Before I started this project, I knew little about Colleen Hoover beyond her name as putdown. I used it myself, when I wrote a post recommending books for teenagers. “Not a Colleen Hoover in sight” I wrote, as if it was a positive statement rather that a neutral fact. I’m ashamed of that throwaway comment, because I cannot bear cultural snootiness. I have always believed that it is much harder to make art with mass appeal, than it is to make something niche. It is hard to create an intimate world, in which many, many people feel like they belong.

My personal taste runs more to literary fiction than it does commercial fiction, but I have never been someone who clutches their pearls over not terribly literary books for women selling in huge volumes. After all, it’s hardly new: Jackie Collins, Danielle Steel, Sarah J. Maas, Stephenie Meyers, Barbara Cartland, E. L. James, to name just a few. (That’s leaving aside the fact that it’s only ever books by women, for women, that garner this kind of controversy.) The reason I never read any Colleen Hoover was simply because I just didn’t think it would hit either of my reading requirements: that a book must nourish my mind, or quieten my brain monkeys.

But then I realised I was missing a trick: a chance to learn about something that is making incredible amounts of women feel seen. I wanted to figure out for myself what has made Hoover so phenomenally successful - and controversial. (You can barely move for think pieces on how Colleen Hoover is the armpit of literature.)

Some cliff notes for the unfamiliar: The 44-year-old Texan mother of three has written 26 books and sold over 32 million copies. In 2022, more people bought her books than the bible1 and she held 6 out of 10 spots on The New York Times paperback fiction bestseller list. She is still a long way from being the bestselling author in her category (Fifty Shades’ E L James has sold over 165 million books, Twilight’s Stephenie Meyers has sold over 250 million) but she is certainly the most talked about right now.

Hoover self-published her first few books on Wattpad, before moving over to a trad publishing house, Atria, in 2016. Her success is specifically tied to TikTok’s book arm, BookTok (the unparalelled influence of which is now widely accepted) and specifically tied to tears. (There are currently 51.8 million crying TikTok videos relating to Hoover’s most famous work, It Ends With Us.) The Colleen Hoover hashtag has had over 2.4 billion views.

The question was no longer whether I should read some Colleen Hoover and more, why had it taken me so long?

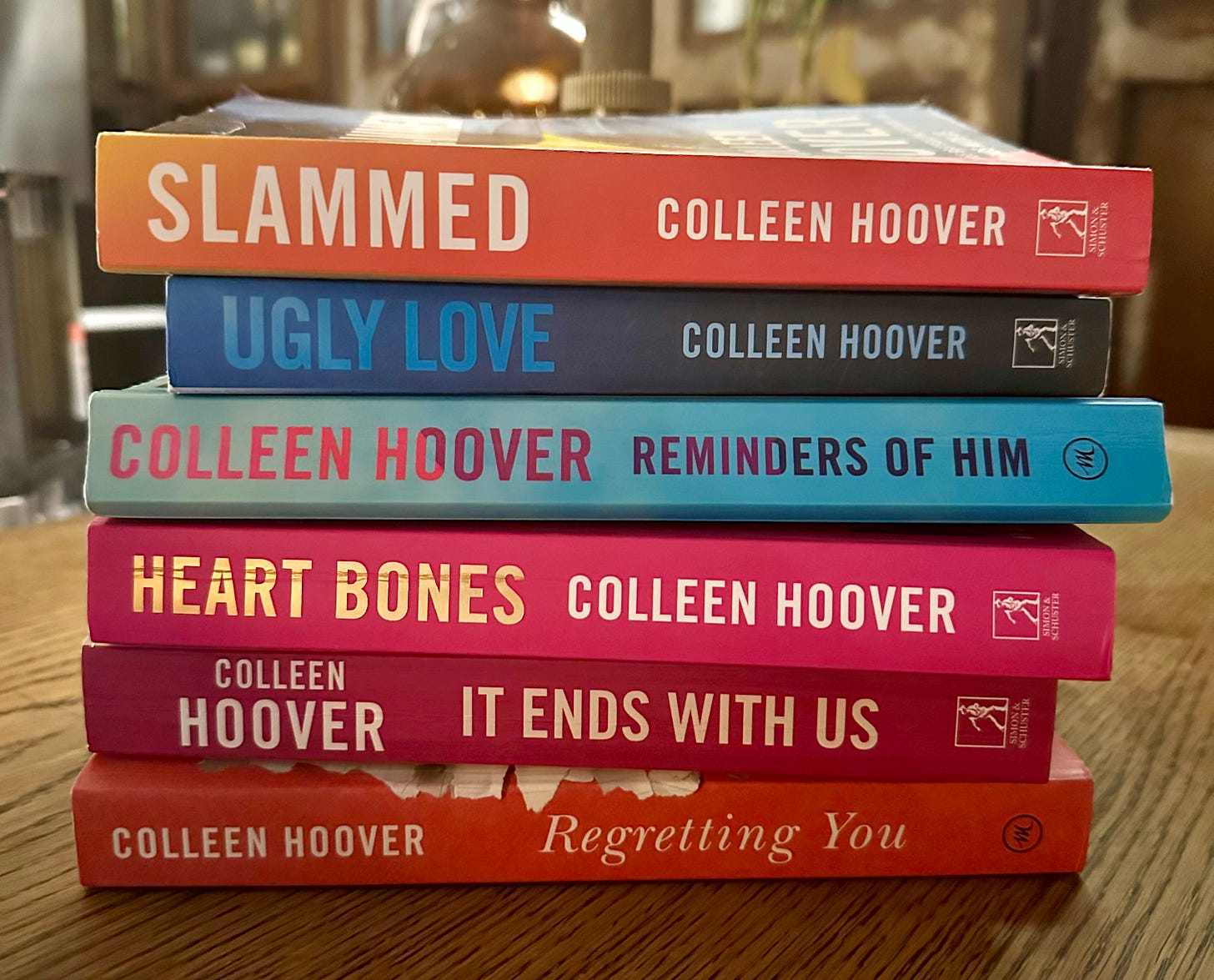

And so I embarked on a month-long gorge of CoHo’s canon: 7 of her 23 books, that I bought off Vinted in bulk. I enjoyed reading them. I found it hard to stop reading them. I read each one in a night, even when it meant I was exhausted the next day, as the thought of putting them down made me feel irritable. And when the end came (there had to be an end), I was sad. Almost as sad as I had been while reading them. In short: they are utterly addictive.

There is also a clear formula. Some parts of the formula jar, while other parts intrigue. I’ve broken it down into 9 tropes, below, and considered what it is that makes the books so readable, and the specific things that hooked me. I end on some thoughts - naturally - on the It Ends With Us controversy.

THERE WILL BE SPOILERS!

People are very young

The books are written through a working-class perspective, where characters don’t have the luxury to fuck around finding themselves, before leading responsible, adult lives. To quote Beyah in Heart Bones on gap years:

“When you’re poor and you take a year off high school, you’re throwing away your future… But if you’re rich and you take a year off, it’s considered sophisticated.”

Sometimes characters are unrealistically young for the lives they are leading, which is thanks to the author’s romantic mind, a lack of research, or perhaps both. In It Ends With Us, Ryle is a 30-year-old neurosurgeon (the typical age to begin practising neurosurgery is 34), while Lily Blossom Bloom2 sets up her own flower shop at the age of 23.3 In half the books I read, there is a character who has a child at 18 (we’ll come back to this later.)

The other reason Hoover’s books are about very young people is because they are considered YA, which is 12-18 years old. But YA (which stands for ‘young adult’) is a strange category - more than half of the people buying YA books are over 18 years old and the majority are between 30 and 44. Hoover’s characters might be very young, but her readers often aren’t. Which suggests that those child-like top notes of melodrama (which we will get to) are offering some sort of fairytale, where terrible things happen, but everything turns out okay (ish) in the end.

People work extremely hard

This is my favourite thing about Colleen Hoover’s books. They might feature Gen Z aged characters, but contrary to all the memes about (poor old) Gen Z, these characters grind to make bank. (Maybe because the author is not Gen Z.) No-one makes a quick buck, no-one works in marketing or digital media, everyone has wholly respectable jobs: pilot, teacher, nurse, neurosurgeon, small business owner and they work long hours. (It Ends With Us is the exception: where Marshall and Allysa are very rich.)

There is a reason why a lot of young women in contemporary fiction right now are sad, angry, confused (aka, ‘sad girl lit’.) But I didn’t realise how fatigued I had become of books about messy middle-class women until I read my collection of Hoovers. The experience of reading her books is emotionally wrought, but it can also be humbling. To quote Kim Kardashian - who absolutely does not exist in the CoHo universe - they get their fucking ass up and work. This is the economic reality for most of her characters. To work a lot is necessary in order to live.

Hoover reminds me of Elizabeth Strout. Both authors are interested in working-class concerns, small American communities, tragedy, trauma and story-telling. Their characters are deeply invested in their community, in showing up, in integrity. Strout is a more sophisticated and subtle storyteller than Hoover, but Hoover’s characters also tell themselves stories in order to live. They may not quote Joan Didion, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t grappling for a meaningful life. A lot of the time, they deny themselves the lives they wish to lead because they are not sure they deserve a big life, or a big love. Sometimes that can be devastating, sometimes it can be frustrating, but it’s also a palate cleanser.

People are corny and horny

They are cheesy - in Ugly Love, Tate observes: “Brain = liquid. Heart = Butter” - and they are corny, in that they say basic things about terrible events. Here’s Will, in Slammed, performing at a poetry night:

Death. The only thing inevitable in life.

People don’t like to talk about death because

it makes them sad.

They don’t want to imagine how life will go on

without them.

(Italics and bold type do a lot of heavy lifting in Hoover’s work.)

And they are porny. To quote Regretting You: “He feels like a professor of my body, and I feel like an inexperienced student.”

There’s a lot of sex in Hoover’s books - a lot of “inside of me”/ “inside of her” which can feel like more of an archaelogical dig/ autopsy, than a sex scene. But as someone who generally finds sex scenes excruciating (I just think they’re impossible to do well), I didn’t find them any more toe-curling than usual. People also have earth-shattering sex, all of the time. Every single man is a lover of extraordinary skill. This is the romance of the genre in full thrust4 and the escapist, idealistic appeal is easy to understand. Honestly, you just have to roll with it.

People have been through shed loads of trauma

In Slammed, 18-year-old Layken loses her father, followed shortly by her mother. She falls in love with her neighbour, Will, who was also orphaned as a teenager and is also now the sole caregiver to his younger sibling. In Ugly Love, 18-year-old Miles loses his baby in a tragic accident and then his girlfriend leaves him. In Heart Bones, 18-year-old Beyah finds her mother overdosed in a trailer, before travelling across the country to live with the father who abandoned her. In Regretting You, Morgan’s husband dies, whereupon she finds out he had been having an affair with her sister. In Reminders of You, 21-year-old Kenna goes to prison for 5 years after a tragic accident results in the death of her then boyfriend. While incarcerated, she gives birth to a baby girl, who she is not allowed to touch before she is taken away. In — oh you get the gist.

The high quotient of trauma is interesting, because of the time in which Colleen Hoover is writing. If she wrote these books in the 90s, she’d be fitting right into the misery lit canon. But much has been written, particularly in the last few years, on the limitations of ‘trauma porn’ in literature. In Colleen Hoover’s books, trauma is back story, plot and character. Someone being orphaned at 15 is a descriptor used in the same sentence as him liking lollipops (which are unnervingly referred to as ‘suckers’.)

Laying it all out like this makes me wonder what the heck I was thinking reading them all and back-to-back at that. But there’s something about these people going through horrendous things at such young ages and finding this unbelievable (and it is, for the most part, unbelievable) resilience and humility and hope - so much hope - that is addictive. Anyone who does not find a fresh Colleen Hoover a seductive prospect simply hasn’t read enough of them.

The Hoover effect is cumulative. The more of them you read, the more you crave the formula of: tragedy + hardscrabble life + sex + hope + new beginnings. It’s not unlike a telenovela, or a great soap.

That said, I became increasingly uncomfortable with the unconscious idea threaded throughout her books, that people must go through immense amounts of trauma and grief, to deserve love. There is also an idea at play that the antidote to shed loads of trauma, is earth-shattering sex. It hooks the reader in, but it feels grubby.

People (men) are possessive

A lot has been written on the misogyny in Hoover’s books and I will say, the men are intense. In Ugly Love, the male characters are uniformly possessive. Miles observes of Rachel, his 17-year-old classmate who he has just met:

“You’re gonna fall in love with me, Rachel”

“She’s mine”

I send the picture in a message to Ian that says “She’s gonna have all my babies.”

He might be the first 17-year-old boy to ever text this.

Later, Tate observes of Miles, “his mouth is so possessive”. When Corbin finds his sister Tate and Miles tangled around one another5, he inexplicably shouts:

“You’re not a brother, Tate. Don’t you dare tell me I’m not allowed to be pissed.”

Between Corbin and Miles, Tate is in one hell of a wonky conservatorship.

Interestingly, Ugly Love is the only book where I came across a fuckboi. But even then, Dillon is a parody of a fuckboi rather than a fuckboi in any believable sense of the word. This is another thing that makes Hoover’s books appealingly out of whack with popular culture: no fuckbois, no ghosting, but plenty of bossy, brooding men. With all the Byronic brooding and melodrama, it’s kind of giving Wuthering Heights. Hoover would have fit right into the C19th’s Gothic era.

People do not contain multitudes

They are good, or they are terrible, and they aren’t anything in between. Ugly Love’s Dillon is completely reprehensible. Even his own friends hate him. Reminders of Him’s Ledger, meanwhile, co-raises his dead best friend’s child, helps a former colleague recover from addiction and coaches T ball to little kids while managing his own business. The man is 100% munificence biltong.

Colleen Hoover renders people 1D in a distinctly appealing way. This speaks to me, and I suspect many others, because I find emotional greyscale difficult to interpret. If I lived in Colleen Hoover’s land, I would be very happy. (Although I’d probably be orphaned, so maybe not.)

People have hardly any friends. Those they do have, show up

I don’t think Colleen Hoover is making a social point about how we’re all attempting to be in touch with too many people, here. Rather, the extremely small friendship circles are a byproduct of people spending so much of their time working and characters frequently being socially reticent. They are introverted, or socially awkward, or just not interested. Not to read too much of the author into her own work (a terrible and irresistible habit) but Hoover is shy and finds the hullaballoo around her work excruciating. Her mantra is: head down, hold your family close, work hard. Not unlike many of her characters.

People have wild names

I’m writing this as someone called Pandora, granted, but the characters in these book sound like they were named by Chat GPT after it’s office Christmas party: Beyah, Layken, Caulder, Ryle, Corbin, Diem (named after ‘carpe diem’). I wonder if this is partly an US vs. UK lost in translation thing: there are plenty of names which are common in the States that sound made up to the British ear: Peyton, Caden, Parker, Colt. Sarah Palin’s kids - and I think about this weirdly often - are called Trig and Track.

Wacky baby names can function as socio-economic signifiers, they can be a form of political agitation, they can be part of a generational trend or you could just be Elon Musk. What is interesting, here, is that unique names are typically the preserve of higher income brackets (where, as psychologist Michael Varnum puts it, there is “more opportunity to innovate”.) I like that Hoover bucks the trend. It is proof of her romantasy: a genre which is technically about dragons and crowns and thorns, but I think is also about triumphing against the immense odds, of falling in love with hunky neighbours, of naming your baby after Carpe Diem.

People are pro-life

I have no interest in guessing at Hoover’s political leanings, but her characters are uniformly pro-life. In that, abortion is not mentioned in any of the 7 books I read, and there is a lot of teenage pregnancy.

In Regretting You, Morgan becomes pregnant aged 17 with a man she does not love, so she marries him and has her daughter, Clara. In Ugly Love, Miles gets his teenage girlfriend Rachel pregnant, which is awkward because she is about to become his step-sister. In Reminders of Him, Kenna finds out she is pregnant aged 21, at the start of a five year jail sentence, but again - there’s never any suggestion she would terminate the pregnancy.

Hoover’s writing lense is working class, white (exclusively, I think), middle America. Pro-life would not be surprising.

And some thoughts on the controversy around It Ends With Us

I understand why Blake Lively’s press tour bombed and while though the film was pretty loyal to the source material (and not, actually, a terrible movie)6 I understand why a lot of people were conflicted over an entertaining movie about domestic abuse being made in the first place. And the accompanying colouring book was a marketing fail up there with Jeannine Cummins’s barbed wire manicure.

But the comments I read afterwards - why didn’t she leave? And why are the abuse scenes so blurry? - made me want to howl. How do we still understand so little about domestic abuse, when it is devastatingly prevalent?7 You only need to do a light google of abuse and trauma to know how common it is for the memory and mind to shut down and/or erase things for self-preservation - leaving that person vulnerable to gas-lighting, their memories malleable to re-writing - and to know how hard it is to leave, because they are scared, because they have nowhere to go, because they can’t get their head around someone they love wanting to hurt them. These stories exist in real life, and they are everywhere.

It Ends With Us is based on Hoover’s own life. In the book’s epilogue, she writes:

“My father would repeatedly show remorse and promise to never do it again. It finally got to a point where she knew his promises were empty, but she was a mother of two daughters by then and had no money to leave… I fashioned Ryle after my father in many ways. They are handsome, compassionate, funny, and smart - but with moments of unforgiveable behaviour.”

It is not the best book I’ve read on domestic abuse. (I’d recommend Meena Kandasamy’s shocking and lyrical work of auto-fiction, When I Hit You.) But I wholly disagree with the idea that the book, as Vogue India suggests, “sells intimate partner violence as YA romance”. The book is very clear that it is a book about the insidious, surreal and toxic cocktail of abuse, remorse and gas-lighting. The romance of the book is not the violent relationship. (The allusion of romance is quickly shown to be love-bombing and coercive control.) The romance is the relationship from Lily’s past that sustains her, and ultimately helps her to leave her violent husband. I can’t work out whether these kind of observations are bad faith readings - which are motivated more by the quality of Hoover’s writing - or if people simply haven’t read the book.

Like every type of art and culture, the success of Colleen Hoover does not exist in a vacuum. Her success is a reflection of how social media - and digital consumption habits - have come to shape our tastes. I read somewhere that this kind of white mediocrity is rewarded by BookTok and I don’t know enough about BookTok to say if this is true, but it wouldn’t be out of whack with the history of the arts, if it was.

I don’t think Colleen Hoover deserves the kind of insane readership she commands. Even Colleen Hoover does not think she deserves this kind of monopoly: “My feed became all Colleen Hoover stuff,” she told The New York Times in 2022. “I just wanted to see cat videos, you know?” But neither do I think her books are the downfall of civilisation - or an armpit, or a butt hole, or a cesspit - or, as I keep on reading, ‘not books’. Let me make this clear:

By dint of publishing books, Colleen Hoover is a writer; and by dint of reading those books, people are readers.

I was immersed in CoHo’s world for a while. I no longer am, and I don’t think I will be again, but I understand why other people might want to stay there. I understand why so many people feel drawn to the melodrama and the romantasy, and also - and this is key - the simplicity: people with simple desires, living simple lives, with one or two friends. Little time is spent on phones, politics are never mentioned, TV is only ever alluded to and things are black and white, good or bad. That is the most enduring - and endearing - fantasy of all.

one of my best friends pointed out, with genuine curiosity: who is still buying the bible? They can’t all be christening presents

no-one in the book is aware of nominative determinism

Hoover notes that for the book’s (controversial) film adaptation, the characters were aged up, because her age range is out of kilter with the contemporary tropes of mainstream popular culture

intentional

to quote Casey Aonso, “he’s a creep, she’s on heat”

I went to see it, alone, in the name of research

a quarter of British women - 1 in 4 - will experience domestic abuse in their lifetime

I loved reading this, even though I have no interest in Colleen Hoover! Think I enjoy hearing you discuss something you have mixed feelings about…

You were made for Substack and these geeky longreads. <3