I’ve mentioned several times on this letter that I don’t go in for ‘beach reads’, or any seasonally-specific books for that matter. (I draw the line at wearing Christmas pyjamas out of season. Just wrong.) But I find that all I want to read this summer are richly peopled, chonky novels that don’t require much brain power. That’s not to say these books are bimbos—quite the opposite, in fact. It means that they do the hard work for you. The large cast of characters are well-formed, the book tightly edited (I keep reading proofs which are 200 pages too long), the dialogue is just the right amount (not verbose, not mute) the prose smart and witty and the plots so excellently plotted, that I can just lie back and be swept away on a tide of authorial competence.

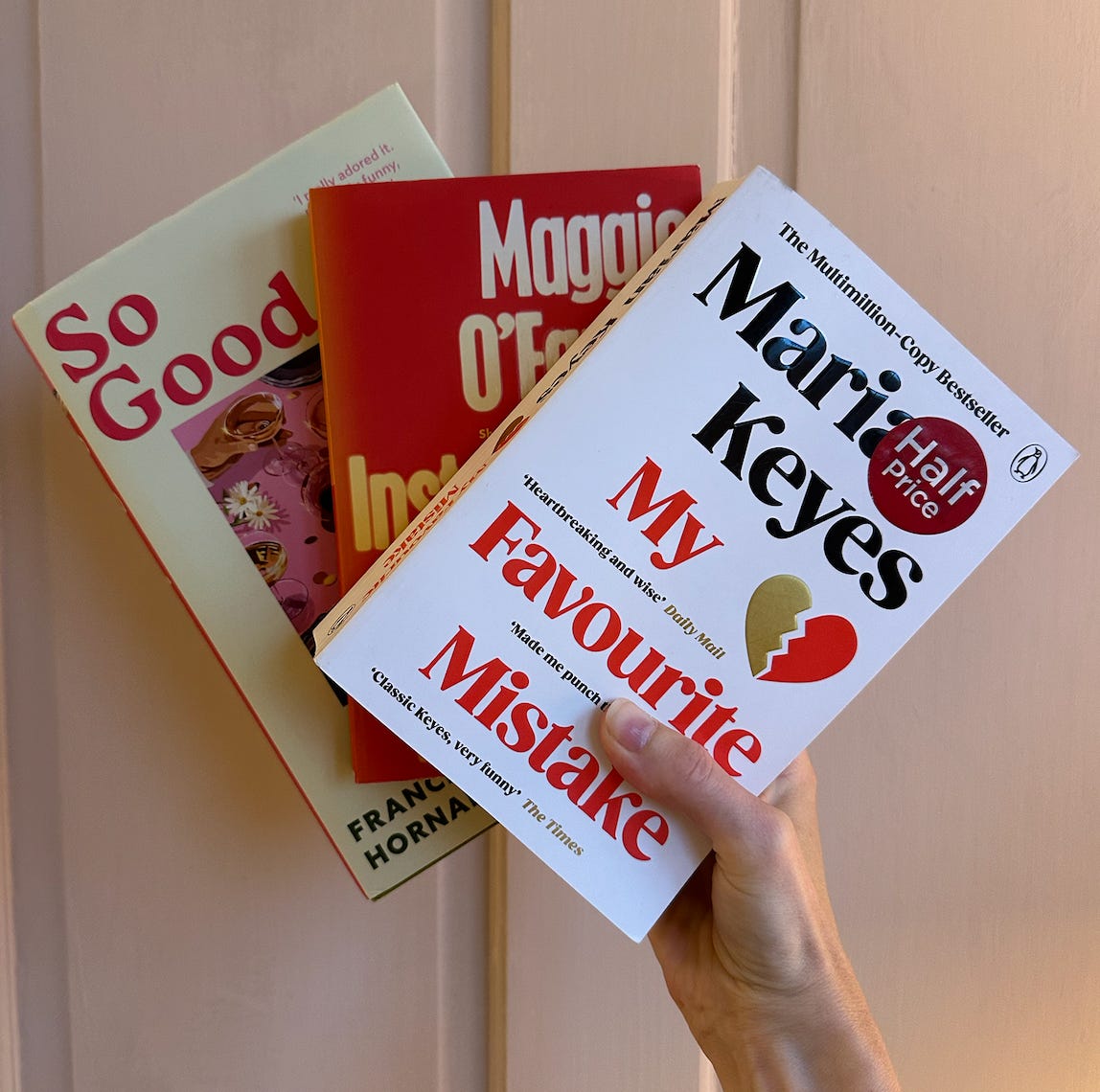

This trio of books are about coming back together after a rupture. You can’t go wrong with a good reunion and these three novels offer literary kintsugi of the best kind. In Instructions for a Heatwave, three disparate siblings are drawn back to the family home when their father goes missing. In So Good To See You, a group of once close university friends are forced to confront their grievances over a hot August weekend. In My Favourite Mistake, broken bonds between former friends and lovers are soldered. I’m often asked for books with happy endings and so for those who asked, here are three. In the words of Sticky Fingers (note that I have borrowed the lyric but not the behaviours of): happy endings are for those who wait.

Smooth that bewildered brow: Maggie O’Farrell’s sixth novel was indeed written in 2013. I’m trying to widen my reading beyond proofs (or as the Americans call them, arcs). At some point or another I fell into a hole with this letter of thinking (assuming?) that you all want to know about new releases, but it doesn’t feel good to just be reading newness. So, going forward, I’m going to mix in some older titles with my book round-ups. The benefit of this is that you will be able to buy them in paperback, and second hand. (I got my copy of Instructions for a Heatwave for £1 off Vinted.)

I am one of those rare readers who has read two books by Maggie O’Farrell—and neither of them are The Marriage Portrait or Hamnet. (This is because I am adamant I don’t like hist fic. Bobby has convinced my to try Hamnet, though, so I’m taking it away next month.) I only recently read my first O’Farrell, for Book Chat. It was her debut, After You’d Gone, published when she was just 26, and I liked it; it was intensely moving, careful and clear, but also a little earnest. A bit dry, perhaps. Bobby marvelled at how different it was to The Marriage Portrait and Hamnet (both of which he has read and absolutely loved), which made me want to try another of her novels, to see what differences I might find, there, too. On the basis of eeny meeny miny moe, I picked Instructions for a Heatwave.

The book is set in July 1976, during London’s longest ever heatwave. (It was over 30 degrees for two months, people were encouraged to bathe with friends, and a Minister for Drought was appointed.) Strange things happen in heatwaves; the heat gets to our heads, our hearts, our loins. As O’Farrell puts it in her afterword, “people behave in the most erratic and eccentric ways.” And on one of these steaming cloudless days, Robert Riordan, who I’d estimate to be in his late fifties, nips out to the shops and never comes back. His wife Gretta calls her three children and summons them home for the search.

Once close, the siblings are now prickly with one another, each nursing private hurts and resentments. In family lore, Monica is the favourite, the middle child who could do no wrong, a prim Stepford Wife trying to bake her stepchildren into loving (or even liking) her. Michael Francis is the eldest, much put upon, a school teacher who married his teenage sweetheart and two children later, finds himself lonely and yearning. Aoife is the baby, fiercely intelligent but 'never quite right’, who ran away to New York three years ago after a bust-up with Monica.

The siblings are uniquely miserable but share similar short-cuts to joy, the kind of short-cuts forged long ago that can never be replicated outside of a family. Forced into reluctant reunion by Gretta, they must confront their different childhoods (same family, different childhood, it happens more than books give credit for) and thwarted ambitions and their forgotten, pain-filled Irish history. In order to find Robert, things that have never been spoken of must now be talked about.

I’m glad I tried another O’Farrell, despite being unsure of my first. I loved it! It has that same old-timey feel, that slight earnestness and that extremely clear attention to detail, but it’s funnier, slightly vibier, with unexpected details. The author takes the same polyphonic approach in this one as she does in her debut (this might be something she always does; if you’ve read all of her books, let me know), where she tells the story from multiple viewpoints, so that the same incident is turned over and over, and examined for fresh insight, like a Rubik’s cube. Sometimes this is done to comic effect: over the course of the book, each and every Riordan silently marvels at Michael Francis’s wife’s new haircut. I found it so keenly observed (feet are “sugared with sand”; Gretta’s mother’s clot on the brain is “a dark, ferric gathering of blood, like a snarl in a skein of yarn”) so moving, so clear and clean and satisfying to read.

I was particularly moved by Aoife’s severe dyslexia, which makes her illiterate. Reading it now you can instantly tell why she can’t read, but in the 70s the understanding of dyslexia was limited, and so Aoife, despite being fiercely intelligent (speaking in long sentences at the age of 2), is kept down year after year after year, until she is towering over the infants in reception. She leaves school without a single qualification. Now, in her 30s, no-one knows that she cannot read. She has developed tricks and defences and routes to muddle through, but she is constantly terrified that people will find out, that she will get fired, or dumped, or sent back to England. It’s heart-breaking to read, knowing how easy it would be for her to access help now.

I was also struck by Gretta’s reflections of motherhood when your children are all grown: that a family home will always be a family home, even when the children are no longer children and have left. It made me think about how much my relationship with parenthood, my children, my home, will evolve in years to come; how this intensely felt part of parenthood that I am in right now, when my children are so close to me—physically and psychically—will only last so long. In a few short years I will, as Michael Francis observes of his wife, be visible in my “astonishing separateness”.

“The house is full of ghosts for Gretta. If she looks quickly into the garden, she is sure she can see the ribcage of the old wooden climbing frame that Michael Francis fell off and broke his front tooth. She could go downstairs now and see the pegs in the hall full of school satchels, gym bags, Michael Francis’s rugby kit. She could turn a corner and find her son lying on his stomach on the landing, reading a comic, or baby Aoife hauling herself up the stairs, determined to join her siblings, or Monica learning to make scrambled eggs for the first time. The air, for Gretta, still rings with their cries, their squabbles, their triumphs, their small griefs. She cannot believe that time of life is over. For her it all happened and is still happening and will happen forever.”

It all happened and is still happening and will happen forever.

There’s nothing like reading a book about a holiday in a place that you are also going on holiday—if you are going to the south east of France this summer, Francesca Hornak’s second novel, So Good To See You, is a packing essential. The French part isn’t mandatory, mind. If fun, pacy and beautifully written books about dysfunctional families, complicated friendships and a wedding where it all comes apart are your SPF of choice (of course they are), then you should take it too.

Tension is all around when former university friends Serge, Rosie and Daniel are brought back together for their mutual friend Caspar’s wedding in Provence. Rosie must let Caspar know if she will carry a baby for him and his soon-to-be husband—and she can’t make up her mind. At the same time, she’s busily showing her ex, Serge, that she’s not at all heartbroken. Easier said that done when he turns up with his beautiful bohemian wife, Isla, and their adorable toddler twins. A cult film director, everyone thinks that charming, handsome Serge is winning at life. It’s a facade he deliberately maintains. In truth, it’s a sham—things are strained with Isla and he is deep in debt. He’s also nervous about seeing Daniel, his best friend and writing partner at university, now distant and chippy. Daniel’s a successful Hollywood actor, but he’s dealing with a family of demons: he’s wildly homesick in LA, addicted to drugs and alcohol and secretly maintaining a troll account on Twitter. He’s filled with rage towards Serge, who went off and made their film without him. But again (and this says something about masculinity, I think), he commits to the bit.

“Caspar enquired after Daniel’s love life, and he told Caspar about a date with a barista and how they had gatecrashed an A-lister’s pool party. The original anecdote had been hugely embellished, but he had told is so often it had come to feel like a memory. He had never called the barista and now he had to patronise a different coffee shop. Los Angeles was full of bars he had to avoid for this reason.”

The secondary characters are naturally less fleshed out than the main players, but all have their own heartbreaks and peccadilloes: Allegra, glamorous and showy but painfully thin and vulnerable; Isla, seemingly carefree, but feeling desperately out of place and lonely, trapped in an exhausting loop of twin toddlerhood.

Hornak’s writing is sharp and satisfying. It reminds me a lot of Elizabeth Day’s in The Party. But it’s also got the tenderness of David Nicholls, the dryness of Nick Hornby. It’s very British, basically. Serge is strongly remeniscient of Dexter in One Day, and the homage to Nicholls feels intentional: one character observes that Rosie wanted to get together with Serge, her handsome best friend from uni, because it would be like One Day. The reader’s sympathies will likely lie with Rosie, the unofficial main character, who tries so hard to “morph… laughing excessively and suppressing any opinions”, to smoothe and smile and people please. Underneath the perky edifice, though, she’s broken and baffled at how life has turned out, how her solid, enviable friendship group has just shattered. She is steeped in nostalgia for a period of life that everyone else has so cleanly left behind.

“They still had all their noughties memories of Neighbours and taramasalata and Diesel jeans, and all the printed photographs - their faces luminously young.”

The book is set over one long weekend, but it winds back to the grievances and pinch points of twenty years ago, the tiny hinge moments that shape you as adults. For instance, Serge’s sister Allegra’s severe anorexia is shown to have come from one fleeting moment, when she was just 17, when Serge’s friend pushed her off his lap—because she was drunk and young and it felt inappropriate for him to entertain her (in short, he was doing the right thing)—but it leaves Allegra with the impression that she was too heavy to be kissed, held, loved. Rosie, meanwhile, has spent two decades pretending she is at ease in a world she does not understand. But she is baffled by the impossibly distinct layers of wealth, the references “to the Bloomsbury set”. Hornak is a brilliant chronicles of class and social mores, and all the lubrication that is necessary at one single wedding.

“Serge was still staring at her, incredulous and offended, so [Rosie] said, ‘Enjoy your night,’ and walked away towards the marquee. She could not return to Nate and his friends, now. The glamour of being angry, of expressing herself like Isla, had been a chimera. All she had achieved was losing the grace and dignity she had worked so hard to preserve. She was not like Isla. She could not navigate conflict. And she wished she had not used pubic hair to make a point.”

I love how Hornak’s writing switches gears so effortlessly. There’s catharsis—“the laughter rinsed through [Isla], and she felt something loosen that had been knotted for months”; wit—Imogen’s baby starts crying, “its head poking out of the sling like an angry tortoise”; and crisis—”He was the most absurd and laughable kind of man. He felt deeply homesick, a yearning like grief.” There’s something so pleasing about reading something where you are in no doubt as to what’s going on; the author isn’t trying to trip you up or confuse you. That’s not to say that sometimes I don’t like a slippery book which unmoors me, but it is to say that reading books where you are so safe in the writer’s hands that you feel like this (unequivocally my favourite of my daughter’s teddies) is divine.

Somehow a new Marian Keyes came out last year, and I only just learned of it— I spotted it on my mother’s bedside a few weekends ago, and stole it immediately. (Poor woman, she’d only read 50 pages.) (She told me I could borrow it, practically forced it into my greedy hands.) But then, it sort of tracks, because I was miraculously late to Marian Keyes to begin with. I only read my first Keyes 6 years ago, when pregnant with my older son. I was on holiday with some friends and found Rachel’s Holiday on my friend’s bookshelf (my favourite place to find books are on other people’s bookshelves, I’d never heard of Meg Wolitzer until I found a battered copy of The Interestings on a bookshelf in Costa Rica on my honeymoon a decade ago). I guzzled the whole thing, in raptures. I’ve since read two more of the seven ‘Walsh books’ (Keyes’s series of novels about five Irish sisters) and not in the right order. I’m planning to fill in my blanks, pronto.

In My Favourite Mistake, the sisters range from late 30s to early 50s and in my head I have ascribed them each a character from Bad Sisters. For the first time in 25 years, they are all back together living in Ireland. The Walsh books centre on a different sister in each book (Rachel’s had two, this is Anna’s second, Claire, Helen and Margaret have had one each) and this one is a sequel, told from Anna’s perspective. The first, Anybody Out There was published 20 years ago. Having amicably broken up with her boyfriend of ten years, Anna, a senior beauty PR, has realised that it is time for a do-over. To her family’s horror (they love free beauty loot/ they don’t want to have to babysit her because she’s got no friends in Ireland), Anna announces that she’s quitting the beauty industry and coming home.

And yet, for all their grumblings, the Walshes are of course thrilled to have Anna back. Everyone, that is, except Joey: the ex of her former best friend, Jacqui, who also happens to be the on/off love of Anna’s love. Anna and Joey fell out in New York, around the same time Anna and Jacqui fell out. We don’t know why, except that it caused Anna tremendous pain. But then Anna and Joey end up working together. Will either of them let their guard down?

I can’t stress this enough: Marian Keyes is a genius. Clearly, I am not alone in thinking this, as she’s sold 35 million books. She has also spoken numerous times about how men are lauded for writing about the domestic and the familial and women are not. “Just because something is positive or uplifting doesn’t mean that it doesn’t have depth or seriousness” she said in conversation with Curtis Sittenfeld for The Irish Times, last year. “I think a lot of people might have trouble grasping that; that if there is a love story that’s central to the novel, it doesn’t mean silliness or disconnection from real life.”

I have been lucky enough to meet Keyes several times and she herself is a sprite, gimlet-eyed and feverishly witty, but not afraid to be deeply truthful—she wrote a beautiful essay for What Writers Read about reading Stella Gibbons’s Cold Comfort Farm when she was suicidal and struggling with addiction. She’s not afraid of going deep, but her self-deprecating, kooky humour is the best thing about the Walsh books. For instance, men who are in touch with their feelings are called “feathery strokers”; they are mocked by the sisters for being very earnest and spiritual (they might get a feather out any moment and start running it down your spine) but they also tend be the nicest men and so more than one of the Walsh sisters must admit to her sisters that it’s true, she has fallen for a feathery stroker.

And then there are all these delightful decades-long habits and jokes that pop up in multiple books, like easter eggs: Rachel’s husband Luke wears such tight trousers that all the Walsh women have to fan themselves after seeing him; it is a known fact that Rachel will always be late, because Rachel and Luke are always shagging; despite being the oldest and the most laden with children, Claire is the horniest sister, although their mother trails very closely behind. It is another unspoken rule that like Mr Bennett, Mr Walsh must never be troubled with emotional things. It makes him quite scared, he must be protected from these six feminine energies. But in all honesty, he isn’t really needed. The Walsh world is a woman’s world.

The sisters rile each other up like nobody’s business, they don’t ever press the real bruises and they do everything they can to keep each other’s tender spots covered. It’s really galvanizing to read and itt models sisterhood: that it is possible to rage against each other and be ruthlessly truthful but also care for each other fiercely and consistently, accepting a sister for exactly who she is. I love how they’re all breathless every time a hot man comes by (yet at the same time, they will let hot men go if they do not serve them), that they travel as a pack, that there are two child-free Walsh sisters and their lives are treated with the same nuance and curiosity as the three with children, and that the lives of the sisters with children are also treated with nuance: they aren’t just mothers, and the children aren’t just snivelling rotters.

As the sisters get older, so do the themes of the books. Where once the books focused on fertility and ambivalence around motherhood, now it is the menopause, specifically “menopause deniers”. Anna is shocked to find that hormone replacement therapy is infinitely more elusive in Ireland than in New York—and highly politicised. Keyes is making a point about the geo-politics of medicine and how misunderstood the symptoms of menopause are. “Menopause is not an illness. HRT is not a medicine”, intones one young Irish doctor to Anna. “So why do I have to see a doctor to get it?” Anna retorts. “It made my life worth living”. The doctor relents and writes her a prescription, but not before “shaking her head in performative disbelief.” As Keyes put it in an interview with Annie Mac for her podcast, Changes:

“The doctors in Ireland are not as, how would you call it, generous with the prescriptions as they are in the US, where I think their prescription writing is inspired by Tolstoy.”

There has been a small backlash to The Menopause Conversation (as always happens when an overdue thing is unlocked from its secret box and gathers something of a momentum, there have been a swathe of books and pods about it in the last few years) and what Keyes does so well in My Favourite Mistake is to explore it with a lightness of touch: as soon as Anna takes her HRT she is DTF. Her libido comes roaring back and she is terrified at where the horn might take her.

If you’re wrung dry by life, this is the book to take on holiday. You can thank me afterwards. Bonne vacances!

I seem to be the exception here. In September 1998, I walked in to the classroom for my first GCSE English lesson to the sight of a poster for Rachel’s Holiday on the wall. Along with two friends, I was so drawn to the bright pink cover that we bought a copy between us and devoured it. We went on to buy Watermelon and Lucy Sullivan is Getting Married, and followed this up by writing a letter to Marian Keyes who very kindly replied in purple pen.

Come November 1999, at the grand age of 15 we tottered along to her book tour for Last Chance Saloon. I can still remember the grey Kookaï suit and silver Faith court shoes I wore- we felt so grown up! Marian was a delight in person, told everyone else at the reading how we’d written to her and afterwards she sent another letter and arranged for her publisher to send us some posters.

26 years later my framed Last Chance Saloon poster still hangs on the wall of my office. It reminds me of my two teenage friends who now live abroad, and despite losing touch it encapsulates the joy of the friendship that burned bright and of the shared nights out and formative experiences.

As for Marian Keyes, it has delighted me how much success she has gone on to have. Whenever I hear her interviewed, she seems to remain the kind and genuine person who humoured three teenage girls when she was starting out despite how she has publicly talked about her struggles with depression. I always look forward to her new releases and as I’ve aged, I only have more and more admiration and appreciation for how an author labelled ‘chick lit’ has shown her writing is so much more than that misogynistic label.

If you haven’t read a Marian Keyes, perhaps start Rachel’s Holiday and then go back and do them in order. I am very jealous that you have a whole 16 books to devour.

This is the email I needed in my inbox this morning. It’s increasingly difficult to read anything with a grim ending given everything that is happening.

And to have an unread Maggie O’Farrell in it - hurrah!

Through this excerpt brought tears to my eyes. “It all happened and is still happening and will happen forever”.

‘This must be the place’ takes a similar approach in telling the same story from a few angles. Which can really be so devastating when you understand how characters fail to reach out to each other and communicate what they need.

But really consuming writing. Really enjoy her books and looking forward to this one.