This 1929 'divorce novel' will make you laugh and cry

Ursula Parrott's Ex Wife is enjoying a deserved renaissance

“Freedom from men? Which of us is free who is emotionally absorbed in any man?”

I cannot believe Ex-Wife was written almost 100 years ago. I keep thinking this while reading the principal ‘divorce novel’, which scandalised America when it was published anonymously in 1929. (Author Ursula Parrott was soon outed by a gossip column.) Some of it, like the casual attitude towards battery, is thankfully out of date. But so much of what the Ex-Wife’s protagonist, Patricia, a 24-year-old divorcee living in New York, thinks and feels and experiences, feels shockingly modern. I am not sure whether to be relieved or depressed by that.

The book begins in 1924, when Patricia has separated from Peter, to whom she was married for two years. From the brilliantly deadpan opening paragraph, I was hooked.

“My husband left me four years ago. Why - I don’t precisely understand, and never did. Neither, I suspect, does he.”

Peter and Patricia lived a glamorous, modern post-war life: well-dressed, well-watered and socialising nightly. Patricia works as a fashion copywriter for a department store. Things begin to go wrong when she gives birth to a son, after Peter has made her promise (as if she can control the outcome) “no baby for years and years.” Peter worries how to support a child, that the baby will hurt Patricia, but mostly, “whether I will ever be pretty again”. Patricia goes home to her parents in Boston to have the baby. “I was crazy about him” she says touchingly of baby Patrick. Peter comes to visit and “was so delighted that I was thin again, that he did not talk about the baby at all”.

A few months later, Patrick dies - we are never told how, it’s glossed over very efficiently - and Patricia returns to New York. She is devastated but Peter bans grieving and so she tries to carry on with her life as before. They never speak of Patrick again. I found this extremely painful to read, as I’m sure many readers will. A few months after this, Patricia cheats on Peter with his friend. She tells Peter, thinking that it is all within the flexible confines of their marriage, given that he has cheated on her constantly and showily since they met, with a selection of whom Patricia calls, “the not so happy wives”. But Peter shocks Patricia, insisting, with a newfound puritanism (aha!) and increasing levels of domestic violence, on a divorce. Patricia has sullied herself (I suspect as much by birth, as much as by man) and he can never see her as pure ever again. Poor Peter. How she has wounded him!

“He would sit on the edge of my bed, and say, ‘Patty, the complete slut. So pretty, too bad you are a slut. But you are a lovely one.”

(Yes, Peter is a terrible human being. But given the reaction to him in both the book, and in critical reviews of the time, he is a more acceptable being than an unattached female one.)

During a six month semi-separation (they still live together but Peter spends weekends with his new girlfriend, Hilda), Patricia becomes pregnant again. When she tells Peter, he throws her through a glass door. No-one says anything about this. Patricia finds a doctor who will perform an abortion. He is at first kindly (“you will survive this, you know”) and then creepy (“I do wish, if you and your husband separate, that you would let me know from time to time, how you are getting along.”)

(This is all in the first chapter, and the introduction, incidentally - I have not give any major plot points away.) The novel then follows a heartbroken Patricia as she tries to find her footing as a single woman in New York. At times, I genuinely feel like it could be a book about a single woman in 2024:

“Had a facial didn’t you, Pat? Looks grand. I did some wangling for you this afternoon; telephoned Ned to bring Charlie along with you.”

Had a facial didn’t you, Pat!

Now, it’s all sounding pretty bleak, I know, but it’s also so compelling, wryly funny and stuffed with captivating morsels about life in 1920s New York. As a divorced woman, Patricia is now “in class two” says new best friend, Lucia, who is older than her, settled in her divorced singledom, kind and curious, wildly glamorous and determined to help Patricia embrace her new freedom.

“Lucia, I’d like to be harder, inside. To try to take all this sort of thing as men are supposed to take it, for the adventure, for the moment’s gaiety - perhaps for the warmth and friendliness and anaesthesia against - against feeling so alone.”

To which Lucia replies:

“Finish your cigarette and run along. And if you can really adopt the alleged masculine attitude towards sex, you’ve got all of New York to console you… New York on a short-term lease, while you have the looks and the clothes for it. I’m betting you can’t thought. Not many women can.”

Their friendship is the real love affair of the book. Patricia notes that she never had female friends before she met Lucia and she probably never would have, other than the wives of her husband’s friends, if Peter hadn’t left her. Indeed, Lucia is her only friend - not many women trust her, as a young, attractive, divorced woman, and she does not trust many other women. It’s a reminder that, in the same way Friends was quietly radical for showing friends living together (rather than young people going directly from living in the parental home to living with their spouse), that Ex-Wife is revelatory for it’s depiction of female friendship.

Patricia and Lucia’s conversations are also fascinatingly revelatory about this post-war period of rapid cultural change: towards women and work, sex (this is the decade latex condoms became available), culture and fashion.

“Of course, Lucia, there are the scruples that are left over from the way one was brought up.”

“Yes. But I think chastity, really, went out when birth control came in. If there is no ‘consequence’ - it just isn’t important. People’s ideas - the things they say about affaires - begin to shift enormously, and their ideas are half a generation behind their conduct - their experiments.”

“The thought of going out and getting me fifty lovers doesn’t stir me much, though Lucia. What’ll I have in the end? My memories, I suppose. Hell! Memory may have been some comfort to the Victorians, judging from their poetry, but I don’t seem to be able to work the miracle on it.”

Pat and Lucia wear the most brilliant outfits, frequently copying Parisian couture - I loved googling the references, such as Vionnet. Ex-Wife is set squarely in the middle of prohibition (1920-1933) which a few states, including New York, mostly refused - there were over 30,000 speakeasies in New York during the 20s - and the upper middle class drink with wild abandon. Indeed, Peter blames the breakdown of their marriage on his encouraging Pat to drink as much as him.

Reading Ex-Wife feels like being sucker punched. But it also feels so deliciously prescient at times, like Pat’s quarter-life ennui. “Did you accomplish everything else you set out to do in life just like that, Pat?” Lucia chastises Patricia, when she remarks that she isn’t where she wants to be, aged 25. (How we’ve all been there.) Patricia’s reply makes me laugh out loud:

“Hell, no, but I’m a Futilitarian, so it doesn’t matter. I am futile, you are futile, they are more futile.”

Patricia’s tales on the dating market are also very funny, with lots of peculiar detail. She dates some weirdos, some bounders, and some very lovely men, like Kenneth and Noel. Patricia is curious, thoughtful and resilient - there was not much sympathy for anyone in those days: the war had only recently ended, and you were alive, what could you possibly complain about? - and she tries so hard not to dwell. The moments she allows herself to sink, though, are filled with a pathos that will resonate with so many young women today: what is my worth? What do I stand for? Will anyone ever love me again? And there’s a scene with Nanny, which I won’t spoil, but Patricia lets her guard down and my god, I sobbing reading it.

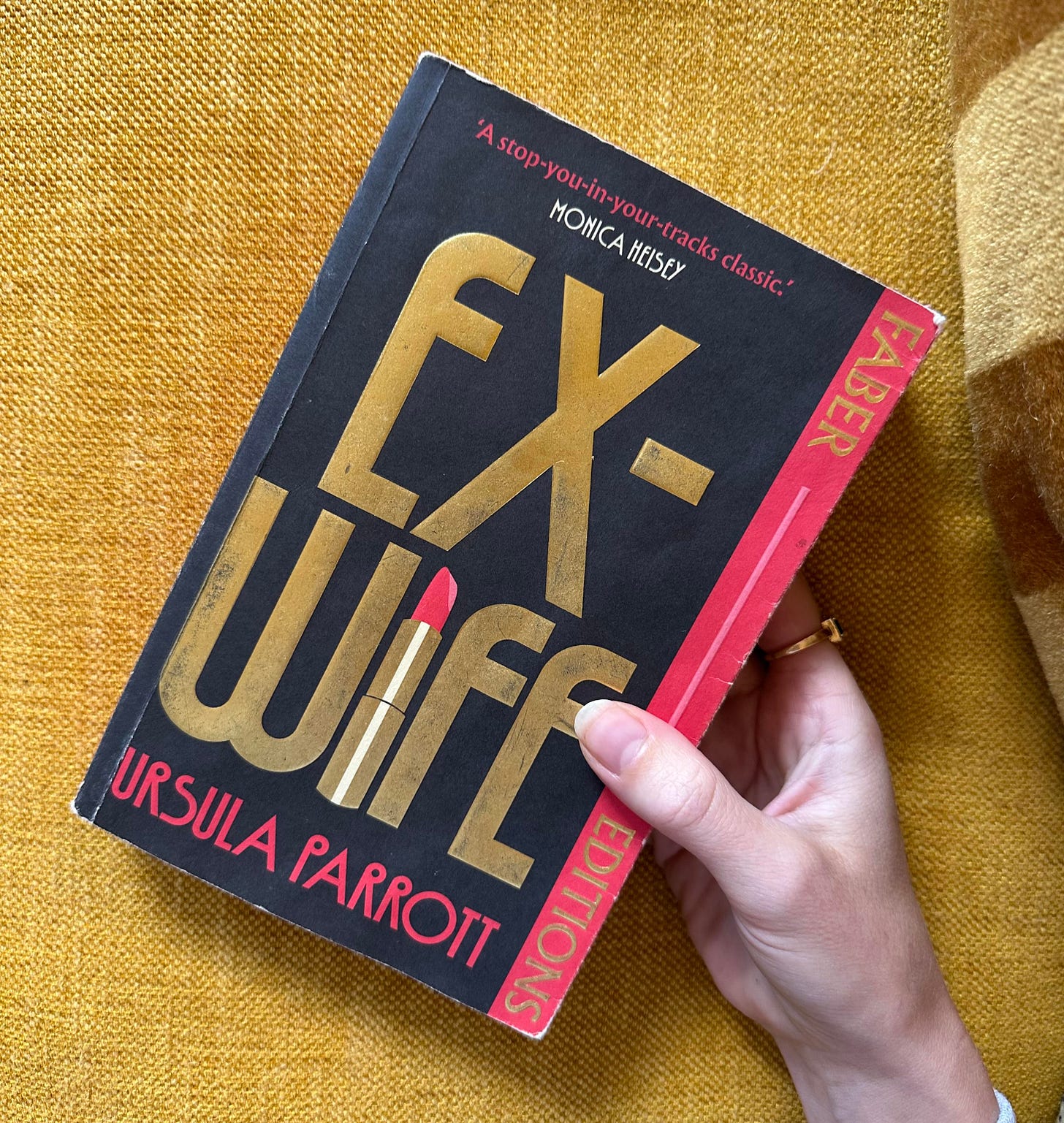

The reason why I came to read this book - I am astonished that I had never heard of it before - is because it was recently reissued by Faber Editions, with a new introduction by screenwriter and novelist Monica Heisey. The book was very famous at the time of publication and made Ursula Parrott very famous and rich indeed, but had fallen into anonymity by the 50s. It felt like some weird sort of kismet, writing about the book today, as this evening I am interviewing Katy Hessel about her book on forgotten female artists, many of whom were also very famous in their day, only to be later forgotten.

In her introduction, Heisey reveals that Ex-Wife was inspired by Parrott’s own life. Born Katherine Ursula Towle, she married Lindesay Parrott, a (later very famous) reporter for The New York Times, when she was 23 and he was 21. Like Peter, Lindesay issued a diktat: there were to be no children for a very long time. He wanted to enjoy the freedom of a post-war New York. When Ursula became pregnant soon after they married (because it is 1923! Birth control is not formally recognised until the 30s and nor is it - nor is it even now - 100% effective) she hides the pregnancy and goes home to her parents in Boston, where she has the baby in secret. Leaving baby Marc to be raised by her parents and sister, she returns to New York. When Lindesay finds out about Marc, two years later, he divorces Ursula, refuses to give her any money and then - ! - blacklists her, so no editor will commission her as a writer. Isn’t that lovely? She isn’t even mentioned in his obit.

Parrott wrote Ex-Wife in desperation - a young, broke single mother - and published it (initially anonymously) to immediate success. It sold 100,000 copies and was made into a film called The Divorce. Norma Shearer won an Oscar for her performance as Patricia.

The rest of Parrott’s life is really very sad. She did not acknowledge Marc publicly until he was 7 years old and their relationship was a difficult one. In his afterword - again, fascinating - Marc writes that Ex-Wife was “a piece of furniture and an albatross” in his life: always there, but a “bad luck bird”.

“My mother worked like a galley slave: I well recall the chaos and tension of making those eternal deadlines for Cosmopolitan, or Women’s Home Companion, long gone now. She and a handful of her peers made more money, I think, than any American women could in that time, except those screen actresses in fairly steady employ… [But] she went through every penny of it, and more.”

She spent it on “houses, cars, servants, travel and the better products of Bergdorf Goodman and Bonwit’s" and, of course, divorces - she was married four times.

Parrott was regular gossip fodder in the press for her failed love affairs, her alcoholism, her various scandals (she tried to break a man out of military prison; she stole $1,000 of silverware from a friend’s house). She died aged 58, alone, on a charity ward, of cancer. I find that almost unbearable.

“My mother lived for a while like the king in the Yeats poem who packed his wedding day with parades and concerts and volleys of cannon: “that the night might come.” It came for my mother, in ruinous style; but she may have felt that the day was well worthwhile.”

Whether or not it was worth it, Ex-Wife is testament to her life, to divorced women, and to her brilliance.

Photo credit: International Newsreel Photo, via Darin Barnes Collection

Is currently 99p on Amazon for kindle. Just bought it.

to those who received this as a mail-out (not on the app, which btw is a much better reading experience!!) I am so sorry for the typos, which have now been fixed