I’m as interested in why we read, as what we read. A book is nothing—mere object—without its reader. And a reader is nothing without context; our own precise circumstances of being. For instance, I often read because my brain won’t allow me to sleep; it’s the only medium where my racing brain can set the pace. (Like Ochuko, I sometimes fear I read too much.) But what if reading is all you can do? If all other options have—quite literally—been exhausted?

In this guest essay by Make It Make Sense co-author and Books+Bits contributor Bel Hawkins, Bel writes about how Chronic Fatigue Syndrome has shaped her as a reader and how she comes to make ‘those wasted hours’ feel meaningful. I think this will speak to so many people who have, for either short-term or long-term periods of time, been bed-bound. Please do share with anyone who needs to read it.

I’m tired. All the time. Not a poetic tired—this is boring and unsexy, the flat excuse you make for slipping out the side door of a party before it’s even begun. I was diagnosed with mild Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) when I was 25. It’s a notoriously enigmatic condition which depletes your energy reserves. No one really knows exactly how you contract it, nor how to fix it. It means I have to micromanage my energy in order to work, to have a social life, and to avoid crashes that can leave me bedridden for days. I refer to myself as WoW. Worn Out Woman. (There’s so many of us around.)

Sometimes my CFS is undetectable. I’ll be in the supermarket, breezily throwing things into my basket, and it will hit me like a wave. I’ll leave immediately, racing home to withdraw from society until I can handle it again. I’m a social liability. I’m an energetic microclimate. I’m a secondhand phone battery threatening to glare 2% at any minute. Making plans with me is a risk, and making plans feels risky.

It feels dramatic and embarrassing to talk about how tired I am. Everyone is tired. Everyone wants to take a nap. There’s almost nothing worse than reading about a lucky person complaining while the world is on fire. I am lucky: I live alone, with no care obligations, in a slower-paced city, Lisbon. But being tired rules my life. It also rules what I read.

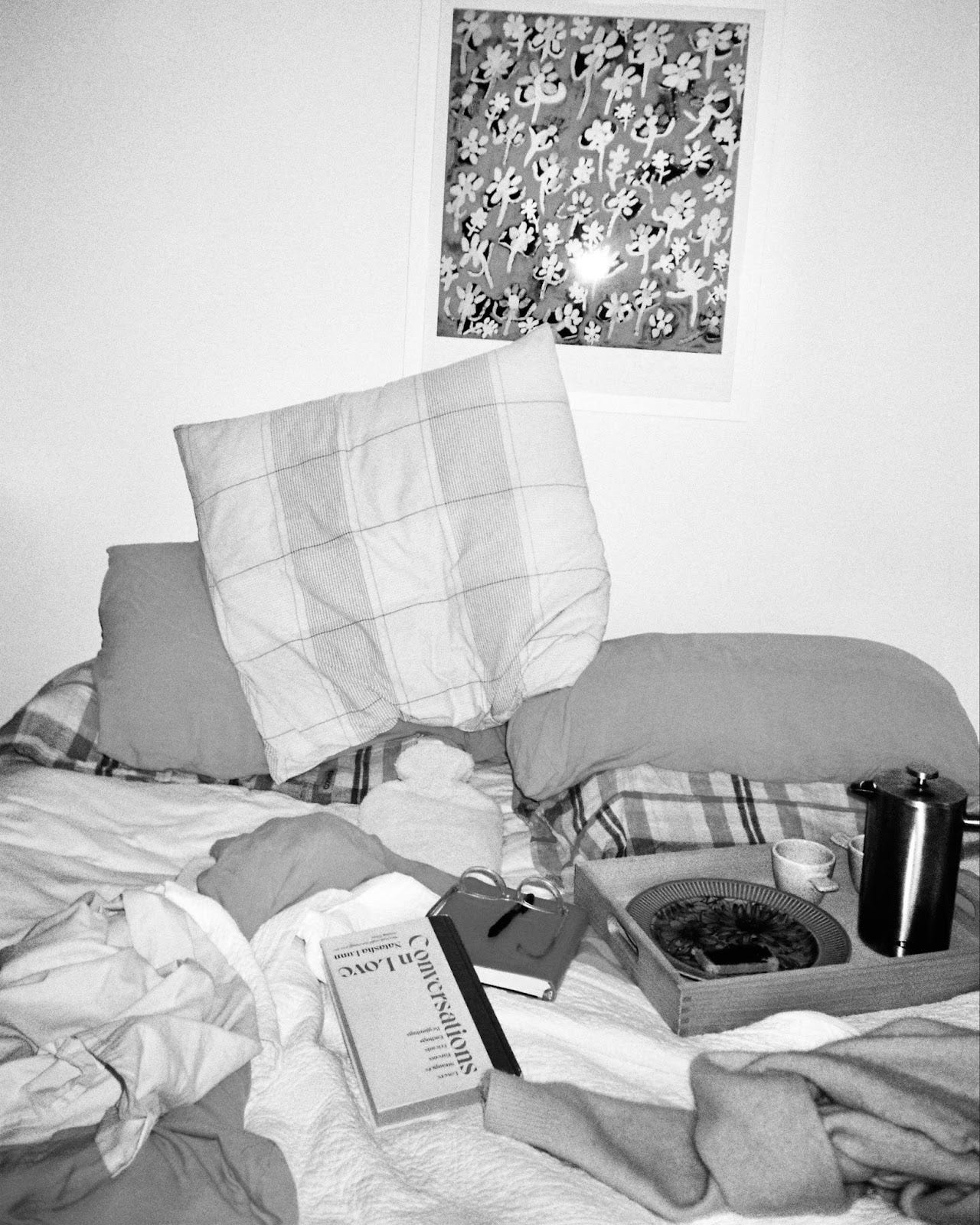

In bed—my soft, safe place—I read. A lot. I read memoirs like Hua Hse’s Stay True, Deborah Levy’s Real Estate, Ariel Levy’s The Rules Do Not Apply. Essays, like Emilie Pine’s Notes to Self and Shon Faye’s Love In Exile. I read until I can see into other people’s lives more clearly than my own. Once I’ve finished reading, I go online and drink greedily: first-person Substacks; screenshots of lengthy text exchanges regaling party dramas; Reddit threads about psychics living in Northern Ireland; my favourite YouTube series about a woman who’s devoted her life to finding the untold stories of Ancient Egyptian women.

I read things that make my time feel useful. I’m not looking for escapism. You can keep your romantasy, your books about dragons and made-up affairs in faraway places. I want to know what’s happening out there, in the real world, where I can’t always participate. I want to know what life is happening right now. Bestselling author Laura Hillenbrand knows this all too well. On a community site for people with CFS, she speaks sharply about the way this disorder affects both her reading and writing life.

“I love to write about individuals who lived lives full of motion, because [chronic fatigue syndrome] leaves me trapped in stillness... Physically, I can’t escape this illness, or even this house, but when I’m writing, I’m not here; I am in another place and time, in another body, living through someone else.”

Over the years, these periods of unexpected convalescence have become a loneliness I’ve grown accustomed to. A private reckoning, where I’m yanked into unwilling rest. My creativity and my fatigue have become codependent. Bed has become where I do my best writing. (I console myself with the fact that many of the greats do this, too: Phoebe Waller-Bridge wrote most of Fleabag under a duvet). It’s like I need to be in that liminal, half-awake place to write.

Until Long Covid—when suddenly, chronic fatigue was under a spotlight, garnering our enigmatic exhaustion a touch of understanding—public conversation about CFS was rare. Because it’s boring, I guess? (It’s boring, no guessing required.) In her wrenching essay, ‘A Sudden Illness’, Laura Hillenbrand (whose CFS is much more severe than mine) writes about working from bed, being able to leave it only briefly, before returning back to the only place that could hold her. It’s this restless reach for productivity while you’re meant to rest that I can relate to most, a determination to make it work when it feels like your body’s doing anything but that.

Would I prefer to be a cool girl out drinking wine at an event with friends? Yes. Is it bleak in here, under the covers, while it feels like everyone else is out? Also yes. But reading stops making it feel like such a waste of my life. It helps make it feel creative. Writer Leslie Jamison talks about this compulsion in her essay collection, The Empathy Exams: “Feeling something was never simply a state of submission but always, also, a process of construction.”

This is how I make peace with my exhaustion. It pulls me away from the real world, into one of imagination: where I read, and where I write. These are the sorts of double-edged swords we use to make sense out of things we can’t control. We don’t get to make the rules; and so we must figure out how we can bend them.

Another thing that happens when you don’t run on the same energy as everyone else is that time takes on its own dimensionality. It melts. It slows. And it definitely doesn’t care about anyone else’s deadlines. I work as a freelance creative, mostly on billable hours, which means that time is literally money. And time spent resting is its lack thereof. This is a very un-fun conversation to have with someone who is paying you by the hour.

Luckily, my overheads are low, and I don’t yearn for elaborate things. I make it work. I figure if I’m learning something useful from what I’m reading while I’m recovering (‘reading smarter, not harder,’) (cringe), some day down the line, one of these niche bits of information will help me impress a baseball-capped creative director on the other end of a Zoom call who might want to employ me, and they’ll be taken aback by how how culturally incisive I am.

When I’m in a less optimistic state, being pulled back to rest feels more like a failure. Or guilty, the way it feels to lie on the internet about your life when off-screen, it’s falling apart. I’m comforted by Patricia Lockwood’s words in her memoir, Priestdaddy, when these feelings come rushing in:

“A trick I often use, when I feel overwhelming shame or regret, or brokenness beyond repair, is to think of a line I especially love, or a poem that arrived like lightning, and remember that it wouldn’t have come to me if anything in my life had happened differently. Not that way. Not in those words.”

This condition makes falling in love strange, too. Letting someone into my bed means letting them into my flailing immune system, which is not the Strong Woman energy I want to exhibit to the world. It means waking up next to someone on weekends can take on this Sylvia Plath-type feeling— not in a poetic way—but more like a state that’s an impossible imbalance of time and energy.

“Saturday morning and I am at the old game of catching time between my fingers as it is running, forever running away.”

It often feels like I’m being left behind. Like the party’s been and gone, the train’s left the station, and I’m still at the back, pulling on my boots. You don’t make memories like this. You don’t serendipitously bump into a hot stranger and get talking. But you do get solitude. And this strange gift of idle time. Books, books, books. I am always able to come back to books. They are permanent, when nothing else is.

I can't really articulate how MUCH I relate to this Bel (fellow sick, mid twentines, sometimes bedbound ferocious reader) I feel (complimentary) that this essay has been pulled straight out of my brain because I have something very similar on my laptop about why I read as someone who is sick. There are too many lines to pull - but the one that resonates the most is: 'I read things that make my time feel useful. I’m not looking for escapism. You can keep your romantasy, your books about dragons and made-up affairs in faraway places. I want to know what’s happening out there, in the real world, where I can’t always participate.' - I so often get the question of 'how can you read about 'horrible' or 'real world' events when your life is so stressful (always a veiled insult when someone says this lol) and they assume I would blindly only want to read fantasy to 'escape' my life - but as you say, I want to be IN the world I can't be in, I want to be involved because I'd much rather be out there than in my fucking bed but I can't change that reality so the least I can do is manipulate how I spend that reality.

Also this line; 'Would I prefer to be a cool girl out drinking wine at an event with friends? Yes. Is it bleak in here, under the covers, while it feels like everyone else is out? Also yes. But reading stops making it feel like such a waste of my life' deeply relatable. It is bleak here under the covers but at least I am reading some good books - as you perfectly word it 'They are permanent, when nothing else is.'

Will be sending this to anyone who asks why I read so much from now on. Thanks Bel 💖