I’m currently on a train back home, after moderating a panel at Leeds International Festival of Ideas on how reality TV distorts reality. My guests were: Rylan - reality TV contestant turned reality TV host (amongst many other jobs); Dr Charlotte Armitage - lead psychologist on Big Brother who has consulted on dozens of reality shows and true crime docs; Jazz Boatswain - a content creator who took part in everyone’s favourite gameshow, Traitors; and Prof Tim Wilson, who has possibly the most varied CV of anyone I’ve ever influenced - a monk, a politician, a professor in Russia - and was on catfishing reality show, The Circle. We had a blast.

I haven’t been back to Leeds since I left university 15 years ago and the prestalgia (not a word, should be) was strong before I arrived. Ironically, when I got there, I couldn’t get my bearings at all - not unusual for me, I have no internal compass, but I sent a video from my hotel window to my friend who also went to uni there and she said “you’re not in Leeds” - and so the nostalgia itself never really arrived. I wanted to see if I could get a guest pass to the Brotherton Library, which is this very grand, beautiful library which I loved working in, but sadly it was shut by the time I finished. I always hoped that I might pick up a hot nerd in the medieval literature aisle, like they do in Gossip Girl/ You/ every single show on Netflix, but alas, I remained resolutely single for my three years there.

Karen Russell’s 2005 short story for The New Yorker, ‘Haunting Olivia’ (which the magazine got author Louise Erdrich to read for their fiction podcast last month) is an absolutely stunning piece of writing. Brothers Timothy, 12, and Waldo, 14, are searching for their little sister, Olivia. She went missing when she was 8, after they left her alone crab-sledding into the sea - a winter spot on the rural Floridian island they live on, where giant crab shells are turned into sleds to skim down sand dunes. Days later, the empty crab shell was found half way to Cuba.

“I spend the next two hours pretending to look for Olivia. I shadow the spirit manatees, their backs scored with keloid stars from motorboat propellers. I somersault through stingrays. Bonefish flicker around me like mute banshees. I figure out how to braid the furry blue light of dead coral reef through my fingertips. I’ve started to enjoy myself, and I’ve nearly succeeded in exorcising Olivia from my thoughts, when a bunch of ghost shrimp materialize in front of my goggles, like a photo rinsed in a developing tray.”

Their parents have abandoned them to travel the world, leaving them with their brutal, toothless grandmother, who barely remembers her granddaughter and can’t understand why they are still looking for her. Of course, they aren’t really looking for Olivia - it’s more a psychic journey of guilt and grief, where they are looking for something tangible to end the not knowing. It’s lyrical, wrenching, unique and in parts, very funny. The best short story I’ve read in ages.

My life has been dramatically improved by Caitlin Reilly’s comedy - in particular, ‘Your Chronically Online Friend Who Is Severely Uninformed Shares Her Thoughts Again’. (The titles are so good.) It makes me laugh so much, it’s absolutely bang on.

It also has a more serious subtext, I think, which is that this modern demand to constantly externalise our views, is incredibly damaging. There are ways to support, to educate, to be educated, that have nothing to do with being online - and are often more valuable for it.

This is a smart bit of culture writing by Emma Specter, on the habitual thinness in Sally Rooney’s novels.

“There is, of course, no mandate that Rooney populates the landscape of her fiction with fat bodies as some kind of feint toward inclusion. But consider a reversal: if another writer, even one of Rooney’s stature, populated her novels with a similar number of fat characters, that stylistic choice would be interrogated in a way that Rooney’s is not. Rooney’s slim characters are able to detach from their bodies in ways that’s assumed fat people cannot, by sheer virtue of the fact that our physical forms have always connoted a lack of discipline that thin people are spared.”

Like the best bits of cultural criticism, it’s not a blast or a gotcha, it’s a thoughtful and well-researched piece of observational writing that asks both writer and reader to expand their ideas around femininity, vulnerability and intimacy.

An op-ed in response to the op-ed (I love this trend) arrives via New Zealand poet Hera Lindsay Bird’s defence of Rooney’s ‘skinny protagonists’ for The Spinoff. Bird doesn’t deny that Rooneypeople are slim, but that their bodies make sense in the narrative.

“For the vast majority of her novels, her characters wrestle with shame, self-hatred, issue of control and self-abnegation, a struggle which is reflected in their bodies and their diet… a spectre of deprivation haunts the early pages of her books.”

Of course Rooney has an aesthetic, says Bird, but so do most writers.

“Agatha Christie wrote the same book 66 times. Wodehouse wrote the same book over 90 times… Asking Sally Rooney not to write about a thin and damaged person who must find a way to relate to others in order to survive in the world is like asking Patricia Highsmith not to write about an attractive grifter with an eye for luxury and a magnetic core of emptiness at the pit of their soul.”

I’m reading Intermezzo at the moment and it hasn’t grabbed me by the throat yet. It might not? I’m sanguine either way. Not everything can be for everyone.

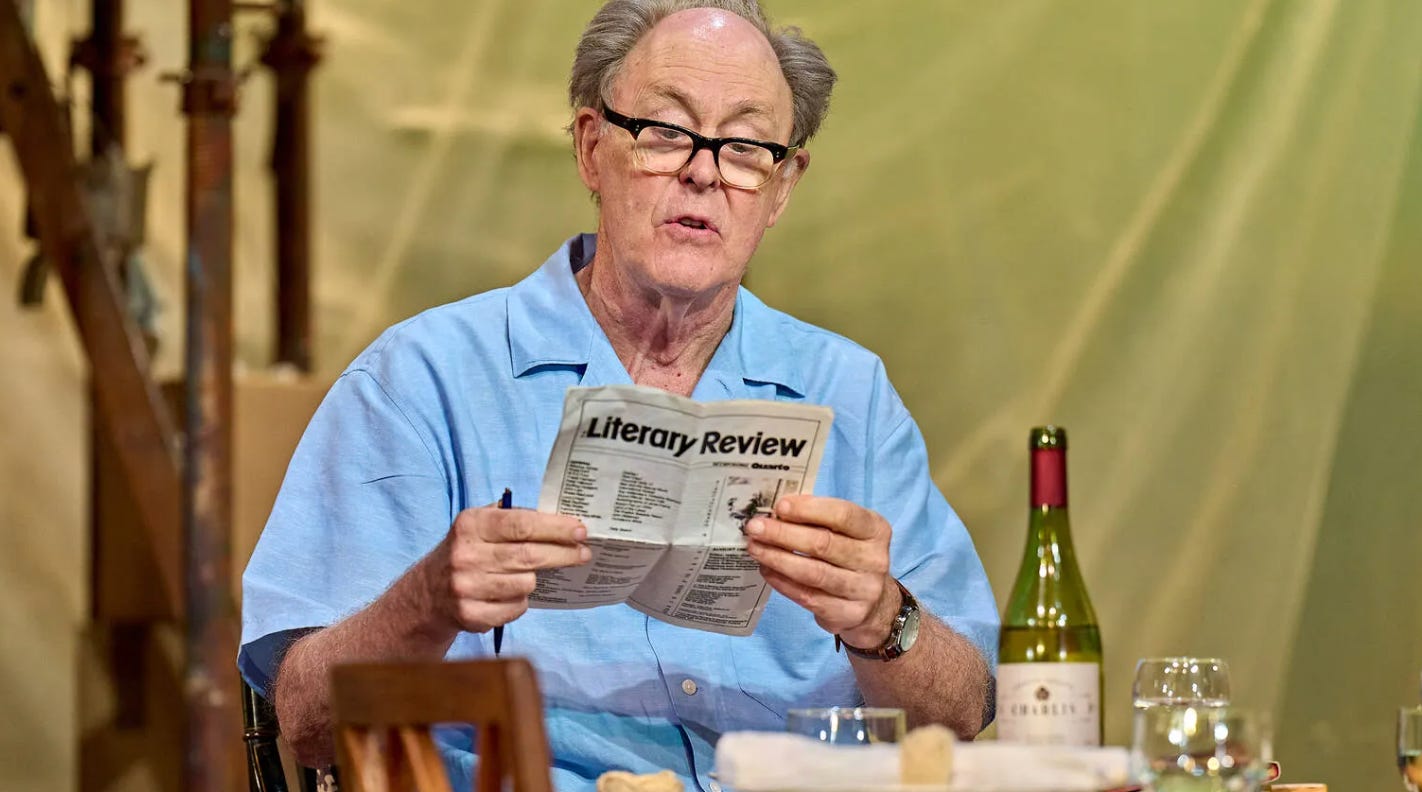

I was gutted to miss out on tickets to The Royal Court’s play about Roald Dahl, Giant, for which actor John Lithgow has received incredible critical reviews. I am fascinated by Dahl, not just for his books - Boy is one of my favourite books of all time, I think about Dahl’s nearly-severed nose, frequently - but by his biography (traumatic: he was packed off to boarding school shortly after his father and sister died; two of his children died in childhood) and his character (abusive, conflicted, famously anti-semitic). He was not a likeable man, and I found Lithgow talking about how he plays the author fascinating. When I realised the tickets were all sold out, I started noodling around the internet for Dahlian facts to fill the void.