Are you reading? (Always.)

Are you lounging? (Not yet.)

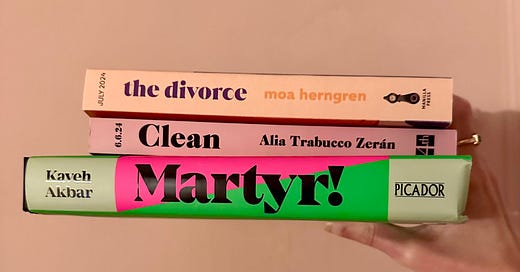

I had hoped to bring you an interview I’ve been working on, but it’s a sensitive subject and still needs a few checks. So for today, here’s a trio of books that I found thought provoking and jarring in totally different ways. I am desperate to talk about any/ all of them, so please do share your thoughts if you have any!

First up, we have The Divorce by Moa Herngren - translated from Swedish by Alice Menzies. Bea and Niklas have been married for over 30 years. But one day, after a trivial row, Niklas leaves their Stockholm home and says he is not coming back. To Bea’s horror, this seemingly small misunderstanding triggers the dissolution of her marriage. And before she has begun to even process the unravelling of their long partnership, Niklas begins another relationship.

Bea is utterly destabilised, while Niklas feels like he is finally able to breathe. And Bea must contend with the fact that it is not that Niklas did not want to be in a relationship, but that he no longer wanted to be in a relationship with her.

“There are moments when she really does wish that Niklas had just died. In some ways, that kind of grief would be far easier to handle. As it is, she is grieving someone who is very much alive, still living in the same neighbourhood.”

The writing is simple - basic, even - but what makes The Divorce so compelling is how Herngren explores the marital split from both sides, employing the same narrative trick as Taffy Brodesser-Akner in Fleishman Is In Trouble: the abandoned party tells their story, and then the defector gets to tell theirs. (I like that in The Divorce, Niklas and Bea are allocated the same amount of space to tell their stories. That said, that Toby gets four times as much time to rant in Fleishman as Rachel, is also the feminist point/ trojan horse of the book.)

It’s riveting as the reader to feel how your sympathies don’t so much shift, as flex, like a muscle, when the same story is told from the other point of view. There is no victim, no villain; just two people wanting - needing - entirely different things. Herngren elides the idea that every man who leaves his wife in his fifties must be a bastard, or having a breakdown. Niklas is allowed to seek joy and relief in his freedom, just as much as Bea is allowed to want permanence and control in her domesticity. (Although one is judged much more than the other.)

“[Niklas] just wants to feel his way back to himself. What else does he feel? What does he like? What doesn’t he like? It’s been so long since he really stopped to think about these things that he isn’t sure.”

Herngren is a former editor of Swedish Elle and a writer for the Netflix show Bonus Family and I imagine The Divorce might also be adapted into a TV series. Addictively readably and gently thought provoking, it would be useful for anyone going through a break-up (a reminder that there is always another version of the same story) or struggling to metabolise a relationship breakdown, but it’s also an interesting reminder for those in long-term partnerships, where family dynamics become fixed and roles can calcify. I found it a reminder to keep moving. To allow for evolutions, both great and small.

I follow a loose, not particularly intentional pattern with my reading, where I alternate easily satisfying books with ones designed to unsettle. They feel like necessary palate cleansers - or more accurately, palate agitators - that keep you on your toes and awaken you to something. Which brings me to one such novel, another book in translation - albeit sharper, bitter and socially minded: Clean, by Alia Trabucco Zerán (whose 2019, novel The Remainder, was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize) translated from Spanish by Sophie Hughes.

Clean opens much like Leïla Slimani’s harrowing Lullaby: a child has died and it is the nanny’s fault. And the nanny is telling us this nightmarish story - parsing out tidbits (“that’s enough for today”) - from the inside of a locked room. Who has locked her in there? How did the child die? But Clean is not a whodunnit, as much as it is a social critique wrapped up in a pseudo thriller: the thankless life of a low-paid, overworked domestic worker in Chile, underscored by social and political unrest.

Estela is a maid, cook and nanny for a doctor and a lawyer in Santiago and their young daughter, Julia. She describes the family as “an unhappy little girl, a woman keeping up appearances and a man keeping count: of every minute, every peso, every conquest.” She works 6 days a week, wears a starched uniform and is a mute presence (“I surrendered, voiceless, and eventually lost the desire to talk”) unless alone with Julia who she cares for diligently, if not lovingly.

“[My mama had told me] it would be difficult, almost impossible, to quit working as a maid. It’s a trap, she told me. You hang around waiting for a lucky break, and you secretly tell yourself: I’m leaving this week, next week for certain, next month will be my last here. And you just can’t, Lita, that’s what my mama warned me. You just can’t leave. You can’t ever say: Enough. You can’t say: No, I’ve had it, Señora, my back hurts, I’m leaving. It’s not like working in a shop or out in the fields or doing the potato harvest. It’s a job that’s kept out of sight… There’s no good loving your masters. They only love their own.”

When Julia says her first word “nana” (Estela’s name in the family) the señora tells her husband that she said “mama”. Estela witnesses the deceit, but the señora doesn’t care what Estela sees, because Estela has no voice. And even if she did, who would listen to her, the lowly help?

When a stray dog called Yany wanders into Estela’s life, the act of caregiving by choice, outside of her tiny domestic prison, triggers a quiet revolution in Estela - and a reckoning with her own freedom. But freedom comes at a cost. And when Julia learns of Yany’s existence, Estela, suddenley viciously furious, knows that her life is about to change forever.

“I hated that girl in that moment, and not only for her loose tongue. I hated how greedy she was. I hated her for wanting everything for herself.”

Clean does not offer answers - the political situation is sketched quite vaguely (I could not work out when it was set) and the pay-off is a touch dissatisfying. But it is a compelling book, with a tightly coiled power - with prose so taut, reading it feels like holding a cat’s cradle - about what it means to hold a family together, for years and years, with no rest, no reprieve, no affection. To witness vulgarity, cruelty and corporeal excess - as her bosses loudly have sex in the kitchen next to her bedroom - while she experiences no pleasure, no pain, no interior life.

Estela is not sentimental, and she isn’t going to tell you a bedtime story. She’s going to ask you to bear witness to a disturbing chapter. To hover in the discomfort. To see and not be seen. And then you can decide whether or not to unlock the door.

I’ve saved the most riotous till last: Martyr! the debut novel from the poet Kaveh Akbar. I bought this one based on the strength of the blurbs. When you’ve got Ann Patchett writing “it’s like watching the novel itself be reinvented”, you pick that shit up. The second reason it grabbed my attention is because of the title - how strange that exclamation mark is. How often do you see one in a title? How deliberate it is, how much it prepares you for the peculiar, stirring and bold novel that lies ahead.

Martyr! is about a young Iranian-American man called Cyrus Shams, a recovering addict and poet living in Idaho, who has felt lost and depressed for as long as he can remember. Instead of writing poetry, he earns a living as a “medical actor”, where he plays a dying patient or the family of a dying patient, for medical students to practise their pastoral care (I’d literally never heard of this job) and fixating on his mother’s senseless death, when her plane was shot out of the sky by the US Navy,as it flew over the Persian Gulf, in 1988 - a real life incident which America wrote off as an admin error.

Cyrus was just 10 weeks old when his mother, Roya, died. His shattered father Ali moves them both to Idaho, to work gruellingly long hours at an industrial chicken farm, while an insatiably insomniatic Cyrus never sleeps. Ali never recovers from the loss of Roya - “the anger felt ravenous, almost supernatural, like a dead dog hungry for its own bones” - and he dies after Cyrus graduates university, as if he was only holding on until Cyrus reached adulthood. Until Cyrus was okay.

But Cyrus is not okay. Now 29 years old, hanging on to his sobriety with gritted teeth, he is obsessed with finding meaning in death and martyrdom. (A brown man interested in martyrdom, he thinks wryly. That won’t scare anyone.) When he hears about a terminally ill Iranian-American artist, Orikdeh, performing a Marina Abramović-style death sit-in at the Brooklyn museum - where she will live in the museum and talk to visitors, right up until she dies - he decides he has at last found the meat of his story. With his best friend and sometime lover, Zee, Cyrus flies to New York to ask the dying about death.

Cyrus and Zee’s relationship is the quietest but tenderest part of the book, with Zee functioning not just as his sexual and linguistic sparring partner but as a preternaturally smart moral compass and beacon of hope. He is constantly reminding Cyrus to live his life here, now, not in the trauma of his family’s past in Iran, saying to him at one point: “You act like you live in this vacuum. Like there’s already this frame hanging around your life. But you can’t use history to rationalize everything”.

The conversations Cyrus and Orkideh have are short but profound. She tells him fascinating stories about Persian mirror art and when the Mona Lisa hung in Napoleon’s bedroom (tbf it’s Cyrus’s dream version of Orkideh that tells him that) and he buys her a cup of coffee when he visits, something he attributes to sonder (which is the revelation that everyone has the same complex inner lives as you do), before realising that it’s self-absorption not sonder that sees him, a fully grown man, congratulate himself for buying a dying artist a $2 coffee.

But Martyr! is not just Cyrus’s story. It is a polyphonic book, with chapters for Ali, Roya, and Arash - Roya’s brother, who served as a sort of death angel in the Iranian army, a grisly job where he rode amongst the battlefields of dying men, with a torch under his chin, to persuade them not to kill themselves but to die religiously - a job that gave him life-long PTSD, unable to work or leave his home.

“I am poor, unmarried. I didn’t finish high school… This means I am expandable, a “zero soldier.” Zero education, zero special skills, zero responsibility outside of my country. There is an expression. ‘If a zero soldier has to use a grenade to escape their life, they shouldn’t waste the grenade’."

It’s not a thriller, but there is a big twist: it makes sense, while being fairly unrealistic. And it totally changes Cyrus’s view of both his mother, and what a martyr really is.

Despite the book’s weighty subject matter, it is also very funny. Cyrus’s university girlfriend is described as being the kind of beautiful where “when they slept together, she would just kind of lie back and smile a little, like, ‘you’re welcome’.” On another occasion, when Zee bluntly tells Cyrus, “You just mope around not writing… You’re the definition of available”, another friend, Sad James, re-words it as “Flexible. You are currently open to the vicissitudes of fate.”

This is a book about trauma, grief, mental health, sexuality, addiction, art, language, death, race, male friendship, medicine, ambition, war, religion and masculinity. I actually can’t think of much it isn’t about. And sometimes it does feel like there’s too much crammed in - I could leave Cyrus’s dreams, charming as they are, where Cindy Crawford converses with Inspector Gadget, Kurt Cobain with Marie Curie, Rumi with Trump - but it still works in the main, this gorgeous, ambitious, riotous melting pot of a book, because of the novel’s unique conceit and the poetic electricity that zaps through it.

I guarantee you’ve never read anything like it. If prizes made sense (and they rarely do to me, and I say that as someone who has judged one!) then this debut would be on the next Booker list. I can’t wait for his next book.

I’ll be back on Friday with a batch of Bits. Have a good week!

Very keen to read the first one - I’ve had that exact thought (and a few friends have voiced it too) about how difficult it is to grieve a real person after a breakup compared to if they’ve died…

Also, thank you for always mentioning who the translator is! I work closely with literary translators and often their names aren’t even on the cover of the book, when they have spent many months immersed in the story they are translating and are bringing a huge part of themselves to it. A maybe interesting fact: in France, where I work, a literary translator is recognised as making deeply creative and personal choices when translating and as well as their fee for the translation, they also receive royalties from the translated book sales.

All of these books sound fascinating, thanks for sharing them. They are on my to read list!