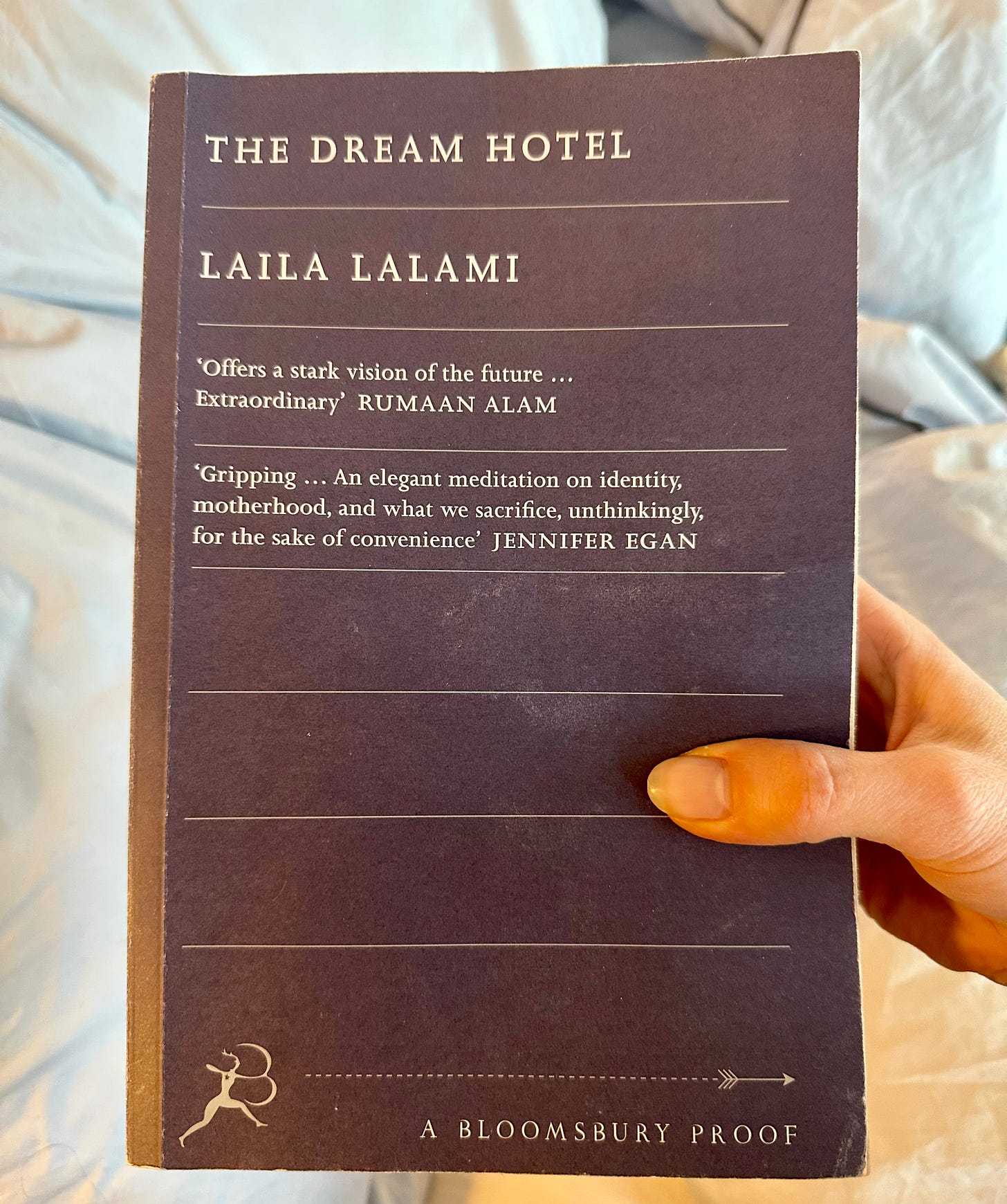

Entirely by chance, I had just finished (and loved) The Other Americans by Laila Lalami—sent to me by ShelterBox book club1—when Lalami’s fifth novel, The Dream Hotel, arrived through my door. It’s a speculative work, about motherhood, marriage, surveillance and tech, reminiscent of Jessamine Chan’s The School for Good Mothers, Helen Phillips’s Hum, Celeste Ng’s Our Missing Hearts and Russell T Davies’s very good and ominous miniseries of 2023, Years and Years. (I have also seen the book compared to Kafka and Philip K. Dick, but I have read neither author, so can’t say if that fits.)

The Dream Hotel tells the story of Sara, a museum archivist who is on her way home to her husband and 10-month-old twins when she is detained at LAX, for having dangerous dreams. It turns out that she has been dreaming about harming her husband. How does the ‘Risk Assessment’ unit know this? Because like most people in this near future, Sara wear a DreamSaver, a device which was implanted in her skull to guarantee good sleep. In the fine print that she rushed past in her insomniatic state (and this terrifies me, because it is absolutely the kind of thing I would do), Sara failed to note that the device tracks and harvests data from its users, as a way of regulating society. Dreams make up a large part of a citizen’s ‘risk score’ and Sara’s dreams have pushed her into the danger zone.

“Once dreams became a commodity, a new market opened—and markets are designed to grow. Sales must be increased, initiatives developed, channels broadened.”

Sara is taken to a retention centre (not a detention centre and definitely not a prison) where she will be retained for 21 days. But 21 days turns out to be an arbitrary number, impossible to quantify, and Sara finds herself in a twisted nightmare that she cannot wake up from. Her twins are growing up without her and her husband is exhausted and confused. Can Sara convince everyone that she is not a threat to her family? Or, as she begins to believe the narrative of her “dark and obdurate nature”, will she fold in half—bend at the waist—and give up on her former life?

The plot is heavy, but there is a playfulness—and deftness—to the way Lalami approaches her themes of immigration, race, gender and motherhood. The proportion of non-white women at the retention centre is much higher than white; at the same time, a white male character claims that his grandmother, who he calls ‘abuela’, is Mexican—because she lived in Mexico for the first 7 years of her life, when her parents worked for the US Embassy—to lend his tortillas a more authentic flavour. (“The story improves the taste. Plus, my grandmother considered herself Mexican”.) This leads on to another theme that Lalami sifts between her hands like kinetic sand: that men are able to play with stories, identities and memories to ‘improve’ the taste—pull it on, slough it off—but if a woman so much as thinks out of line, she will be detained. Sorry, retained.

“To be a woman was to watch yourself not just through your own eyes, but through the eyes of others. [Her husband], on the other hand, was untethered from any judgment except his own, which she found exotic and irresistible all at once.”

The Dream Hotel may be more sci-fi in flavour than The Other Americans, but a lot of the same themes crop up: motherhood, marriage, immigration, story-telling, social contracts and America. It is well-written, meticulously conceived, richly characterised and terrifying as hell. It’s just close enough to be imaginable. Even if this (understandably) scares the pants off you, I think it’s worth reading for Lalami’s deeply human observations; the way in which women must turn themselves upside down and inside out to ‘comply’, is given an apt metaphor in the dream tracker. She’s a master storyteller, Lalami, and I can’t work out why she isn’t better known. The Dream Hotel just made the long-list for The Women’s Prize, so hopefully she will be soon.

I love short stories and I love Curtis Sittenfeld and thankfully, Show Don’t Tell was everything I hoped it would be. In her clever, wry and deeply satisfying new collection, Sittenfeld solidifies herself as someone fascinated by awkwardness and shame. Her stories play with art, ambition, disappointment and hubris—most commonly through the lense of a person in middle-age reflecting on and reckoning with something that happened in their past—and they fling us all over America: Iowa, Alabama, Wisconsin, Arizona.

In the second story, (my favourite), ‘The Marriage Clock’, a movie exec flies to Alabama to try and persuade the conservative Christian author of a best-selling non-fiction book about marriage, to let a gay couple feature in her studio’s fictional movie adaptation of the book. She’s dreading the trip, expecting to find a backwater Jordan Petersen meme; instead, she finds a thoughtful, charismatic and vulnerable man who admits that he is no marriage guru—rather, he wrote the book to try and save his marriage. This unlocks something in Heather, who has been unhappily married for years now. And then the story twists and turns in ways I really could not predict, constantly setting up and undercutting the reader’s expectations with thrilling skill.

Another one of my favourite stories is ‘The Richest Babysitter in the World’, where a woman named Kit reflects on her job two decades earlier as a babysitter to a dorky man called Bryan, who went on to create an Amazon-esque behemouth called Pangea, making him a billionaire. (Bryan once offered her a job, but she refused, and her now husband is furious, harping on about how rich they could now be with her shares.) Bryan and his wife Diane have recently divorced, and Bryan’s texts to another woman have been leaked to the media, causing a public shaming. Kit considers her feelings on the matter. Should Bryan be humiliated because he cheated, or should Bryan be humiliated for his corporation’s terrible labour practises?

“Because the Woley’s split had some ostensibly seamy aspects that contrasted with Bryan’s general orderliness, factions of the public—comedians, social media—delighted in mocking the situation. I understood that people were making fun of him at the available point of entry, but his leaked texts, his apparent wishes to be close to another person and for another person to find him attractive? Those texts, those wishes, were ridiculous and hopeful and vulnerable and human. The reason to criticise Bryan Woley was that he kept a million blue-collar workers under the same crappy conditions that blue-collar workers had always toiled under.”

This notion of a famous person having the same fallibilities as a normie reminded me of Sittenfeld’s last novel (more thoughts on that here), about a pop star who turned out to be a decent dude. It’s something I always expect to find in Sittenfeld’s work: that people are not who we expect them to be and that markers of identity cannot tell us very much about a person’s true nature.

The last story was the most moving to me, because it picks up with Lee, who was the protagonist of Sittenfeld’s second novel, Prep, which I fell so hard for aged 19 that I wrote my dissertation at uni on it. This book shattered me, with it’s themes of loneliness, status-seeking and shame. I was still young enough when I first read it not to realise when I was striving for something that wasn’t good for me, much like Lee does for the entirety of Prep, and I will forever remember the feeling of the scales falling from my eyes, as I read. In this last story, ‘Lost But Not Forgotten’, Lee—kinder, more self-aware, still a little cynical—attends an Ault reunion. I won’t spoil it for other Prep fans, but let’s just say that Cross Silverman is the epitome of ‘peaked too soon’. The denouement I always needed.

Blurbs don’t always reflect a book’s innards, but the one on the back of Holly Brickley’s debut, Deep Cuts—which states that the novel is for fans of One Day, Daisy Jones and The Six, and Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow—knows it’s stuff. This is for those fans! This is a book about a long and enduring platonic love (which intermittently cusps on romantic love), making art with friends, ambition, ego and music.

Joe and Percy meet in college in 2000 and immediately hit it off. Here’s their very cute meet-cute, which opens the book:

“He caught me singing along to some garbage song. It was the year 2000 so you can take your pick of soulless hits—probably a boy band, or a teenage girl in a crop top…

“Terrible song,” I said, forcing a casual tone. “But it’s an earworm.”

We knew each other in that vague way you can know people in college, without ever having been introduced or had a conversation. Joey, they called him, though I decided in that moment the diminutive did not suit him; he was too tall, for one. He put an elbow on the bar and said, “Is an earworm ever terrible, though, if it’s truly an earworm?”

“Yes.”

“But it’s doing what it set out to do,” he said. “It’s effective. It’s catchy.”

“Dick Cheney is effective,” I said. “Nazis were catchy.”

The grin spread again.”

When they first meet, they write songs together, until Percy in a fit of pique tells Joe she doesn’t want a song-writing credit. She moves to San Francisco, writes a music blog and works for a trend-spotting company (this is so early 2010s, made me laugh), but she never loses sight of Joe…and his song credits. (A special thanks becomes a particularly lacerating three words.) They each bring different components to the relationship. Percy is forthright and efficient; Joe is easy-going but edgy. They come together and break apart multiple times, compelled by jealousy, envy, impatience, love, distaste. All the emotions that might accompany a long and storied (occasionally sexy) friendship. The deep cuts of their lives, if you will.

It’s sharp, droll and observant (in a way that feels very now) and vividly recalls 00s and 2010s pop-culture through Percy and Joe’s friendship (with plenty of notes on celebrity, tech, indie sleaze, Obama, 9/11). It’s a good concept and very readable, with a ton of musical references (each chapter is named after a song one or both of them has written, often followed by a newspaper ‘review’ of said single). I don’t really enjoy reading about song-writing (it’s just not my sweet spot) and so I found myself drifting during these parts. If it isn’t already being adapted into a TV series, it won’t be long.

I’d read Brittany Newell’s short story ‘Baby’ in n+1 last year, so I experienced a certain amount of déjà vu opening the Koons-like cover of Newell’s second novel, Soft Core, to find that the story forms the first chapter of the novel. I imagine Newell got a book deal to expand the story and I’m not surprised, it’s a great opener for a book and immediately intriguing.

Set in San Francisco’s strip clubs, dungeons and late-night bars, Soft Core is a surprisingly tender book about belonging and self-identity, told through the trojan horse of a thriller. Ruth is an exotic dancer turned dominatrix known as Baby, who lives with her ex-boyfriend, Dino, an affable, cross-dressing drug dealer with lots of dogs. They are no longer romantically partnered, but Dino is the only person Baby cares about (and vice versa—he is is the only person to call her by her real name.) Then Dino goes missing.

Baby—lonely, grieving, drifting into ennui and self-loathing—enters into a dysfunctional relationship with an older rich man, and a new girl, Emmeline—too fresh, too shiny for Baby to trust—starts at the club. Are these two things connected? Reality starts to warp at the edges for Baby; anonymous notes begin appearing in her locker. Could they reveal what happened to Dino?

The book mainly takes place at night, because Baby sleeps most of the day, which lends it a soupy texture: are we seeing things correctly, or are we just feeling our way blindly through San Francisco’s underground scene, where people perform under alter-egos and keep their soft selves secret? The writing is poetic and spunky (a micropenis has “aquatic cuteness”, a client with a foot fetish cradles Baby’s foot as if it were “a baby bird”) and sometimes deliciously vulgar.

“After my first week of working as a professional dominatrix, my clients began to bleed together. The Latex-lovers and cross-dressers and masochists, the sissies and piss-drinkers and self-described brats—they all got mixed up into one gnarly soup. My sessions didn’t become less interesting, but they did lose their shock value. After a month I could gaze upon the fuzzy butthole of a lawyer bent over my knee and barely register disgust. If I was lucky, I’d enter a flow state; if not, I got bored and pushed on. I got used to grown men wiping well or not at all. Ophelia would call this their Hershey’s kiss.”

What makes Soft Core so compelling is how Newell writes about the BDSM scene with genuine affection and first-hand knowledge, rather than as something cold, or pitiable. It is a job for Baby, no weirder than any other job that involves humans, who are inherently weird by dint of being human. Newell herself is a former dom and the book includes “sensory details” from her own life. I’m not entirely sure the thriller part of the book worked, and it ran out of steam a little towards the end I felt, but Newell is such a stylish, charming writer and her world-building is immersive and vibrant. I am excited to read more of her.

I love it—it’s the only book subscription service I have ever signed up to! You receive a new book every 6 weeks and they have a really global approach to fiction (lots of translated works, not once have I read the book they’ve sent me) and all the money goes to charity. Their choices regularly thrill me: it was also thanks to them that I read and loved 8 Lives of a Century-Old Trickster.

I’ve always bypassed Curtis Sittenfeld books, but maybe I’ve been missing out! Loved these reviews

These sound great. Thx