On smartphones, teenagers and anxiety

An interview with Jonathan Haidt about The Anxious Generation. Plus a grab bag of culchy recs

Hello hi happy Saturday!

This week I am delighting in Compeed’s genius anti-blister stick, an insane malteaser traybake, and this meme, via Nick Hornby, which ruined me for an entire work day:

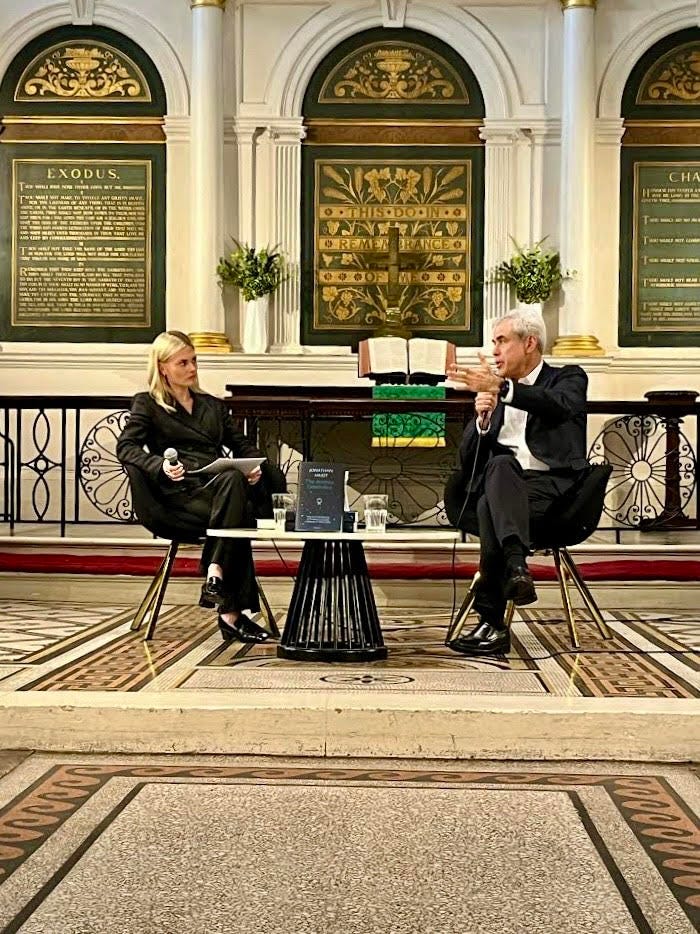

I was hoping to share a podcast recording of my interview with Jonathan Haidt for How To Academy on Tuesday night about his new book, The Anxious Generation: How The Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, but gallingly the audio corrupted! So here’s a precis of sorts, on the book (a Sunday Times and New York Times bestseller), my thoughts, the experts countering it and Haidt’s response to them in our interview.

Haidt is a social psychologist and professor at NYU’s Stern business school, who became absorbed in the sharp uptick in anxiety, depression and self-harm in teens in the UK and US between 2010 and 2015. The only reason he could find for the enormous uptick in that specific time period (in that, he says, things like academic pressure and cost of living crises and world wars etc have always existed) was the mass adoption of iPhones by teens and the arrival of a front-facing camera.

The statistics are horrifying. Between 2010 and 2015, suicide rates in 10 to 14-year-old girls increased by 167% and in boys, 92%. Nearly 40% of teenage girls who spend over 5 hours a day on social media have been diagnosed with depression. A 2015 survey from The Pew Research revealed that 1 in 4 teens are online almost constantly. (When they aren’t actually using their phone, explains Haidt, they are thinking about it, in their pocket.) By 2022, that had risen to 46%. The age at which kids are getting smartphones is getting lower and lower, with kids as young as 5 now owning one. And whilst social media companies are meant to not allow kids to sign up until they are 13, they deliberately don’t really enforce it, so that most kids now have social media apps well before the age of 10.

Teachers are desperate - they can’t get the kids off phones long enough to concentrate. Parents are terrified - what should they be doing? What can they be doing? It’s unsurprising his book has touched a nerve.

The Anxious Generation calls for four things:

no smartphones before 14

no social media before 16

phone-free schools

a return to play-based childhood

Haidt’s argument for this is both cognitive and social. Firstly, the brain’s frontal cortex is not fully developed until your early 20s and is considerably more developed at 16, than it is at 10. The frontal cortex is what allows you to make decisions, to deal with discomfort, to resist temptation etc. Secondly, he argues that kids are growing up in defend rather than discover mode, because they aren’t having enough offline experience. It is leaving them ill-equipped to deal with the adult world (which is a bit of an extension of his previous book, which looked at ‘safetyism’). Thirdly, they are unable to concentrate for more than a few seconds, or get into a state of flow (vital for good work and for general well-being) because they are always checking their notifications.

And to clarify, because I’ve seen a lot of people railing against this, who haven’t read the book: Haidt isn’t arguing that teenagers shouldn’t use the internet, he’s arguing against them having the internet in their pocket 24/7.

In an episode of You’re Wrong About, featuring one of Haidt’s biggest critics, The Washington Post’s Taylor Lorenz, host Sarah Marshall dwells on her own feelings around her iPhone (they don’t really talk about the adolescent brain, which is really the point of Haidt’s work.) She says that she has a lot of anxiety around her phone, which I am sure lots of you might also have.

I have always found my phone extremely anxiety-generating. I don’t hate my phone, I find it fun a lot of the time (animal memes!!) and clearly very useful, but as someone with intense sensory overwhelm, who gets very over-stimulated by life generally, my phone is something I have always had to limit. People used to tell me I must be extremely disciplined (or they assumed I was simply sanctimonious) rather than realising not keeping social media apps on my phone wasn’t about deprivation, as much I was trying to prevent my brain catching on fire.

I don’t want my kids to have the anxiety around their phone that I have, and I am an adult whose frontal lobe has all its executive functioning (one would hope) in place. I have always been a big fan of what my brother has done with his teenagers and their smartphones, which is to make all their apps disappear after they have used up their social media ‘minutes’ each day. (He is very techy, so he had a jump on this.) As a result, my 14 and 18 year old nieces have absolutely no anxiety around their phones and would have no problem putting them away in their bag for prolonged periods of time. I know that this is a rare and I know that many parents don’t have the time, or the energy, or the tech knowledge, to enforce this.

One of the most interesting areas of the book is that smartphones and social media hurts teenage girls a lot more than it does boys. Girls are culturally coded to be much more visual than boys, and the volume of images - airbrushed faces, unhealthily thin bodies - via social media (hundreds more than I was ever subjected to via Heat magazine in the early 00s and that was still ghastly) affects them more.

But that’s just in the short-term, says Haidt. In the long run, “boys are doing much worse”. There’s a “failure to launch” he says, with boys. However anxious girls are, they are still graduating and holding down a job, he says, whilst many teenage boys turn into young men who sit in their room all day, without jobs, looking at screens. (We didn’t have time for me to go into this in the conversation, but he was suggesting that video games are as much of the problem, when it comes to boys, as smartphones. Which is a different topic and one which has had its own peaks and troughs in terms of cultural panic.)

When I interviewed Haidt, I found him engaging, passionate and very up for a debate. I asked him beforehand if he found this kind of work difficult and he said not in the slightest, because teenagers want change too. To illustrate his point, when he sat down, he asked how many of our audience were Gen Z. After the show of hands, he asked how many of them felt their smartphones made them anxious. The exact show of hands - minus one - stayed. “See?” He said to me. “They’re the first generation to grow up with smartphones and social media and they are desperate to change it.”

Acknowledging that smartphones can cause anxiety and that teenagers might be particularly vulnerable to the anxiety caused by social media seems fairly obvious - and it is not the same thing as wanting a ban. Bans are controversial for good reason: there’s a lot of evidence to suggest that a lot of the time, they don’t work and that it simply drives usage underground. (There’s an interesting convo happening around that, right now, with disposable vapes - and of course a longer-term one is around legalising drugs.)

Will a ban give policy makers a “silver bullet” to claim that they’ve tackled it. (“Teenage anxiety? Oh yeah, we nailed that in the last term! Banned smartphones”) and does it get Big Tech off the hook? We should be lobbying them as much as possible to remove their hookiest features, like the endless scrolling and the dratted notifications, and I wonder if the proposed ban lets them sidle on by.

Before I interviewed Haidt, I had a meeting with 3 academic psychologists (one of whom had contacted me to make sure I knew of the counters to his work) specialising in adolescence: Dr Ola Demkowicz, Dr Lucy Foulkes and Dr Margarita Panayiotou, who explained to me the complex nature of adolescent anxiety and why a ban is a quick solution which papers over the real problems. (Dr Foulkes, who has a brilliant new book out on adolescence, wrote a widely shared piece on this a few weeks ago) Their thoughts, and the other critiques I have read, form the ripostes I offered Haidt in the second half of our conversation.

It is important to note that 2 out of Haidt’s 4 calls to action haven’t really generated critique: no phones in schools (although hardly any schools are enforcing this yet, they don’t have banks or caddies to put phones in, teachers are left to simply plead “no phones!” in lessons, but students still feel them burning a hole in their pocket, check them between classes etc. Obviously most schools can’t give every single student a dumb phone instead of a smartphone, like Eton recently announced they will be doing, but it wouldn’t be the hardest thing in the world to get a wall of lockers for each form and you each have a phone caddy to lock it in for the day) and a more play-based childhood.

Everyone would love their kids to play outside and freely, but going back to it is quite tricky. (This is where Haidt’s libertarian position comes out, which is that we need to let kids safely roam at 6, rather than 10 or 12 - as a London parent, I’m not sure that’s going to happen.)

Criticisms include:

that this is a moral panic, akin to those seen before with any technological advance. It happened over the pocket watch (see Samuel Pepys’ diary in 1665!) the TV, the postal service, the landline (thought to be the cause of 9/10 divorces as housewives just wouldn’t stop gossiping on them, lololol) the microwave. Don’t we just need time to get used to this new technology, to naturally find our feet? Sure, says Haidt, but none of those have caused an increase in teenage suicides.

the other thing that happened between 2010 and 2015 is a massive uptick in public health messaging around anxiety. Talking about mental health, giving it terms, encouraging teens to talk to someone if they felt anxious or depressed. Dr Lucy Foulkes wrote an interesting piece about how our approach might be making teens more anxious. (She’s not suggesting we go back to stiff upper lip, either - it’s more thoughtful than that.) The way I put it when I was interviewing him is: if you tell teenagers again and again that they’re anxious, that their smartphones make them anxious, that they are the most anxious generation, could it make them feel more anxious? Haidt didn’t disagree, but again, he didn’t think that accounted for the uptick in data.

raising the age of consent for social media apps to 16 wouldn’t work because the age of consent now (13) doesn’t work either. It’s very easy to open an app, at any age. Unless Big Tech change this their side, it’s all a moot point. (Can’t actually remember his response on that! So sorry.)

this whole idea of addiction is flimsy, because you cannot measure it the same way as you can substance abuse. Dr Panayiotou draws attention to how the surveys to measure social media addiction are not fit for purpose, by asking you to supplement "social media” in this sentence with “friends”. For eg: “do you think about social media when you are not on it?” (Suggesting addiction.) Now try this: “do you think about your friends when you are not with them?” !!

self-report data is notoriously fallible. How you are feeling one day - particularly for the changeable adolescent brain - is not how you are feeling the next. Also, the way one teen measures their anxiety (very bad) might be quite at odds to how another one does (not that bad). The psychologists I spoke with also argue that while visits to the GP have increased for anxiety, the vast proportion of those teenagers do not return for a second visit, nor receive an ongoing referral. Haidt agreed that self-report data is fragile, but again, not enough he felt to explain the dramatic 2010-2015 uptick in female suicide - which really is a horrifying stat.

data is endlessly open to interpretation. Haidt includes 74 data sets in his book and there has been plenty of criticism about how correlation is not causation to which Haidt responded at length. (I do sort of agree that it would be a remarkably neat correlation.)

that this is a conservative drive to deny teenagers agency. (Lorenz, on You’re Wrong About.) I think that’s bollocks tbh, plenty of lefties are worried about young brains and phones and for good reason! Haidt, unsurprisingly, disagrees with this too.

that a ban would simply drive usage of smartphones and social media underground. When something goes wrong online in future, teens won’t tell their parents, as they aren’t mean to have social media in the first place. Ergo, said Dr Demkowicz, they will be more isolated and anxious than they were before. It would also result in the haves and the havenots, where those with bigger allowances/ more laissez-fair parents, would still have smartphones, while the children with lower resources would not.

logistically speaking, when would the ban start? Do the kids with phones now just age out, and then we start from say reception level kids, or are we taking them away from teens (and let’s be honest, kids) who already have them? This all sounds quite dystopian, not vehemently against it, don’t think any kid under double digits needs a smartphone, but can’t see how this works on a practical level. I actually forgot to ask him about this as there was… a lot on the table.

that academic pressure is consistently cited higher than smartphones by teens as reason for their anxiety. Indeed it came above smartphones in the major survey Haidt uses to illustrate his point about the 2010-2015 uptick. The psychologists I spoke with argued that we need to overhaul our results-based education system. Haidt’s response is that of course teens are feeling academic pressure when they are on their phones all day - they don’t have time to study! (Touché.)

that a ban - and this is the biggest one for all the psychologists I spoke to - offers an easy ‘cure all’ for the complex multi-factorial nature of adolescent anxiety, allowing us to ignore all the other things that might hinder a teenager’s life, namely (and this is my personal point of ire) that youths are being driven out of shared, safe, free public spaces in the UK: since 2010, over 800 public libraries have been shut, and spending on youth services has been cut by 70%. You want to take away their screens, but where do you want them to go? Haidt freely admitted this is the biggest criticism of his work, that absolutely youth services should improve, but that he isn’t saying no screens full stop - go onto a desktop after school, and get into a chatroom, like millennials did! (Ahhh, MSN Messenger.)

that immunocompromised teens, disabled teens, teens from marginalised communities and LGBTQ+ teens, have found such solace and community online. Haidt’s riposte was that the teens self-reporting as most anxious about smartphones are LQBTQ+ teens, because of the prejudice they face online. And that community, again, can be found online via a desktop. Find it hard to argue with that, tbh.

You can probably see that it’s a meaty subject! I hope I’ve conveyed the many vital parts of Haidt’s work - how able he is to defend “his thesis being stressed” as one audience member put it to me after - but that this is a really, really complex field. It’s also important to remember that Haidt is a social psychologist, rather than a psychologist who specialises in mental health, or adolescence. But then, do you have to specialise in adolescence to identify a cultural problem?

I’d love to hear your thoughts! Because as you can see, I agree with him on some bits, and I agree with his critics on his others. And please - do read the book as well as the op-eds. It’s a complex subject and it deserves thorough and careful reading.

I also adored Spent, written and starring Michelle De Swarte, and available on iPlayer now. (It’s much better than the trailer below imho.) It cover tons of issues - the gentrification of Brixton, mental health, the Jewish faith, ageing parents, the many fucked up elements of the fashion industry - whilst remaining as lean as its Peter Pan-like main character, Mia, a fashion model of 20 years who comes home to Brixton after declaring herself bankrupt in New York (whilst still pretending to everyone that she isn’t a) skint and b) homeless). I saw a TV critic criticise it for that very leanness that I love, reminding me - as it should all of us - that taste (and delight!) is so gloriously subjective.

Inspired by comedian and writer De Swarte’s own successful career as a model, it’s both bombastic and endearing (much like Mia herself), with some great one-liners. “You’re like Notting Hill Carnival, Mia. Fun, but you wouldn’t want to go every day.” And when her accountant admonishes her for spending $14,000 on crystals in one year: “you have to spend the poverty out of you”. But it isn’t just smart one-liners - the writing in a scene between Mia and her father, who absented himself from society many years ago is stunningly poetic, and there’s a really gorgeous through-line about how and why we care and if it’s too late for Mia to learn. Almost every secondary (even tertiary) character adds something, which I think is pretty rare. My husband loved it as much as I did.

I’ve recommended Rylan’s new-ish podcast before, but this episode with Daisy May Cooper had me laughing out loud. It’s quite luvvie - there’s a lot of cackling and “love you’s” - but I was in awe of DMC’s candour, on her terrible time at RADA, how she was suicidal at the height of her success and how angry it made her when people suggested (once she had lost weight, because she changed meds) that she was “only funny because [I] was fat.”

There’s also a lovely symbiosis, as Rylan points out a few times, between Cooper’s and his careers: both are from working class backgrounds, both were undermined for a long time since they were taken seriously, both had severe mental health struggles and public divorces, and both believe, semi-seriously, that if they were not in the entertainment industry they would be “doing time”.

It’s also just really really funny and very vulgar. Kudos to the BBC for not editing out the bit where DMC talks about her boyfriend’s “stonk on” and the many ‘cunts’ littered throughout the episode.

This is an extraordinary video. A few weeks ago, Paris Hilton - who in the last few years has become a committed advocate for young people in treatment centres and group homes - testified before Congress, describing the harm caused by the residential treatment facilities she attended between the ages of 16 and 18 (she was force-fed medications, sexually abused and was not allowed to look out of a window for two years) and which she believes is still ongoing. You can’t help but wonder how much of that trauma must have informed her early years in the spotlight. I admire her for fighting to get these military-style boarding schools - which she says preach healing but are riddled with abuse - shut down.

I so enjoyed my tenacious friend and second time bride Katherine trying on over 100 wedding dresses for Vogue in a bid to find one that chimed with her self-described personal style of “unhinged jolie ladie”. (The first nups, incidentally, she wore Jenny Peckham and found, “the fit was better than the flame”.) The thought of trying on one hundy frocks (via 17 bridal appts) makes me feel like an octogenarian labrador, but kudos to KO, because this is a funny, thoughtful and if you’re getting hitched, infinitely useful piece.

“Unless a magician could conjure up a gown that said ‘Amish by day, vixen by night’, finding one that encompassed my, shall we say, oxymoronic personal style seemed unlikely. So, I decided to embark on an odyssey of discovery.”

Nick Hornby, meme curator of the week, also wrote this very good piece about the nature of those ‘best books of the C21st’ lists (which I always find fascinating as I’ve genuinely only ever read about 20% of any given list) and the irritating people who comment furiously when a book they love is not included. I hate naming my favourite books, because I don’t really have 1, or 10, and I will always forget one. He also offered this reminder - which I will not attach to everything I recommend, ad infinitum!

Please remember: 1) My taste is my taste. There are absolutely no objective criteria we can use to decide what is a great book. If I think it’s great, it’s great. If you think something else is great, it is also great. Hurrah for books! And taste!

A pretty good note to end this letter of recs on.

Drop me a Comment if there’s anything that tickled/ intrigued or irritated you today! But just remember…. my taste is my taste. And yours, fellow sailors of the cultural sea, is yours.

Another FABULOUS read on anxiety for this generation is:

The Twenty Something Treatment by Dr Meg Jay.

I listened to it on audible but have bought the book too as it is so useful.

Oh Pandora 😭 my 11 year old is about to finish Y6 and I am ALL OVER THE PLACE with giving / not giving her a smartphone. I don’t want to…but literally her entire 90-person year other than her has one already. Can your v clever techy brother give us all a primer on how he’s managed his brilliant, wonderful, balanced-sounding daughters’ phones! (In the next newsletter please. Have just deleted my own Instagram account in horror 😉) I loved and valued the time and thought you’d ploughed into this interview / newsletter. Thank you ❤️