Morning! I hope you’ve been enjoying some sunshine. August is finally Augusting.

This week I learned what a künstlerroman is. A subset of my good friend, the bildungsroman (the subject of my university dissertation) it is, according to the writer Hermione Hoby “a becoming an artist novel more than it is a mere coming of age story.” It’s also, notes Eric Somers, just “a good word. That’s all.” Calling someone a künstler also sounds like a deliciously baroque insult.

Speaking of niche nomenclature, I urgently need a name for an intense sensation that I experience not irregularly. That is: the moment you realise that you have eaten your last rolo/ hula hoop/ haribo, only after you have eaten it. It’s the deceit, when you realise too late to extend it the acknowledgement - the ceremony! - of being the last piece of snack, to save it, savour it, roll it between your fingers admiringly, etc. (It’s even worse when someone else does it. What a künstler.) It really deserves a properly name.

I adore this quote in the opening pages of Didion & Babitz, Lili Anolik’s forthcoming book about the epistolary relationship between the literary titans and frenemies, Joan Didion and Eve Babitz (“a complicated alliance, a friendship that went bad, amity turning to enmity”) in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Like something out of a movie, after Babitz’s death, her sister found a box of letters at the back of her closet and gave it to Anolik, who had spent years interviewing Babitz for a 2019 book. It always contains letters to other people, like this delicious morsel below.

An entire box of letters, from Joan Didion (elegant, curated, deliberately cold), to Eve Babitz (a hot mess, who used sex like a spoken language)? Epistolary gold. I’ll write more about it when it’s out in November. And, yes - Babitz is writing about gossip to the author of Catch 22. We contain multitudes!

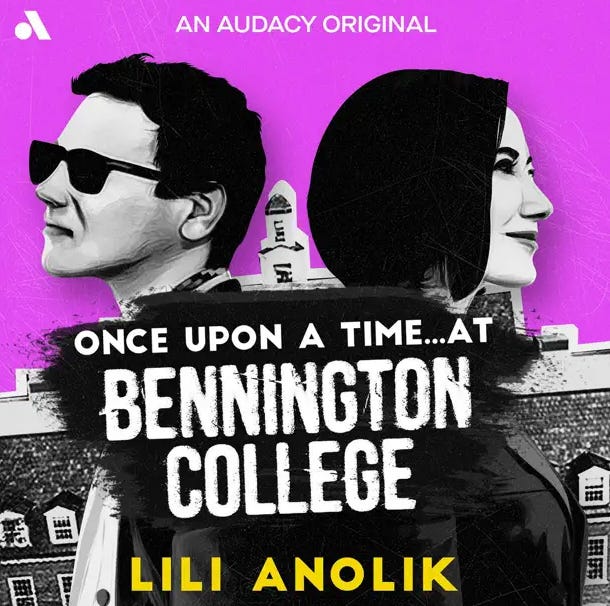

For now I recommend Anolik’s 2021 podcast, Once Upon A Time at Bennington College, about the most expensive university in America - a liberal arts college named Bennington, in Vermont - specifically, the class of ‘86, which included A Secret History’s Donna Tartt, and American Psycho’s Brett Easton Ellis. (The two are close - A Secret History is dedicated to Easton Ellis.)

It’s so atmospheric - about ‘80s (and ‘90s) LA, privilege, the arts, publishing, drugs. Easton Ellis contributes, which is admirable given that Anolik is far from flattering about him (whilst also reminding us that he was ahead of the zeitgeist and predicted the Trump era) but Tartt is not a fan - which I entirely understand. If someone said they were making a podcast about my university years (which they wouldn’t, because they’d have fuck all to write about) I’d be pretty freaked out, too.

In the streaming era, the celebrity documentary has swiftly become a keystone of a modern popstar’s offering - much like a skincare brand, or an Architectural Digest home tour. And so I’m not sure what I was expecting when I begun I Am: Celine Dion, but I don’t think I expected something so plain-speaking, so full of yearning. Partly this comes from Dion’s request that the documentary feature no talking heads (a gamble which pays off) and that the documentary was made by a filmmaker who has no interest in celebrity - and who approached this project like she would a humanitarian one.

Before she begun working on the film, director Irene Taylor had no idea that Dion was even sick - let alone that she had been chronically sick for 17 years. As is now common knowledge, Dion has Stiff Person Syndrome - a rare, neurological condition, which she says affects 1 in a million people and which saw her taking up to 90mg of Valium a day in order to be able to perform. The grief Dion feels for her former body is palpable.

The documentary was revelatory for that reason, but it was also refreshing for not once dwelling on the toxic side of fame. Typically - understandably! - a younger subject’s relationship with fame is at best ambivalent, at worst deeply traumatic and much of the documentary is spent discussing that. But Dion is a showman and misses performing - her fans, all of it - deep in her core.

Dion’s lack of conflict around fame is partly her personality, partly timing. She blew up when social media didn’t exist, when the ‘cult of personality’ was not so rapacious, when you could make mistakes. Sure, her showtunes in the 90s were marmitey, particularly when Titanic came out, but if she became famous, now, I think that the fact that she begun dating her manager (now late husband, who had been looking after her since she was 12) when she was 19 and he was 45, might cause such a ruckus, that her music might not have gotten the same traction.

The documentary’s strength is that it is not a film about an artist in her prime; it is a film about an artist ruing what she has lost. (The scene of her in a recording studio, after a two year break, sound technicians gently encouraging her as her once stupendous voice breaks, is so tender.) It’s the same quality that makes Pamela Anderson’s documentary so compelling: to see someone actually unvarnished (not just curatedly “I just woke up like this” Insta-bareface) looking back at their heyday, rather than being in the thick of it.

Taylor was told that nothing was off limits; she was free to record anything and everything, and so there is a deeply traumatic scene, where Dion experiences a seizure. Surrounded by superlative healthcare professionals, her hands gnarled and her face a mask of desperation, the tears flow down her face.

That said, there are still some delicious moments of diva. Her enormous house is a strange mix of shiny monochrome modernity and extraordinarily ornate Versaille-ish mirrors and frames. A piece of archive shows a a pregnant Dion surveying an enormous, immaculate closet full of flat shoes, before turning to her assistant and remarking tiredly that she doesn’t own a single flat shoe. In another scene, she walks around a vast aircraft hanger, where she stores all of her stage outfits, reminiscing about when she used to go designer shoe shopping. These moments add necessary lightness to the film.

In 2007, Carl Wilson wrote a popular book about his problem with Celine Dion’s sentimentality (he ended up becoming while not a fan, an admirer.) I Am: Celine Dion succeeds as a piece of art because it is harrowing and joyful, full of grief and longing - and unabashedly sentimental.

I Got Snipped: Notes after a Vasectomy in The Paris Review is the first thing I’ve read by Joseph Earl Thomas - and I am now desperate to read everything he’s written.