2 Girls 1 Book: Sleep by Honor Jones

During a stifling summer at the apex of MeToo, one woman breaks free from her traumatic past

Welcome to the fifth edition of 2 Girls 1 Book, a monthly cross-post where Ochuko and Pandora chat about a new book via Google docs. This month we’re talking about Sleep, the debut novel from Honor Jones. As ever, we’d LOVE to hear from you in the Comments. And for those of you who like to read along, next month we will be reading The Emperor of Gladness by Ocean Vuong.

35-year-old Margaret is a new-ishly single mother of two young daughters, living in New York City. In her present, she is mothering, dating, navigating her pretentious ex, her cruel mother and a demanding job as a magazine editor. In her past, she is a little girl, being repeatedly molested over the course of several months, by her teenage brother. Suspended between the stifling summer of now and that of two decades ago, a reckoning forces its way through.

Pandora! For some reason it feels like such a long time since we did one of these. Probably because I’m in a completely different time zone now and I’ve barely read at all since our last book chat (massive reading slump). I read Sleep during my 9-hour flight from Germany to Portland. It was a surprisingly good travel companion and reminded me of a few books I’ve read in the past year. One that comes to mind immediately is The Paper Palace. Did you note that similarity?

That is exactly what it reminded me of. There’s an undeniable, synergy between them: childhood trauma, moneyed denial. I loved Paper Palace and I loved Sleep, too. I read it quite a while ago, so I re-read it this week in anticipation of our chat, and I was remembered again how well-written I think it is. How did you find it?

First of all, I love that phrase “moneyed denial.” Adding to my lexicon with immediate effect. I agree that it was so well-written. Something I’ve been trying to do recently with my reading is pay close attention to craft. The way the author built up these characters and played with language and pacing and setting—it was done with incredible skill. You know how at the beginning our protagonist is playing hide and seek under that blackberry bush? The whole novel had such a dreamlike quality that as a reader, it felt like I never quite got out from under that blackberry bush. Like, I was watching the whole thing unfold from some hidden vantage point.

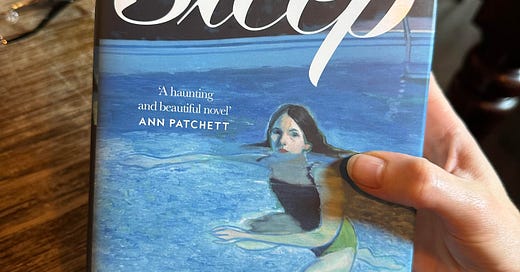

Agree, and it feels very intentional. That blackberry bush is the last place she felt innocent, and clean. On the book jacket, a woman is treading water in a swimming pool. Margaret herself is suspended in this liminal place where she can’t get any proper distance from her trauma, she can’t resolve what happened that terrible summer, because her entire family refuse to acknowledge what happened. At the same time, it’s this very droll book about a woman who CBA with her lame ex and her spiteful, controlling mother. This part on her ex-husband, Ezra’s job, at a magazine called The Really, really made me lol:

“In his seven-year tenure, the magazine had cycled through many names: Ikon, Aria, Interrobang. He seemed to spend most of his time in meetings brainstorming new names, or in meetings about best practises for future meetings for brainstorming new names, or in meetings to discuss the demographics of those future meetings and how to ensure that everyone participated equally in the important work of brainstorming new names. Occasionally he worked on an infographic about disinformation.”

Interrobang.

I want to talk about the ex-husband stuff because I just love the direction Jones went with that relationship. I’ve seldom read a female divorced character be so unbothered and unrepentant about her decision to divorce a man who was, to the rest of the world, a perfectly great choice.

He’s obsessed with being seen as a ‘nice guy’, which means he’s not all that nice to his wife. When Margaret gives birth, he won’t let her go to the hospital until she literally can’t stand, because he doesn’t want to be seen as a bother to the hospital.

I officially hated Ezra when we learn that she had confided in him years ago, only for him to never bring it up and then completely dismiss it when he does. What a jerk. He’s a “fake nice” guy. I enjoyed her relationship with Duncan, too. I love that scene at the end when she does tell him what happened to her and he’s “the right amount of angry.” I think that was very validating for her. Their relationship is so sexy and freeing and really gave us a window into a different side of her. She was mother, daughter, sister, wife—and all woman. It was really fun. I kept expecting something to happen with her childhood friend though, the brother I mean. I felt like that was a bit of a romantic red herring.

This is definitely a moment in a woman’s life where she is breaking free. Her new relationship with her boyfriend Duncan is freeing but also painful: she struggles to trust his teenage sons, which obviously hurts Duncan enormously, because she herself was violated by a teenage boy and no-one did anything about it. In fact, her mother has punished her ever since for making her look at something she didn’t want to look at.

I also found the exploration of mothering incredibly well done here—that juxtaposition between how she mothers, and how her own mother mothered her. I went back and forth a lot in the book wondering if the mother knew. At the end, I figured she must have known something. And then, like you said, the difference in how she and Margaret deal with their trauma in relation to their children. One shields them, and the other willingly exposes them — in fact, weaponises them. It was horrific to watch.

I agree, the book is a fascinating exploration of learning how to mother, how you want to mother, when you were effectively motherless, raised by a mother who made your entire childhood about your father’s infidelity. And oh yeah, her mother knew. She just didn’t want to be made to look. Margaret tells her about the camera Neal hid in the bathroom. And then again, after her mother upbraids her for being ‘a bitch’ to her brother, Margaret says very clearly, you know why I hate Neal.

I remember in that initial camera scene, Margaret is looking at her mom and thinking that she was silently begging her not to make her have to look. Deciding to be ignorant. Deciding not to force her to confront her son. And that later scene when Margaret says, “you know why,” really broke my heart because it meant her mother had chosen, year after year, to let Margaret carry that trauma alone all this time.

I agree—agony to read. Exquisitely well done, though.

What did you think about Neal as a character?

Neal was vile. A total farce. The way he ‘disciplines’ his 6-year-old when he asks for more cake, coming short of actual physical violence, it’s like this indefinable abuse. Margaret observes that if Neal had hit his son, they’d all be able to say, that was wrong, and then she’d be able to say look, this is a bad man. I told you he was a bad man! But because he does this horrible sort of military hold on him, and makes a spectacle of him, where the boy sobs himself into a terrified stupor, it’s ignored.

I’ve said that the book felt dreamlike, but it also felt quite insidious in how it presented these small, unnameable infractions that were not small at all, while holding up a mirror to our societal hypocrisy—because as long as things are not all bad, then we can feel justified when we do nothing.

This is something that you see throughout the book: this idea that because something is not crystal clear in its badness, that people will just ignore it. It kind of feels like a comment on how binary contemporary life has become. How things are seen as good or bad with no shades in between.

Yes, the author really takes pains to explore how dubious binaries can be. Even with her relationship with Ezra, people could not understand how she could leave him because he wasn’t doing anything “bad.”

Everyone refuses to accept that she wants to leave Ezra. Especially Ezra. Jones is so funny on Ezra’s kind of ostentatious woundedness. At one point he sends her this link to an article about ‘restorative justice’ and she texts him back, ‘I’m not the apartheid government of South Africa'!’

Remember that scene where Margaret meets Ezra’s new girlfriend for the first time? She had been picturing her as this slightly less hot version of her? And when she finds out his new girlfriend is hotter and younger, she does this thing where she asks herself, Am I jealous? But then immediately goes, Actually, no I’m not. I quite like her, she’s okay. I thought that was gold. She was truly so over Ezra. Zero qualms.

Oh my god, yes, I loved the scene when she meets Anaya—who Margaret observes uses coloured gel pens to write elaborate lists of meals she wants to cook. (Scathing!) Anaya tells Margaret that she is helping Ezra with ‘his trauma’. I am Ezra’s trauma, thinks Margaret. And this is what I love about Jones’s writing, about the depth of it, because this isn’t just some droll observation about how Ezra thinks Margaret has wrecked his life, it’s an example of how lucky Ezra is, for his worst trauma to be his wife leaving him—rather than sibling abuse. We see that in her role as an editor on a magazine during the apex of MeToo, as well. I thought this passage was exquisitely well put:

“She didn’t want [her daughters] to know about Harvey Weinstein. Not yet. But if she was going to pick an introductory predator, a sort of textbook example, he was a good choice… It was reassuring how much he looked like an actual A-list demon. His awfulness was so predictable, so easy to imagine, it didn’t frighten her. [But] how could she prepare her children for the awfulness that couldn’t be imagined? How could she prepare them without ruining their lives? Ezra, their father, wouldn’t help. He had no experience of such things; she was the worst thing that had ever happened to him.”

Funny, the more we talk about it, the more I realize how smart this book really was. I so enjoyed that scene of her picking and choosing what stories got to be told, and her thought process in doing that. It’s both so pointed and arbitrary at the same time.

I found her work as an editor of these particular stories super interesting. Several times, Margaret makes off-colour comments about the women coming forward with their stories of abuse. For instance, she tells a horrified colleague that when she hears the word ‘survivor’ she thinks of Destiny Child. But for her, Weinstein is an obvious bogey man. There is no ambiguity, everyone knows he is bad. She can’t help but think of her own abuse, which is so taboo, that no-one will admit it. I think that’s a really brave thing to write about, and to write about with such thought and nuance, which says something about the complexity of sexual trauma, especially that which has been buried. “How thin, was the line between normalcy and horror”—I think that’s the best line of the book.

I’ll be honest, when I first read this book I wasn’t sure how much I enjoyed it. Usually I appreciate spare narratives, but I guess at the moment I read it, I wanted something more plotty. I wasn’t even sure how much we’d have to talk about.

Ochuko! I could go all night long on this book. I loved it for what it said about motherhood, marriage, divorce, sex, journalism, America, trauma, the male ego—each theme was as explored as well as the last. I really, really rate it.

Loving these fireside-esq chats so so much. Are there really only 5? coin, dream count, perfection, gunk, and sleep? I want to read the exchange between you too on every book. 🥹

Loved this - have immediately requested Sleep from my library! Thank you for sharing