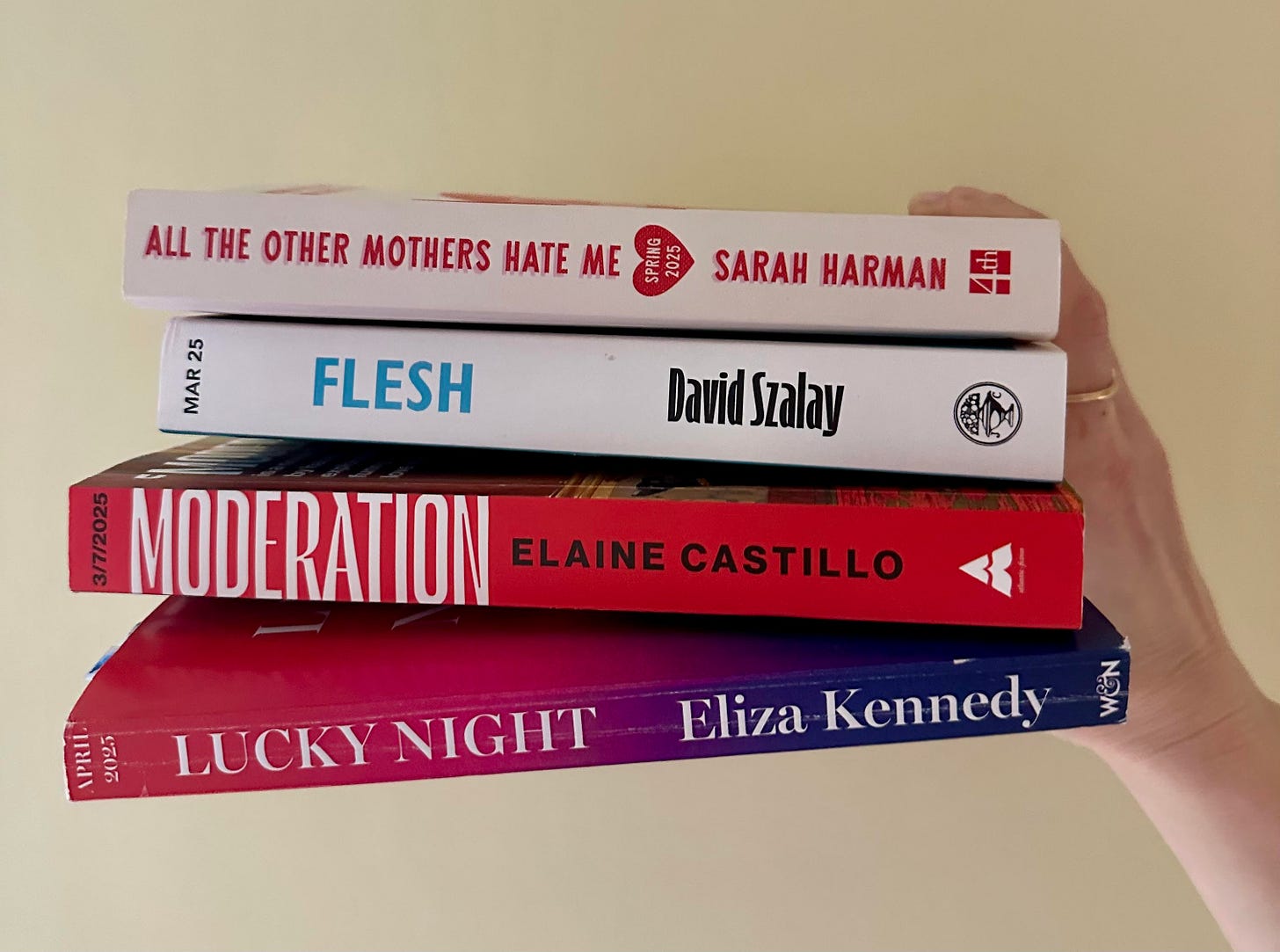

Four novels for spring

Rejoice! Two of my favourite writers, Elaine Castillo and David Szalay, have new novels out

I’d usually run Book Chat this Tuesday but Bobby and his toddler have been taken down by a long and nasty virus, so we are postponing our podcast about Anna Karenina until next month. Ngl, while I’ve been pleasantly surprised by my first Tolstoy, I will not be cracking the spine on another 800+ page book anytime soon. You know that rhyme, “There was an old woman who lived in a shoe. She had so many children, she didn't know what to do”? That’s how I felt about all the books I wasn’t reading while I was wading through Levin’s farm for one million hours.

On to today’s letter, about a bunch of new novels landing for spring. And none over 400 pages, hurrah!

All The Other Mothers Hate Me by Sarah Harman (out on Thursday)

A ridiculously fun title (eliciting a smirk from anyone with school-aged kids) nodding to the trope explored in Motherland/ the latest Bridget Jones film, which is that the rivalry at the school gates is fiercer than anything you might find in finance. But our protagonist Florence—sharp, steely, cynical—is no Amanda, or Perfect Nicolette. She couldn’t give a toss if the mums at the school gates give her the stink-eye.

A 31-year-old broke former popstar (in a girlband called Girls Night, lol) and a single mother to the “occasionally eccentric” Dylan, 10, Florence runs a party balloon business in West London and rotates a series of casual relationships with excruciating men, purely for the fancy dinners. Matt B (not to be confused with Matt T) is described as:

“[A] Deutsche Bank currency trader whose entire personality is going for sashimi at dimly lit Mayfair restaurants… Matt B thinks I don’t know he has a wife and three kids stashed away at his five-bed suburban home in Oxfordshire, but I do. I just really like good sushi.”

To the distaste of the other mothers, Florence openly refuses to perform motherhood, yearning for the glamour and excitement and wealth of her younger years. This would be fertile enough ground, but then Alfie, Dylan’s classmate, a horrible little boy and heir to a fish finger fortune, goes missing on a school trip—and Dylan is the prime suspect.

All The Other Mothers Hate Me is a caper which I can easily imagine as a TV show (unsurprisingly, Harman, who describes herself as a ‘recovering journalist’, is currently adapting it for FX/ Disney+, with The Bear’s Christopher Storer attached). It’s ostensibly a thriller, but (thankfully, as I don’t dig thrillers) I found it to be more of a compelling vehicle through which to challenge the assumed qualities of a mother: maternal, caring, soft, vulnerable.

Florence loves Dylan —he is “the best thing in [Florence’s] life, without exception”—but she hates the repetitive, conventional drudgery of being a mother: school drop-offs and cooking tea and forms and uniforms and playdates. She is, however, determined to find Alfie and clear Dylan’s name. Because Dylan—her sweet, perfect boy—can’t possibly be guilty, can he. Can he?

Flesh by David Szalay (out now)

David Szalay is the author of one of my favourite short story collections, All That Man Is—which is technically a novel and which Bobby and I spoke about last year for Book Chat—and I’m really excited to be interviewing him and Natasha Brown, at The Charleston Literary Festival next month. His fifth novel, Flesh, is Szalay (pronounced Solloy) at his most Szalayist. By which I mean, it is a brutal, unvarnished story of an unexceptional man buffeted by other’s people’s choices. It is a book about wealth, sex and power and it is hard to describe without making it sound exceptionally unlovely—but then, it is the unloveliness that makes this novel so compelling.

Flesh tells the life story of István, who we meet as a diffident, monosyllabic 15-year-old, living on a housing estate in Hungary, with his mother. One day his mother tells him that he is to help the lady across the hall with her shopping twice a week. He is unmoved by his neighbour—she is 42 to his 15, he doesn’t find her attractive, they hardly talk—but when she initiates a sexual affair, he complies without much thought. She is his formative sexual experience (a clear abuse of power) and he decides he must be in love with her; but when he tells her, she tells him that they must never speak again. While trying to get her to speak to him one day, he ends up knocking her older husband down the stairs. It could be an accident, we aren’t sure. István is sent to a youth penitentiary. This is clearly a defining chapter of a young boy’s life, but István doesn’t reflect upon it—nor, indeed anything, that happens to him.

“To the extent that he thinks about it at all, [István] thinks of the job at the winery as a very temporary thing, something he will do for a few months maybe, just until he finds something else.

Except that he isn’t actually trying to find anything else.

It’s like he’s waiting for something else to find him. Or not even that. He isn’t really thinking about the future at all.”

It isn’t until he joins the army and witnesses a friend dying, that István acknowledges that any sort of trauma. It is dealt with briskly, and on István goes to London, where he works as a bouncer on the door of a strip club. One day, he saves a man’s life and the man offers him a job, in private security. Which is how István ends up working for a very wealthy and uncharming couple, with one son. He has an affair with the nanny (“it just sort of happens”) which he is unbothered about when it ends, as much as he is unbothered by everything.

“He enjoyed his night with the Canadian nanny. He doesn’t feel that it was a mistake himself. He would have been okay with seeing her again, if she wanted to. That she doesn’t want to is okay too. He has this feeling with women, that it’s hard to have an experience that feels entirely new, that doesn’t feel like something that has already happen, and will probably happen again in some very similar way, so that it never feels like all that much is at stake.”

Soon enough (we have to assume that István’s reticence translates to women as appealingly brooding) his boss’s wife, Helen, seduces him—and, well, I won’t give away the series of events that follows, except to say that István’s ascent is extraordinary and he witnesses it all from the outside, almost in retrospect, even as it’s happening.

Flesh is a melancholy story of hardship, if the musicality of melancholy had been scraped off. It is simple, brutal and devastatingly effective, with dialogue pared right back to the bone—the title, I take, as irony. There is no flesh here, no fat whatsoever. It is very very occasionally tender and when it is tender—such as István’s relationship with his young son—it is fucking heart-breaking. It sat with me afterwards in much the same way Stoner sat with me—a book of everything and nothing, a sad story of a less than vivid man—but there is a sharpness to it, that makes you flinch.

Szalay’s work is often described as being about modern masculinity and to be fair, All That Man is starts with a short story about an adolescent male and ends with a man in his 80s. But to me, his books read more as a questioning of agency, in that how much agency could any man have, whilst also being open to the vicissitudes of fate? If he has wealth, he has power—as István briefly experiences—but even then, that wealth, that power, that control, is merciless and illusive. An alternative title could be, Is This All That Life Is? It’s not a comforting proposition, but Szalay isn’t interested in comfort. He’s interested in the desires that punctuate the pulse of life. They pulse, they pulse, they pulse—and then they, and we, are gone.

Moderation by Elaine Castillo (I thought this was out in May, but I’ve just seen it’s July! Apologies, I usually time my dispatches better)

Castillo’s debut, America Is Not The Heart, about a Filipino-American family living in San Francisco, is one of my favourite novels I’ve read in the last few years. Her book of essays, which followed a year later, was a mixed bag: the titular essay on how not to read was excellent (although I’d have loved a more reparative one to end the book, like how to read), whilst the one on the Austrian writer Handke went rather over my head. Nevertheless, I gasped in glee when her second novel, Moderation, landed on my doormat. (Great cover, great title.) Castillo is a literary firecracker, a public intellectual, a lively and droll interviewee. If you haven’t yet engaged with her work, now is your chance.

Thirty-something Girlie—smart, jaded, operating on very efficient autopilot—and her extended family live in a strange and ornate home in Las Vegas, after being priced out of their home in Milpitas (where Castillo’s debut is also set) in San Francisco. There is something of a double dislocation, with the first generation of Girlie’s family yearning for the Philippines and the second gen yearning for the Bay area. No-one, to be clear, wants to be in Vegas.

“If someone had told Girlie when she was a kid that Milpitas would one day be gentrified; if someone had told her that the town that famously smelled of shit and had the best Southeast Asian food in the Bay and whose contours would remain as known and loved to her as the body of any lovers, would one day demand over a million dollars for a newly built townhouse out in the weedy backlots south of the mall, she would have—laughed, probably. Died, maybe. Asked what alternative universe they’d come from. But she didn’t know yet that there were thousands upon thousands of universes crumped up like a bad draft in God’s back pocket; that it is easy to tumble out of one and into another.”

Girlie works as a content moderator, flagging the internet’s most violent and depraved content. It’s brutal work, which most people fail at, but which Girlie takes seriously and dispassionately, mostly because it is well-paid. And then Girlie is head-hunted to moderate a VR theme park. She will exist within the game: lush worlds that have been built with such skill that she can feel the wind in her hair, taste food, smell the woods. She will move between these worlds, logging inappropriate behaviour.

But the worlds are too convincing. It is hard for Girlie to hold on to her dispassion: to resist the kindly wisdom of the doctor working alongside her, who knows VR could alleviate her trauma; to remain impervious to the mysterious allure of her British-Chinese boss, William, who took over the company after his best friend’s untimely death from a high rise building. Girlie’s defences are crumbling, leaving her terrifyingly vulnerable.

This is a compelling plot, and the writing—as typical for Castillo—is tenacious and nimble. Reading her is like pressing your finger on a bruise just to feel the thrill: “rich fifty was working-class thirty-five”… “beauty made people stupid: neurologically, historically, globally.” Castillo is clearly fascinated by VR—it’s medical benefits, its impossible feats of beauty, its moral quandaries—and it tips a little too far, I think, into the technical weeds of virtual reality and content moderation. But I’d recommend it on the strength of Castillo’s characters and social observation. If you liked Gabrielle Zevin’s Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and/or The Circle by Dave Eggers, you’ll like this.

Lucky Night by Eliza Kennedy (out 17th April)

This is a fun book, set over one night. Nick (46, partner in a law firm) and Jenny (40, hugely successful novelist), together for 6 years, are on a fancy mini break in New York City, when their hotel sets on fire. Being inside a building that is on fire would be stressful enough, but Nick and Jenny have an added layer of anxiety to contend with: they both have spouses, who they will now have to call, to explain why they are holed up in a hotel room in a burning building that they are about to see on the news, with someone else.

Lucky Night is like an onion of conceits. The first is the obvious: will Nick and Jenny have to tell their partners that they are having an affair? The second is more subtle: they genuinely adore their partners, and claim not to be in love with one another, so why have they been maintaining an affair for over half a decade? The third layer to be peeled away is intriguing, shape-shifting: who holds the power? Is it Nick, who has never admitted to Jenny that he has read one of her books; or is it Jenny, who has never told Nick that for a brief period of time when they started their affair, she was in love with him? As the fire licks up the building, Nick and Jenny are forced into a reckoning. Who are they, to each other? Why have they stayed together for so long? And—the clincher—are they getting out of this alive?

Over the course of the novel, Kennedy explores Nick and Jenny’s determination not to capitulate to one another: it is a relationship rooted in sex, and ego and the total denial of vulnerability. There is no ‘real life’; their relationship exists entirely in fancy hotels every other week. Nick—‘horny’, ‘profane’ and ‘caustic’—pretends to Jenny that he’s never read her novels. (He has.) Jenny—’wonderfully unselfconscious’ with a ‘weary sexiness’—pretends she’s faked orgasms with him before (She hasn’t.)

“[Jenny] does lie to [Nick] from time to time. Whether she’s eaten at a particular restaurant, read a particular book. She’s knocked a couple of years off her age, too. Stupid stuff, but crucial. Because she realised, around year two, that he couldn’t be the only person she tells the truth to. If she’s going to betray everyone she loves, she can’t not betray him. That would be fatal.”

It is a smart, sly and satisfying book, which slides down easy as pie. I hate the term ‘beach reads’ but it would be great for a holiday, or plane—it’s so deft and well-written that it can be enjoyed with minimal effort on the reader’s part. It reminded me of Laurie Colwin, who writes about women who have affairs despite being very much in love with their husbands. It’s refreshing, in its more complicated version of adultery, as not just something terrible people do, not just something miserable people do. Kennedy examines her characters and their motivations throughly, holding them up to the light and turning them round and round until their most vulnerable parts have been exposed to one another, and us. As for whether they make it out alive—well, you’ll have to read the book.

I’ve read so many good books coming out this Spring, that there will be another one of these round-ups dropping very soon! In the meantime, what have you been reading lately? Do you have any recs for me? I’m always keen to add to my towering pile(s), so let me know in the Comments.

You know I love these posts. super excited for moderation and Lucky Night. I love a good literary affair.

i’m currently reading real americans by rachel khong, such beautiful prose and so engrossing! i think you’d love it, pandora! it recently came out in paperback here in the us!