. I fell into it when I was a child, like Obelix. Which might explain the comparable BMI.”

“I’m not a good cook,” says Astrid, “but I make a good apple purée.”

Then, “How do you deal with it, winning the Pig Pageant at Marie Darrieussecq? It’s hard…. it’s really hard, seriously.”

“Oh, I’m amazingly good at not taking things seriously. I know that my life will be much better when I’m twenty-five; in the meantime, I can wait. I have a lot of patience.”

Mireille knows that the best way to exact revenge on the vile Malo (her ex-best friend, who runs the pageant), is to turn the award into something positive. And so our irrepressible protagonist rebrands the three of them ‘the piglettes’ and masterminds a 367km road-trip to Paris, by bicycle, over the course of a week. They will fund their journey by selling sausages (naturally) and they will arrive on Bastille Day, chaperoned by Hakima’s grown-up brother, Kader. Who wants to be beautiful, decides Mireille, when you can be resourceful and newsworthy?

The piglettes all have their own secret reason for why they wish to arrive in Paris on the day of the official Bastille celebrations. Mireille wants to confront the French president’s husband, a philosopher whom she knows to be her secret father. Hakima wants to confront the general she holds responsible for Kader losing his legs during the war. Astrid - and I love this detail, it’s so specific and random - wants to meet the rock band, Indochine, who are playing at the celebrations and with whom she is absolutely obsessed.

The book is such a lovely riposte to online bullying - with Mireille coaxing the girls into a place of acceptance and resilience - but it’s also incredibly funny, particularly the way in which Mireille winds up her mother. Mireille is irreverent, imaginative, optimistic and relentless - she reminds me of an older Eloise at the plaza - and she absolutely exhausts her elegant, rather dry mother to repeated comic effect.

Mireille, we saw you on TV. Answer my texts more than once a day, please. I hope you didn’t drink any Sancerre? Call me back. Mum.

Mummy darling whom I will love eternally and for ever, I promise I didn’t drink any sincere. Yours Sancerrely xxx

There’s also a lovely secondary storyline about stepparents and how hard it can be for a child to trust you. Mireille has no time for her long-suffering stepfather, Philippe, who has been in her life since she was a small child and with whom her mother is now expecting a baby. But over the course of the novel, Mireille begins to realise that he genuinely cares about her and how dismissive she has been of that kindness. It’s a lovely small moment and one to be valued as much as the bigger, funnier ones.

Piglettes is easy to read and frequently silly - but it’s also very clever. It should be used a handbook on how to approach Big Topics with teenagers and pre-teens, in a way that does not patronise or intimidate or humiliate. Through the pageant, the book explores Western culture’s narrow beauty ideals, fatphobia, misogyny and online bullying, but it also explores racism (with Hakima and Kader somehow ‘unable’ to sell as many sausages as the other two), the trauma of war and the discombobulation of becoming disabled in adult life (through former soldier, Kader, whom a besotted Mireille refers to hilariously as ‘The Sun’) and the complexity of the Nazi occupation in France (through an old lady, Adrienne, who the piglettes meet en route and who was forced to abandon her village in the 1940s).

“Marguerite fell in love with a man in our village. She met with him almost every day in the woods and the countryside. They were, er- good friends.”

“Was he in the Resistance or was he a collaborator?” Hakima asks.

“Hakima!” The Sun grumbles.

“Neither,” the old lady whispers.

“Not everyone was in the Resistance or a collaborator,” Astrid explains in a teacher’s voice. “It’s a highly simplfied vision of what happened in France during the Second World War.”

“But they told us at school…”

“That’s because you’re young. They put it like that so you wouldn’t get confused. But when you get to our age, you’ll do the Second World War in History again and you’ll see it’s much more complicated than that. That’s what Madame Adrienne means: he was neither resisting nor collaborating; he was keeping himself alive, that’s all.”

It also considers parental absence (Mireille is the product of an affair), the power of sport to improve mental health (not to lose weight), female friendship and quite honestly, everything you could possibly find for a teenage girl to think about and worry about. Hakima even gets her period for the first time, while they are on the bicycle trip. And yet there is nothing tickboxery about it. Everything feels like a seamless part of the plot and it clips along beautifully. There’s also a really lovely bit on schoolgirl crushes.

“We cycle off, and my heart is a little bit like one of those moronic moths that knocks themselves out on garden lamps. Kader’s a light inside a globe, and me, I’m fluttering around it, going bump, bump, bump, against the glassy shell.”

At 26, Kader is not unaware of Mireille’s adoration for him and yet he deals with it graciously, gently setting unspoken but clear boundaries. Mireille never thinks anything is going to happen between her and Kader (she feels safe in her fantasy), and Kader never allows Mireille to feel embarrassed. There’s also a somewhat hopeful exploration of a relationship between a teenage girl and an adult man. Why can’t they learn from each other, suggest Beauvais; does there always have to be something dubious about a 15 year old and a 26 year old enjoying one another’s company? This book emphatically suggests not.

The thing I love most about Piglettes is not that Mireille never falters in her confidence and her quest - sometimes she allows herself to be sad, she is not always the self-described “lotus leaf”, from whose back the water runs straight off - nor that the plot is always believable (it’s frequently nuts), but that it’s not any kind of revenge narrative. Malo does not get his comeuppance, at least not in any public way. The girls do not have a Princess Diaries-style makeover. Instead, it’s a lesson in how to spin shit into gold. How to take the worst things someone can say to you, and walk away with your head held high, your self-worth intact, whilst not changing a single thing about yourself.

Reading it makes you think anything is possible, if you could employ one tenth of Mireille’s optimism and resourcefulness. If I was a teenager, it would make me realise how powerful I could be. I’m 37-years-old and I came away galvanised, hopeful, inspired.

Piglettes is an utter joy, from start to finish - I hope it becomes a modern classic.🐷

The way I toggle back and forth from your newsletter to the library app! (This is not new news but anyway). All three books reserved - Piglette for me and the children’s books for me and my son. Thanks always, I bloody LOVE your reccos so much and reading this newsletter is like getting an email from a well-read friend. Have a beautiful week Pandora and everyone! 💛

So, so delighted to see some love for this brilliant and very underrated book!