I didn’t actually set out for these books to connect with one another — how I read is much more arbitrary than that — but when I sat down with this little pile, they felt like they had an obvious synergy. It might be because I’m seeking certain things from stories but I think it’s equally true that books on motherhood, grief and displacement (often at the same time) are being more readily published.

We Were The Universe by Kimberley King Parsons is about grief and desire and the demands of motherhood, which prevents our young protagonist from sliding into grief’s hallucinations and the drugs of her past. Kit is in her early 20s, living in Texas, married to her university boyfriend, Jad and parenting an almost 4-year old, Greta. (Yes, she snaps, before you can ask: she still breastfeeds Greta.) Getting pregnant whilst at university was unexpected, but (and this felt like a fresh spin), Kit’s marriage is not a prison, her daughter is not a burden. She finds freedom and sweetness in her tiny nuclear family and they feel like all she has to live for. Because before then, Kit was a sister — and now she is not. Her and her sister Julie (the title is the name of a band the teenage sisters once formed) were inseparable; bound by love and drugs, they raised one another.

“Julie and I mothered ourselves and each other for years, because we had to. Mama tried, like the song says. She had her moments. She loved our problems, our unbearable teenage sadness. Of the teacher who singled me out for chewing gum in class: “Fuck her,” Mum said. “No law against gum… Girls who were mean to us: “They should all be murdered,” said Mom”.

The way King Parsons writes about this specific sort of maternal abandonment — a mother there, but not there — is exquisite and shattering. (Indeed, it informs Kit’s own attachment parenting; her unwillingness to leave Greta for a second, even at night.) Later, Kit recalls a time when Julie was 13 and she was 15, and they went to the petrol station, with their mother dozing in the car. Thinking they were runaways, a swarm of old men approached the girls, trying to sell the them drugs and buy them booze.

“In the car we told Mom what happened and she said she was proud of us — we were women now, and politely refusing men was what being a woman was all about. She said we should try to remember that this kind of attention was a good thing, that the men who wanted to fuck us could keep us safe from the men who wanted to hurt us…. What if they’re the exact same men? I wanted to ask.”

The book explores the spectrum of grief with a breadth I am not sure I’ve seen rendered in fiction before. Kit is ashamed of Julie’s death, while her mother — a drinker, a hoarder, on the brink of eviction — feels humiliated by her loss. On Jad’s encouragement, Kit goes to a retreat for the weekend with her heartbroken best friend, Pete, a wellness enthusiast in searching of healing. Pete says he can’t wait to unplug from work (and Grindr). For Kit:

“I’m plugged into nothing. I have no deadlines, no personal ambition, no professional goals of any kind. I’m dedicated to aimlessness and my adorable, needy family. Pinning Gilda down, brushing her tiny teeth, slicking her hair into disobedient pigtails.”

The first two lines of that paragraph could have been lifted from a great many works of contemporary fiction featuring young women in their mid-twenties, disillusioned, full of ennui — but the last two, revealing a toddler, reveal a different kind of book. In that sense, We Were The Universe reminded me more of Margo’s Got Money Troubles (which is also about resilience, poverty and inter-generational motherhood.) There is the same sweetness that never quite tips into sentimentality, the same pragmatism and lack of self-pity, the same almost psychic connection to breastmilk. On motherhood, the book is incredibly funny and tender: King Parsons takes children — their wants, their needs, their thoughts — seriously. (As Bobby observed in our most recent episode of Book Chat, this is something Kiley Reid does very well in Such A Fun Age.)

One of the most affecting parts of the book is when Kit lies about who she is to a glamorous stranger she desires, a mother of five boys who she meets on the park bench in the playground. She tells this woman that she doesn’t have any children, that Greta is her niece, who she looks after because her sister is messed up. Later on, she finds out this woman does not have five sons — she is a drug dealer, spinning stories that she hopes might charm Kit into buying her drugs. Jad is horrified — there’s a woman pushing drugs in the sandpit? — but Kit is shocked for a different reason: she can’t believe this woman lied to her. She thought she was the one doing the lying.

Kit feels the same kind of psychic pull that the narrator experiences in All Fours, the same desperation to feel body-rooted — “I thought that getting pregnant might bring me to the corporeal, but no. Instead, I felt the body within my body — Gilda flipping around, a life inside the weird, loose sock of me” — but the place Kit yearns for is not a re-decorated motel room in middle America, it is a place where her either grief has left, or her sister has returned to: a place between reality and fantasy. “Desolation. Some murky fate, waiting for us.”

We Were The Universe shares many of the same themes as Miranda July’s critically acclaimed novel - motherhood, grief, lust (it’s not quite as horny as All Fours but there’s still a lot of desperate masturbating) and an intense awareness of the shimmering precarity of life — with some key differences: Kit is half the age of July’s protagonist and does not have the same financial privilege and creative success — as Kit herself notes drily, “there’s always been a tremendous gulf between my taste, which is excellent, and my ability, which is nonexistent” — and she’s also wading through grief. But the two novels pulse with a similar irreverence.

Which got me thinking about why it is that some books find soaring commercial success and others remain very quietly brilliant. Partly, it’s because All Fours hit a particular nerve (expanding mainstream discourse around menopause and monogamy in thrilling new ways) but partly it’s because of publicity, if the author is well known, and happenstance. I loved We Were The Universe as much as I loved All Fours. But it doesn’t look like the former got any critical attention in the UK when it came out last summer. I want to change that. So get your peepers on it, stat!

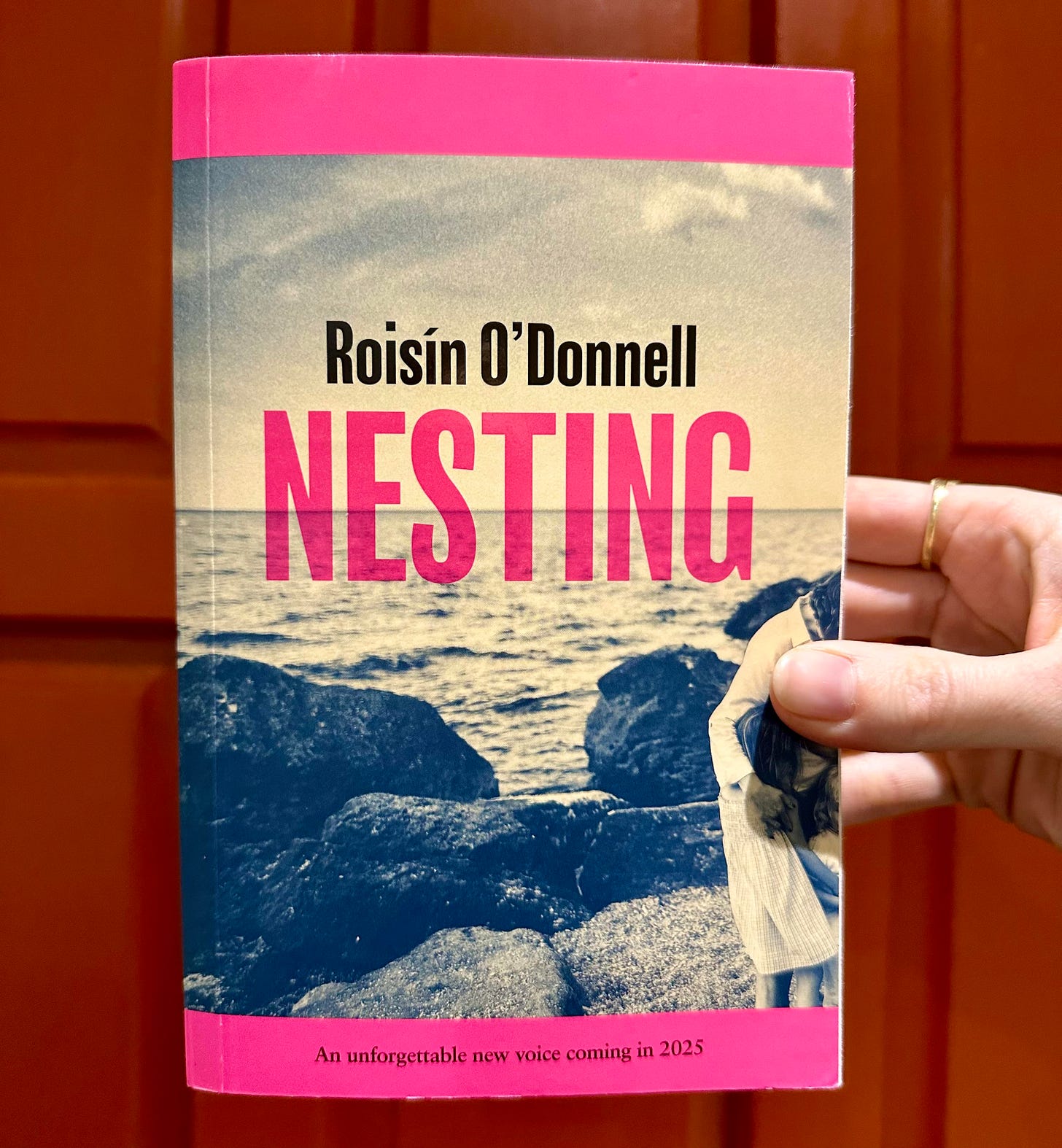

Nesting is not a book that shimmers, but it thrums with a tense energy. The prose isn’t lyrical or yearning, which is all the better to let this stark, urgent story reveal itself. It is a political book, simply told and devastating to read, about intimate partner violence and Ireland’s broken housing system.

When Chiara, a mother of two young children living in Ireland, realises that she is pregnant for the third time, she knows she must leave her husband. Ryan emotionally, financially and sexually abuses his wife. Chiara has no money of her own (he counts out every single penny for every single purchase) and no friends and Ryan “does things at night” that she can’t possibly square with the “love you babe” thrown over his shoulder as he leaves the house each morning. Chiara’s mother and her sister — loving, worried sick — beg her to leave him and come to them in Sheffield, like she once did before, like she’s tried to do on so many occasions. But Ryan put a hold on their passports. If Chiara leaves the country with her children, she will be charged with kidnapping. And so with just £80 stored in a nappy, she makes a run for it, seeking emergency shelter. But that doesn’t mean Ryan is out of her life. How can he be, when she has no money, no support and — newly pregnant, desperate to shield her baby from his father’s fury — too terrified to tell anyone the truth?

Being housed in a hotel (which functions as emergency accommodation in Ireland’s housing crisis) is a relief for Chiara, but O’Donnell meticulously illustrates the daily humiliations involved: tenants have to use a different entrance to the hotel guests, aren’t allowed in the shared areas (which means that entire families are confined to one bedroom) and have to to present themselves at reception at 7pm every single day, or face eviction. I found myself holding my breath, shoulders bunched up, every time Chiara — held up by yet another senseless piece of red tape — found herself sprinting to make curfew.

“She looks down the endless corridor. Mottled red carpet blotted with stains. Scratched walls. The stench of cheap industrial disinfectant. Sepia prints of colonial-era Dublin. Ryan’s voice in her head. For no reason. You are tearing this family apart for no reason at all. [Chiara] says, ‘I don’t know if I should have left. He didn’t cheat, or drink, or gamble. And it wasn’t physical. He didn’t hit me or anything.’ [Replies her neighbour, Cathy] ‘Your husband didn’t hit you? Well that was very fuckin nice of him. Make sure you text and say thanks… Look, you didn’t bring your kids to live in a hotel for no reason. These fuckers fairly screw with your head.”

Then there’s the absence of childcare. How are you meant to work, when the emergency accommodation has no childcare? And if you cannot work, you don’t have any money, for food, for clothes. So how do you prove to the state — when your husband deliberately never leaves a mark on you and complains to child services that you are deliberately keeping your children in poverty — that your children are better off with you?

In her acknowledgements, O’Donnell notes that she drew on a paper by Dr. Melanie Nowicki, ‘The Hotelisation of the Housing Crisis’ and I suspect that this might be the first time that many readers read about homeless families being placed in hotels, as a means of temporary accommodation. Certainly, it’s the first novel I have read about it. In many cases, it’s not even particularly temporary: some of Chiara’s neighbours have been in the hotel for years, waiting for a council house to become free. O’Donnell meticulously lays out the vicious cycle of poverty and abuse that many of the hotel’s residents have experienced. But at the same time, the author is careful to show that poverty is not the thing that might trap a woman in an abusive relationship. Through her next-door-neighbour at the hotel, Chiara meets a young mother called Alex, whose husband is immensely wealthy and well-known. Alex leaves, and then she returns; she leaves, and then she returns. It is so much harder to leave than to stay.

When I read Meena Kandasamy’s work of auto-fiction When I Hit You in 2019, I was disabused of some of my naivety around emotional abuse and coercive behaviour, which was that surely everyone would understand when you left an abusive partner. That is not always the case. Ryan’s mother is vile to Chiara, furious that she is depriving her son of his children, while simultaneously berating her for expecting Ryan to have them overnight on his own, or provide any kind of child support. It is a stark and necessary reminder that there are still plenty of people who believe that a martial vow comes above female safety.

The book is intensely stressful in subject matter, but the prose is calm, as if to emphasise that this isn’t melodrama, this is real life, for many people. The gravity never slows it down — it clips along almost like a thriller — with the novel’s momentum comes from Chiara, an extraordinarily resilient, compassionate woman, who will do anything to keep her children safe.

Hanako Footman’s debut, Mongrel is about three young women of Japanese descent: Mei, growing up in Surrey in a white family, disconnected from her Japanese heritage after her mother died when she was young; Yuki, who leaves rural Japan for England aged 18, to study as a concert violinist, before becoming pregnant by her much older teacher; and Haruka, working as a hostess at a sex club in Tokyo, grieving her mother and longing for information about her long lost sister.

The women’s stories are kept separate, told in their own alternating chapters, and it isn’t until the final third of the book that the narrative threads tie up — although cleverer reader may clock how the women relate to one another earlier than me. The book’s themes of displacement, grief and motherhood are most aptly explored in Yuki. Barely into her 20s, raising a toddler, she longs for the Japanese countryside, but knows she cannot go back — her parents saw her decision to stay in London and have a baby with an English man as a rejection. Yuki’s loneliness is compounded by the fact that she speaks little English, a fact that she suspects may have initially endeared her to her husband, Alex.

“He talks to her as if English is her mother tongue,

Maybe he uses this to his advantage.

When she is older and alone, she will think,

(Maybe when words failed me, he used the silence to touch me.

Maybe that is all he wanted.

A silent girl with worship in her eyes.)”

(It reminds me in these moments of Katherine Min’s The Fetishist, a sexy, spiky book I absolutely loved, where an older, white music teacher suffers the consequences for lusting after his young, Asian students.) Desperately lonely and suspecting Alex of a wandering eye, Yuki grieves her ambition, her culture, her childhood. She pours all of her longing into her little girl, Meiko.

Mei has not lived in Japan since she was very young, but she feels desperately lonely in Surrey, with her father’s white, wealthy friends, who make comments about how she has “a bit of the Orient in her”. She lusts for her best friend, Fran, but does she wants to be with Fran, or be Fran —white, confident, thrilled to take up space? When a sexual assault unmoors Mei further, she becomes an almost spectral presence in her own life, worrying her concerned father and her accomplished, overbearing step-mother. But what if her step-mother is not the villain? What if her father is at the root of Mei’s displacement? (It would be a spoiler to write more — but this was the most compelling part of the book for me and heart-breaking.)

Haruka’s story is the least fleshed out, or perhaps it just feels like that because it starts a little later in the book. Haruka is an orphan, raised by grandparents whose grief prevents them from telling her anything about her mother, or the sister she never knew. Her grandfather, Jiji:

“[B]lames himself for Mama’s death… Haruka knew that every glimpse of his daughter’s worn slippers felt like another death for Jiji.”

Footman is an actor, who grew up in “white, affluent, Wimbledon”, struggling to reconcile the whiteness of her world with the fact that her mother — and her life at home — was Japanese. After being told she didn’t look Japanese ‘enough’ to be cast in ESEA roles, she poured the years of microaggressions into a script, which later became a novel. I longed for a few moments of levity in the book, but Footman’s prose has some beautiful turns — Mei is “between the stretch of thirteen and the ache of fourteen” — and is at times, refreshingly sharp — Yuki cannot bring herself to eat the ongiri and tamago-yaki that Mama prepared for her flight because, “she cannot eat her home. If she does, all that will be left will be within, slowly turning to shit”. The great wells of feeling and attention to detail reminded me of Coco Mellors. If you liked Blue Sisters, I think you’ll like this.

I can highly recommend a book by a Vietnamese Australian author Tracey Lien. Her book is "All that's left unsaid". I couldn't put this book down.

This is the only other post I've seen here about Mongrel, and I'm so glad you love it too.