Or perhaps a milliner.

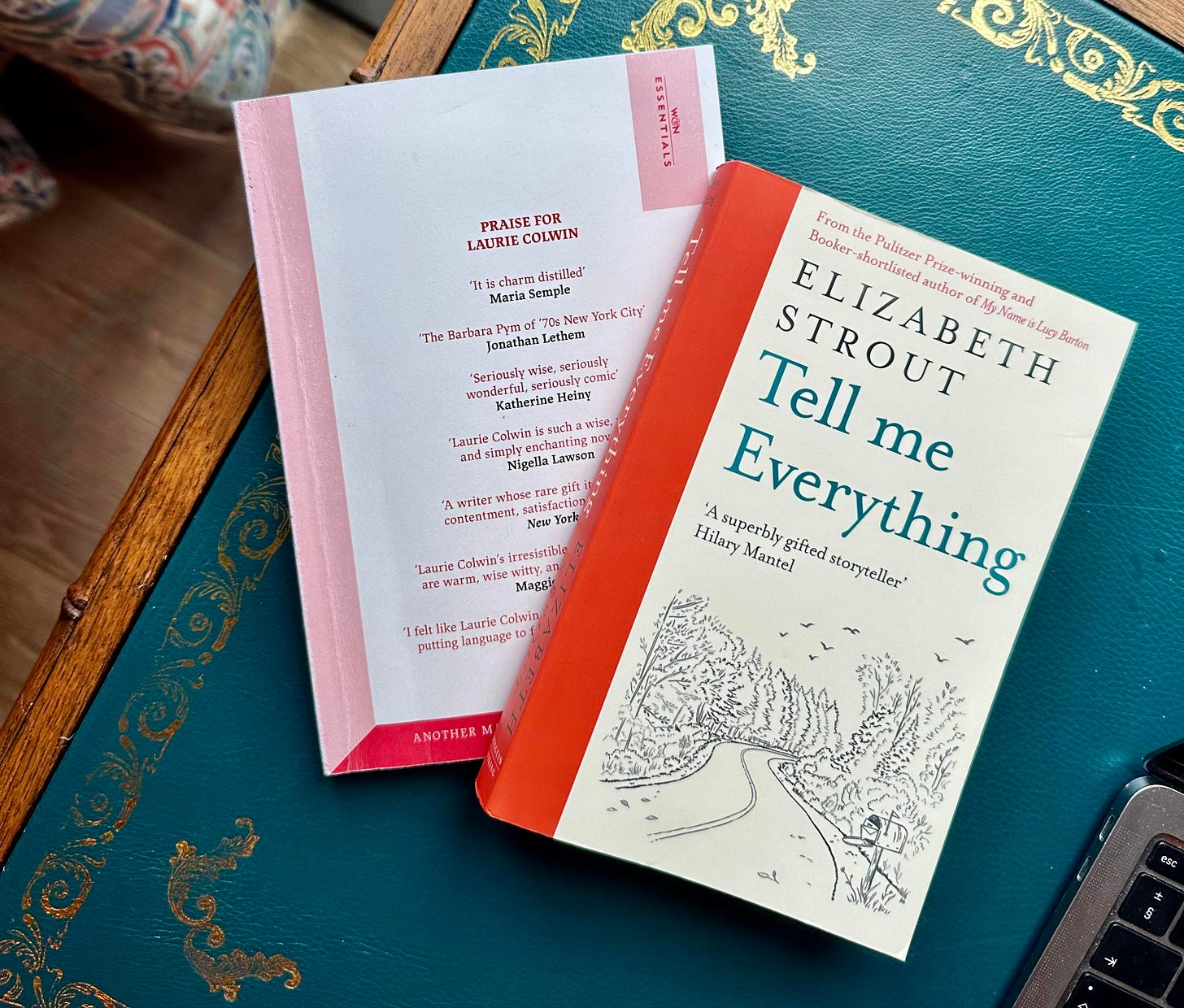

Either way, there’s no real reason to marry Elizabeth Strout and Laurie Colwin - there’s 12 years between them and I’m not aware they ever knew each other - other than the fact their books make me feel the same way. And, of course, they both have new books out. Colwin died in 1992, so Another Marvellous Thing is a re-issue by W&N, while Tell Me Everything is a new book by Elizabeth Strout featuring my homegirl, Olive Kitteridge, as irascible and skewedly insightful as ever.

Back to that feeling, for a minute, because it’s not something I write about - or even think about, when I’m reading - but it very much factors into the process of reading and the way in which I choose what to read, and when. It’s amorphous, free of language really, a bodily sensation that can make one reading experience entirely different to the next, bound only by the fact that I am holding a book and my eyes are the portal with which I receive the information. But otherwise, the feeling you get reading one book from the next can be as different as eating a ham sandwich, to riding a rollercoaster.

When I read a book which is jaggedly written, ominous, perhaps quite alien to my life experience, I will feel jittery, on edge, like I’ve had too much sugar and the only way to make the feeling go away is to eat more of it. And then sometimes, a book makes me feel like I am lying in a small fishing boat with my mother, on a loch in Scotland, as the waves gently rock us to and fro. It doesn’t mean that the book is free of challenge, or enquiry - there are distinct pangs of tenderness, sadness, pathos, revelation - but I feel so taken care of by the author, that there are no alarming jags. It’s a particular quality, so hard to create, hard to even describe, as I’ve said, but I think it’s the secret to Elizabeth Strout’s success in particular.

This is why Colwin and Kitteridge sit together, today. They are chroniclers of intimacy, of people living cheek by jowl, of morning noon and night. They are interested in the human and the humdrum and in lives lived on the social fringes: where there is poverty, and shame, and quiet truth.

First to Colwin, whose fans include Nigella Lawson, Ann Patchett and Katherine Heiny, and who died in 1992, at the age of 48. (It devastates me anew, every time I remember. She had so much life to live, a child to raise and, I’m sure, so many more great books to write.) I am new-ish to Colwin - this is only the second book I’ve read by her, after reading Home Cooking the summer before last, for an episode of Book Chat - and I’m so pleased that W&N re-issued this very slim book - almost a novella, really, at 125 pages - because this is so different to Home Cooking.

Well, obviously, because it’s fiction this time, and there are no recipes, or talk of food. But also because this is sharper, spikier, it challenges the reader to care about two people having an affair, who also happen to be happily married. Colwin is at careful pains to make this clear - that they aren’t miserable, or on the cusp of divorce. They just happen to be in love with two people. (Despite the subject matter, reading it, I still have that calm sensation. I know I am in capable hands, and that even if everything is not going to turn out well, then I’ll be alright.)

Francis is in his 50s, debonair, mild-mannered, living a well-oiled, moderately luxurious life in New York City. He is “avowedly urban”, “beautifully dressed” and “not entirely a stranger to adulterous love”. Billy, by contrast, is a moody, scruffy, brilliant economic historian in her 30s, married to her childhood sweetheart, Grey. Francis and Billy are, on the surface, a mismatch. Not just in looks, but in terms of what they go for in a person. Francis is too smooth and shiny for Billy. Billy is too shabby and contemptuous for Francis. He calls her a “slob” and she calls him, “an old hetero”. And yet, as these things often go, their attraction is electric.

I’ve never read someone write about an affair the way Colwin does. The clarity is almost cleansing. The facts of their affair are simple, at least to Francis:

“I call her every morning. I see her almost every weekday afternoon. On the days she teaches, she calls. We are as faithful as the Canada goose, more or less. She is an absolute fact of my life. When not at work, and when not with her, my thoughts rest upon the subject of her as easily as you might lay a hand on a child’s head. I conduct a mental life with her when we are apart. Thinking about her is like entering a secret room to which only I have access.”

Oh, the temerity of Colwin to write about an affair with such reverence! This is a lucid love, not clouded in shame (at least until later in the book). There is an almost child-like purity to it, which exists, of course, because it is a story only two people are telling to one another. Colwin does not judge her two characters, she inserts no moral opinion whatsoever, does not try and explain away or rationalise their decision. Notes Lisa Zeidner:

“An unusual aspect of a Colwin courtship is how confident the women are about their attractions, how frankly and unapologetically libidinous”.

Francis is violently curious about Billy’s husband, Grey, while Billy cuts Francis dead if he so much as mentions Vera. It is an altogether easier affair for Francis (him having had extra-marital relationships before, his feeling like he is in a new season of his life), whereas it causes Billy great angst. The angst comes from knowing that this is temporary. They are not building a life together.

“If her own case had been presented to her she would have dismissed it as messy uneccessary, and somewhat sordid, but when she fell in love she fell as if backward into a swimming pool.”

They are not planning an escape. There is no game plan, no end note. Muses Francis:

Were we to cohabit, I believe I would be driven nuts and she would come to loathe me. My household is well run and well regulated. I like routine and I like things to go along smoothly… I asked myself, as I am always asking myself: could I exist in some ugly flat with my cheerless mistress? I could not, as my mistress is always the first to point out… “Face it,” said my tireless mistress. “We have no raison d’être. There is no disputing this.”.

It’s also very funny, incase that isn’t evident by now.

I don’t think it’s any great spoiler to say that Billy and Francis do not end up together. The most affecting part, for me, comes after they have split (which they do well before the end of the book), when they have become memories to one another - they bump into each other, and Billy’s life has changed much more than Francis’s, and he is somehow shocked by the facts of this, as if he never imagined that Billy’s life could change this way once he left it; that she might want for things that she had not told him she wanted for. He realises, with not a small amount of pain, that he only ever knew a very small part of her. It’s probably the biggest takeaway of the book: that we can only ever know the parts of someone, that they are willing to show.

To Strout, who is one of our most important living authors today, beloved by Zadie Smith, Maggie O’Farrell and Hilary Mantel, they themselves bedrocks of contemporary literature. There are a few things happening in Tell Me Everything, which will thrill long-time readers, because it combines her beloved characters Lucy Barton (who Strout has written five books on) and Olive Kitteridge (the subject of two.)

Historically, I have preferred the Olive Kitteridge books to the Lucy Barton ones. I fear this is the last book that Olive Kitteridge will feature in, because Olive is now very, very old and living in a care home. And yet still she has that gimlet gaze, streaks of cruelty and a bone-deep care for community. This is a huge part of Strout’s books: they are powered by a sort of Dickensian social conscience, and she uses Olive and Lucy as vehicles to tell stories about people who have been forgotten, or dismissed. They function as a reminder that community can be built by anyone, in any place, and not least through storytelling.

Which of course is where Lucy Barton comes in. Lucy, by narrative chance, is now living in Crosby, Maine, near Olive. She is a successful writer but, as Olive is disappointed to discover, a rather quiet, self-effacing character. She does not carry herself with the deportment Olive hoped, when she called her into the care home, to tell her stories she wants recalled, remembered, written down. (It is as if she knows that she does not have much time left and so she must export these stories, while she still can.)

Lucy, to her credit, does not question why she has given up her time to visit a woman she does not know, who is frequently rude to her, as if knowing that Olive is encouraging Lucy herself to probe more deeply into her stories, her thoughts. In turn, Lucy encourages a famously rigid Olive to expand her definitions of what people can and can’t be.

And then it came to Olive; she had an understanding. She said, “Lucy, you’re a lonely little thing.”

Lucy looked up at her quickly. She said, “Who is not lonely, Olive? Show me one person.”

Olive said, “Plenty of people. All the snot-wots who lice here and gather every day in the lounge for their glass of wine with each other. They’re not lonely.”

“How do you know?” Lucy bit on her lower lip and then she said, “How do you know what those people think about in the dark when they wake up in the middle of the night?”

Olive had no answer for her.

Lucy has gone to see Olive because Bob Burgess has asked her to visit. Bob and Lucy play an important part in each other’s lives: they have met at a time when they are both feeling particularly introspective, a little haunted, still happily-ish married (as readers of Oh, William! will know) but feeling alone as they segue out of middle-age into old(er) age. Bob, a local lawyer, has been called out of semi-retirement to help investigate the death of an older woman, who lived with her adult son, who is a social recluse. The police suspect that he had something to do with her death, but Bob isn’t so sure.

The murder investigation is one thread of the book, but it isn’t a whodunnit, really, it all folds into the same search for community, truth and being seen. Strout’s books are also concerned from growing older, wondering about your place in the world, your relevance, your responsibility, From Lucy’s conflicted feelings around her adult daughters - one of whom is recovering from PND - who no longer seem to need her, to her second time marriage to William, to Bob’s feelings about his troubled brother, a childhood trauma, his hugely capable wife (does she need him, does she want him), it all keys into the same set of desires, yearnings, grievances. And for Olive, life is now contained to a care home. When her friend Isabelle leaves, to go and live in California with her family, Olive writes her a note, almost child-like in its pain:

THERE ARE VERY FEW PEOPLE IN THE WORLD WE FEEL CONNECTED TO. I FEEL CONNECTED TO YOU. LOVE, OLIVE.

Something that always strikes me, reading Strout, is how unafraid of old age she is, and more politically, how determined she is to pay it attention to old age, rather than pretend people just stop existing after a certain age. Here’s a particularly tender passage, when Bob visits old Mrs Hasselback, which he does every Thursday to deliver her groceries.

She went into the bathroom and then found a magic marker in a drawer in the kitchen, and then she moved toward him and handed him what he thought at first was a small pile of rags. But they were her underpants. “Do you mind writing on the back of these a big B so that when I put them on I know which is the back and which is the front?”

So he took them, there were four pairs - a tremendously off-white color - of roundish underpants, and her finally found the labels, so worn they were hardly there on the back, and he too the magic marker and wore a larger B on each pair near the top. “there you go.” He handed them up to her where she stood over him, watching.

“Thank you, Robert,” she said. “I appreciate that. The pair I’m wearing right now you can do next week.”"

Don’t you just ache, reading that?

It’s a more gentle book than Colwin’s, which is something I sometimes struggle with - it’s why I don’t always gel with Ann Patchett and Ann Tyler, I just sometimes want a bit more oomph, a bit more revelation - but it’s also part of why Strout’s books remain calm, I think, rather than overtly sad. And for the most part, I love them. Strout writes about a lot of sad things, many of the stories Lucy and Olive tell each other are pretty depressing, of lives thwarted and lonely, but the feeling reading her book is of those calm, peaceable waters, where everything continues to flow, and the world continues to turn, no matter what’s happening in each of our very small, individual, but inter-connected lives.

If you haven’t yet read Laurie Colwin’s Goodbye Without Leaving, I highly recommend it. It has a similar clarity as Another Marvellous Thing.

"It’s amorphous, free of language really, a bodily sensation that can make one reading experience entirely different to the next, bound only by the fact that I am holding a book and my eyes are the portal with which I receive the information." WOW. Not only is this truly beautiful writing, but it so perfectly encapsulates how I too feel when devouring a delicious book.